- Stat Significant

- Posts

- What's the Greatest Year in Oscar History? A Statistical Analysis

What's the Greatest Year in Oscar History? A Statistical Analysis

What was the best year for Hollywood's biggest night?

Titanic (1997). Credit: Paramount Pictures.

Intro: The Oscars’ Never-ending Decline

No matter what The Oscars do, they always seem to disappoint. Sometimes, the Academy Awards are too commercial, honoring crowd-pleasers like Crash and Greenbook—movies derided by critics as unworthy of prestige. Sometimes, The Oscars are too artsy-fartsy, celebrating films like The Artist and The Hurt Locker—works unappealing to mainstream moviegoers. And sometimes, The Oscars become a spectacle onto themselves, generating buzz and controversy utterly unrelated to the film industry, like Will Smith's "The Slap" and John Travolta's epic butchering of Idina Menzel's name.

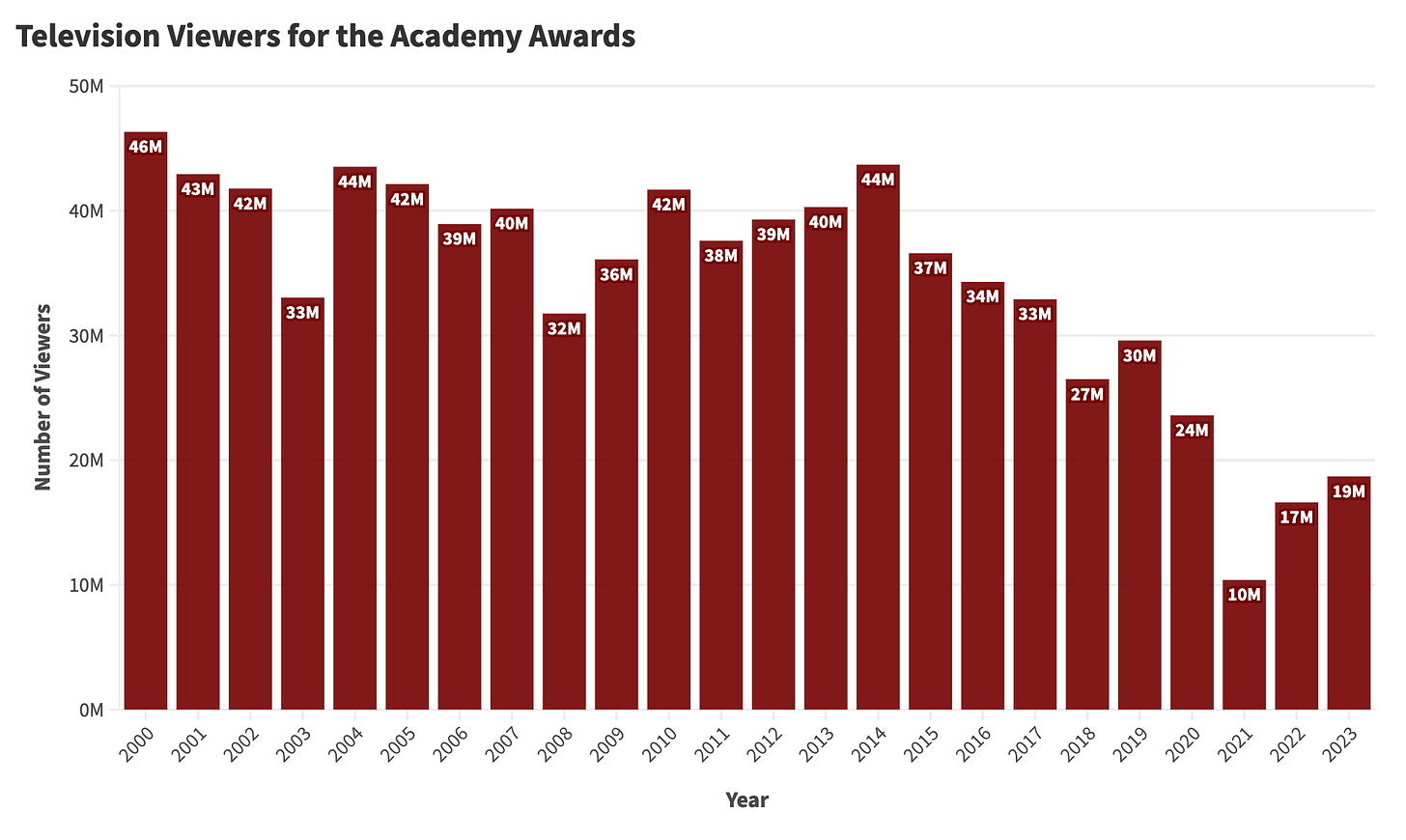

The Oscars' stated purpose is to showcase Hollywood's finest offerings. Unfortunately, how the Academy and its voting blocs define "finest" is ever-shifting, with voters continually recalibrating their choices based on insular groupthink, social signaling, and sociopolitical machinations. Meanwhile, Oscar viewership has steadily declined over the last decade. Each year people care a little bit less about cinema's biggest night.

Media coverage of The Oscars consistently highlights the ceremony's declining relevance, with headlines like "Are The Academy Awards Losing Their Relevance?" and "Latest Oscar News Proves Awards Shows Are Irrelevant." At some point in the last ten years, a prevailing consensus emerged regarding the ceremony's obsolescence, framing the awards as a once-prestigious institution whose best days have long passed. According to this narrative, The Oscars once stood as a reflection of popular culture and artistic excellence, and, over time, Hollywood and its biggest night have gone astray. So today, we'll evaluate ninty-five years of Academy history to understand when The Oscars thrived as well as the periods that appealed to various demographics.

To assess the quality of different Oscar years, we'll employ a diverse set of perspectives, highlighting memorable nominees based on the selections of various groups, including:

Rankings from online databases: the people's choice.

"Best of" lists from movie critics: the intelligentsia's choice.

Box office success: the choices of The Invisible Hand.

We'll deconstruct the preferences of each constituency before pinpointing a consensus selection. Perhaps we'll find that The Oscars’ best days are over. Maybe we'll see that each decade simply has highs and lows—that the show has experienced no discernible rise or fall. Or possibly, like The Oscars themselves, everyone will be mildly disappointed with the output of this analysis, no matter the conclusion.

Online Movie Rankings: The People's Choice

Parasite (2019). Credit: CJ Entertainment.

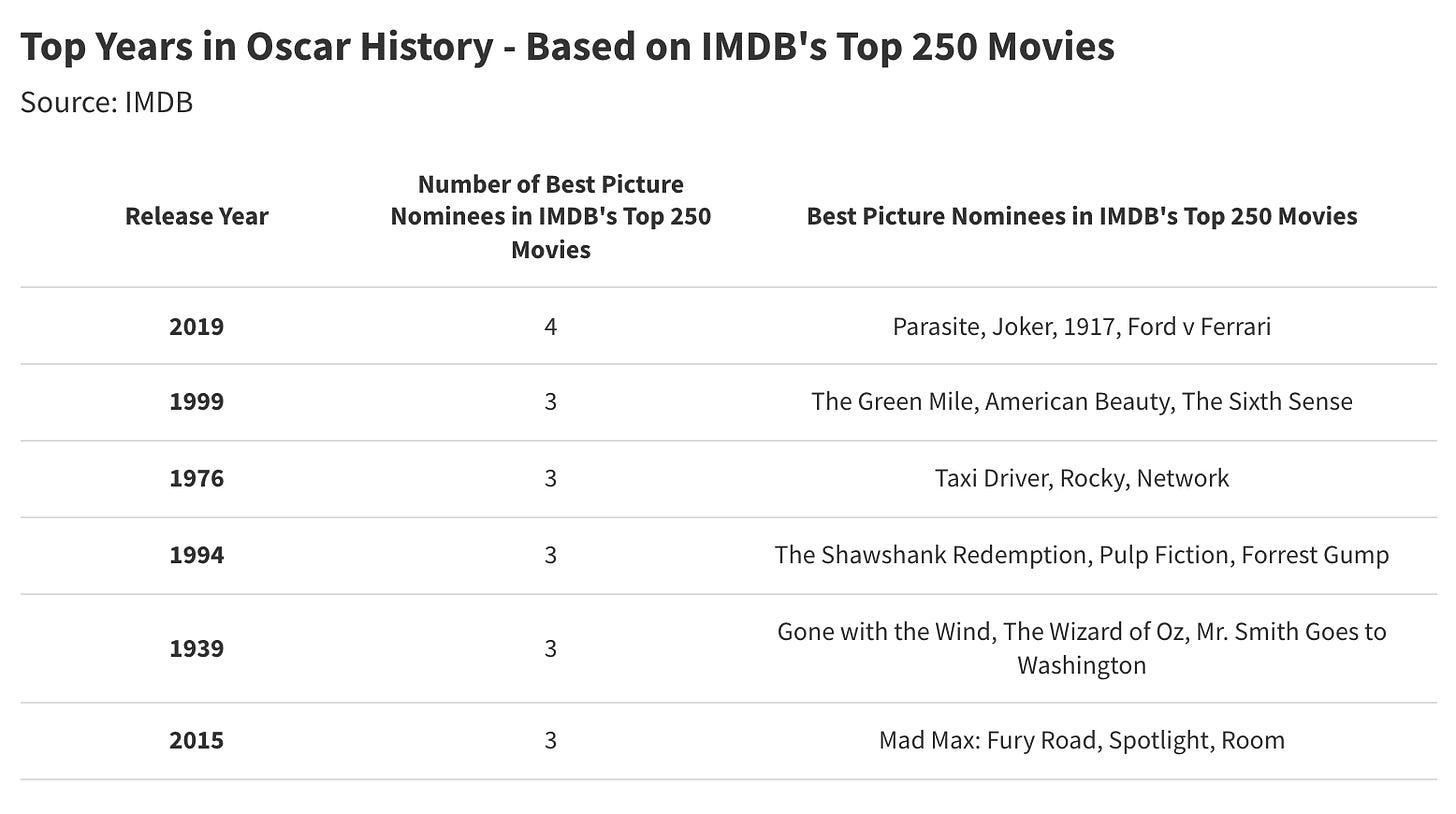

The Internet Movie Database (IMDB) presents a unique intersection of moviegoer taste and large-scale data capture. Users express viewing preferences as free-form text reviews and star ratings, and the platform parses, catalogs, and aggregates this user-generated content to facilitate movie discovery. Through IMDB's massive dataset of consumer preference, we can discern a movie's long-term legacy absent Hollywood marketing campaigns and highfalutin critic reviews. We'll analyze the overlap between Best Picture nominees and IMDB's top 250 movies to understand how Oscar selections compare to online consensus.

Examining our overlapping films, we find a high concentration of movie selections at the turn of the century and the late 2010s. IMDB's nascency (relative to film history) heavily influences this distribution, as the platform has only existed since 1990.

At the same time, our list of years with the most significant overlap showcases a variety of eras.

Each year on this list can be traced to a distinct era in cinema history. 1939, whose nominees are highlighted by Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, encapsulates the high point of “Old Hollywood”—a time when the studio system reigned supreme. 1976, whose Best Picture candidates include Rocky, Network, and Taxi Driver, represents the peak of "New Hollywood"—a period driven by auteur filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet, and Steven Spielberg, who deviated from the traditional studio mold. 1994 and 1999 were illustrious years within a 90s landscape that saw an explosion of indie films, like Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction, and a plethora of highbrow, high-budget adult-oriented prestige pictures released by mainstream studios like The Green Mile, American Beauty, and The Shawshank Redemption.

Want to Chat About Data?

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with stats work or research? Reach out if you want to discuss a data project or potential collaboration.

Critics' Choice: Fuel for the Intelligentsia

The Godfather Part II (1974). Credit: Paramount Pictures.

Film critics typically serve two distinct functions: appraising recent releases and curating a distinguished selection of film classics.

The role of the film critic has changed since the days of Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, as pundit influence over film box office has waned. There is a high probability that Gen Z best understands film criticism as the input to a Rotten Tomatoes score. At the same time, film critics still command cultural influence through curation, identifying titles of outstanding artistic merit and documenting these films for posterity.

Google "Best films of all time," and you'll find a myriad of publications pushing similar incarnations of the same rankings. For our purposes, we'll focus on three recent lists of above-average prestige:

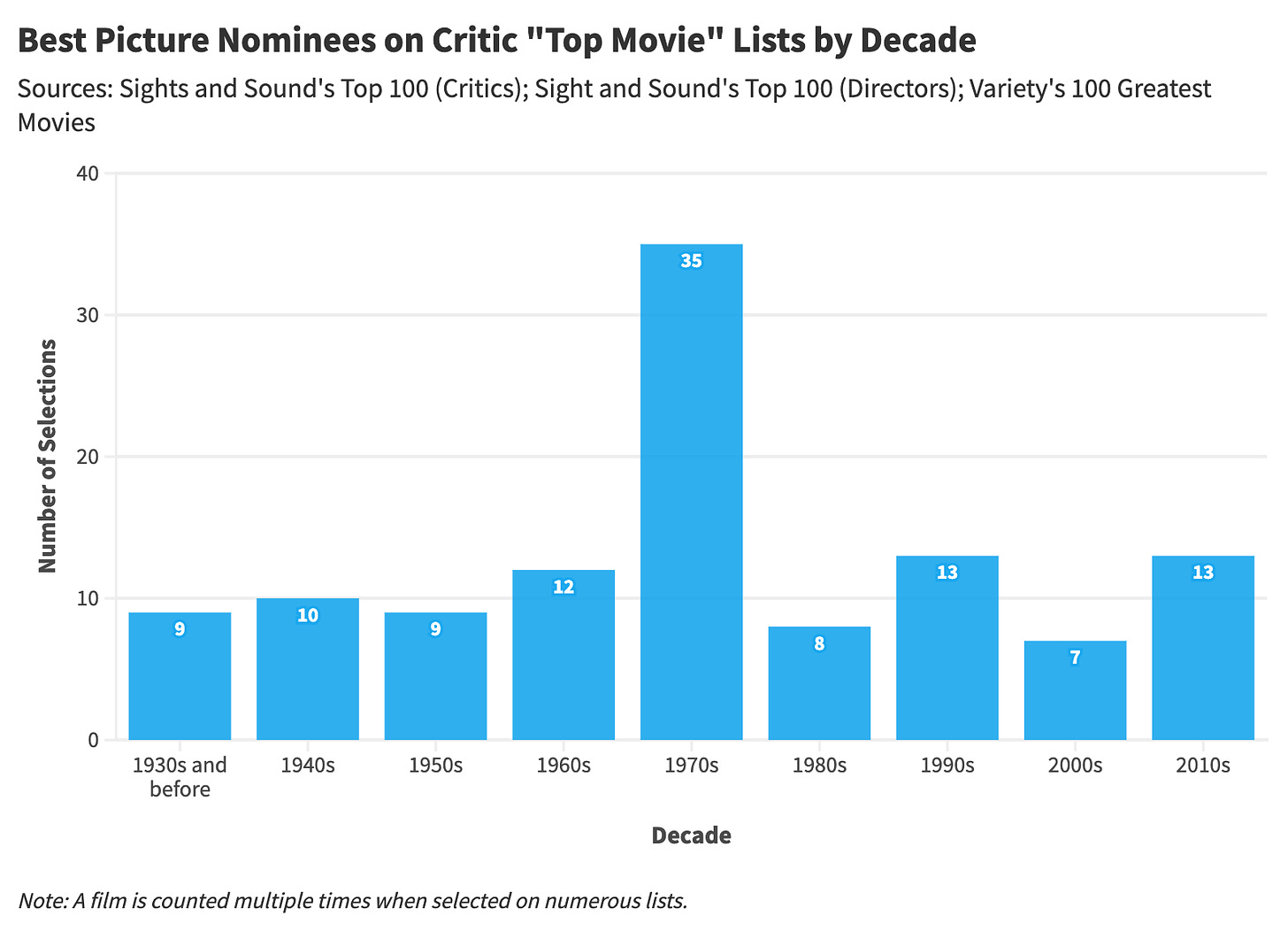

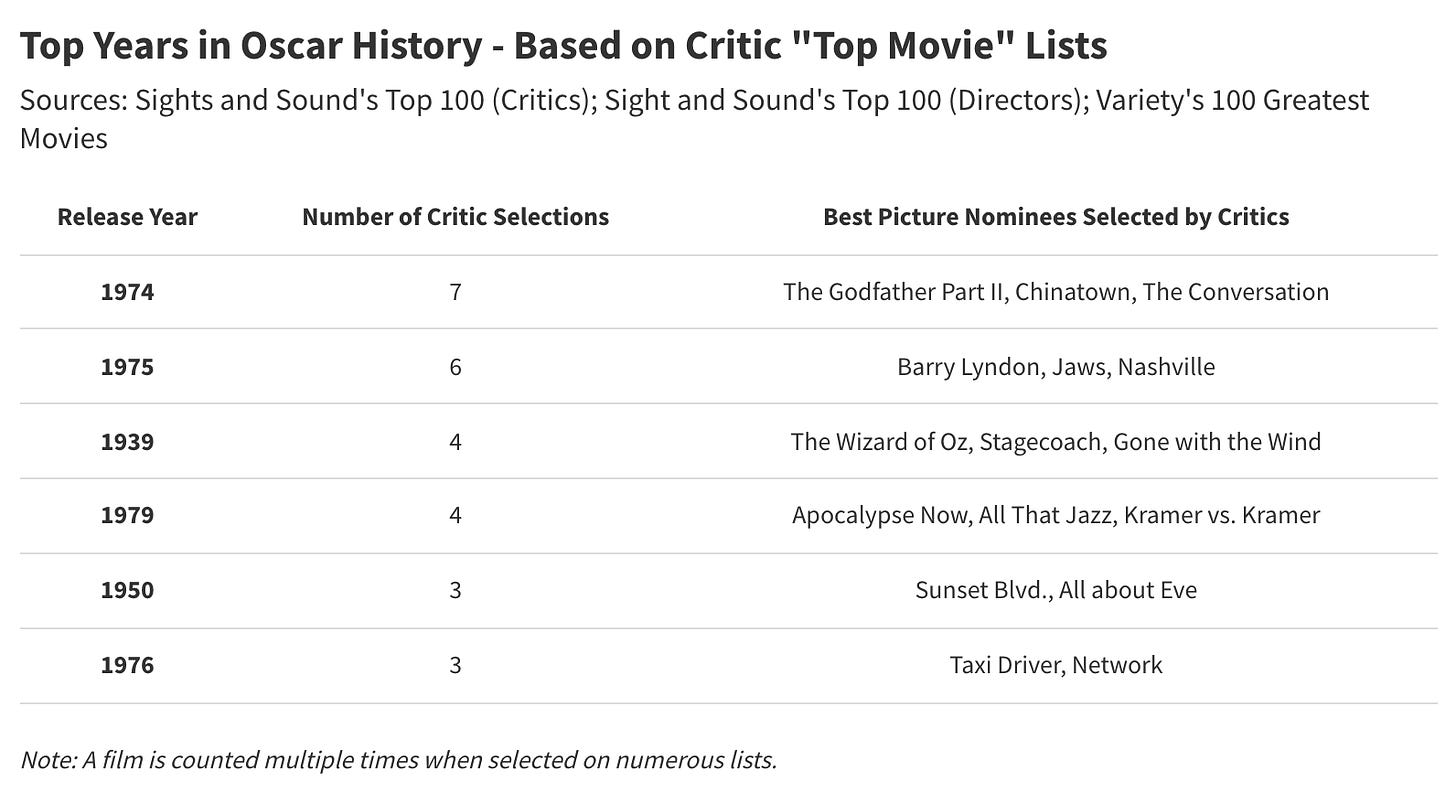

Reviewing the overlap between Best Picture nominees and critic “Top Movie” lists reveals a preponderance of titles from the 1970s.

The mid-1970s saw a cavalcade of auteur-driven masterpieces, including Coppola's Godfather Part II and The Conversation (released in the same year), Roman Polanski's Chinatown, Spielberg's Jaws, Robert Altman's Nashville, and Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon. Critics often fixate on the visionary directors of "New Hollywood," a group of filmmakers who famously broke free of studio control to reinvigorate American cinema. There is an intense nostalgia for this period—an era when creative and commercial interests briefly aligned to provide imaginative artists with ample funding. Ultimately, the 1980s would replace director-centric projects with studio-driven big-budget blockbusters (Top Gun, Beverly Hills Cops, Die Hard, etc.)—movies purposefully crafted for outsized returns.

Separately, 1939 also makes this list, elevated by two undeniable classics in The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. These films have demonstrated remarkable longevity, given so many elements of their production could now be considered anachronistic.

The Box Office's Choice: The Dollar Decides

Gone with the Wind (1939). Credit: MGM.

The immediate reward for making a good movie is money (pretty profound, I know). The Oscars supplement this economic incentive by rewarding films in the form of prestige. At the same time, the Academy Awards make money by garnering the largest possible television audience, which leaves them forever walking a tightrope between honoring commercially successful blockbusters and artistically inclined pictures. If too many high-grossing films are nominated, then the show is not highlighting underrepresented work. If too few commercial works are nominated, then The Oscars are accused of elitistism, heavily disconnected from the tastes of everyday moviegoers.

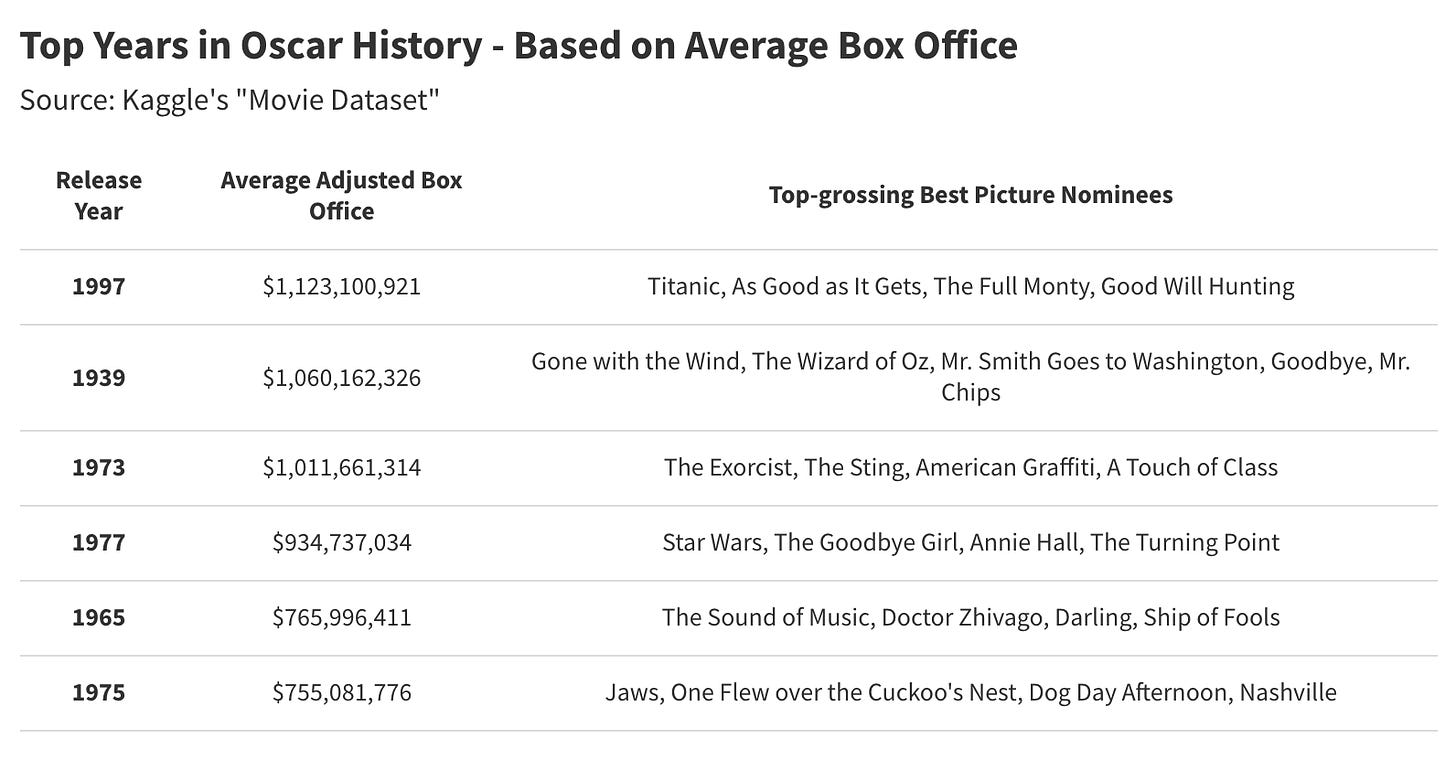

We'll use the average adjusted box office amongst a given year's nominees to evaluate commercial success for Best Picture contenders. It's important to note the primacy of outliers in this analysis. In assessing Oscar nominees by average gross, we index heavily on mega-earning blockbusters like Titanic and Gone with the Wind, which racked in billions while winning Best Picture. We want to highlight years in which The Oscars recognized works of impeccable mainstream success, instances where widespread popularity and Oscar pedigree converged.

When looking at the decades with the highest average gross amongst Oscar nominees, we see upticks in commercial success in the 1970s and 1990s.

The 1970s brought us the modern blockbuster in the form of Jaws, Star Wars, and The Godfather, all films that captured Best Picture nominations and Oscar recognition. The 1990s saw global box office smashes like Titanic, Forrest Gump, and Beauty and the Beast garner global box office acclaim in addition to Academy nods.

Our Oscar years with exceptional commercial success are usually driven by one or two blockbuster hits.

1997 has Titanic, 1939 has Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, 1977 has Star Wars, and 1975 has Jaws. Most of the nominees from these years performed exceptionally well at the box office, regularly clearing $200M in adjusted gross. Still, this ranking is mainly defined by outliers—as are studio bottom lines.

And Our Consensus Selection Is...

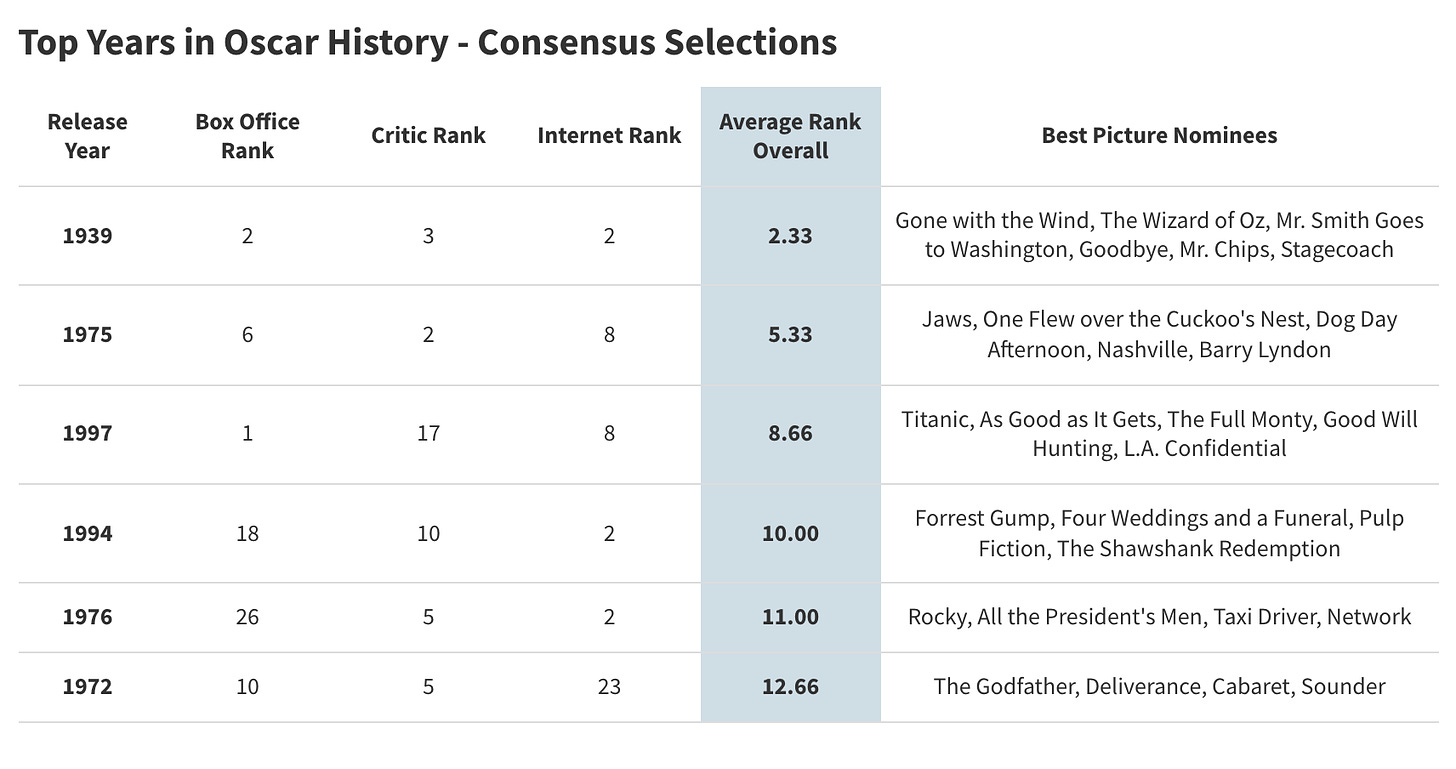

Merging our three datasets and calculating the average rank for each year across these groups, we find 1939 to be our consensus choice, beating out a handful of nominees from the 1970s and 1990s.

1939, the 1970s, and the 1990s were periods where commercial, artistic, and critical incentives aligned, marked by Hollywood classics produced by the studio system, new Hollywood, and the growing global film market of the 1990s.

It's important to note that these years fall within discrete eras twenty or thirty years apart. There is no one period where cinema's finest were best recognized by the Academy Awards, but rather a few periods. Said differently, The Oscars and Hollywood have experienced ebbs and flows. Maybe the 2030s will see a revival in the film industry, producing an influx of Oscar nominees that stand the test of time.

Final Thoughts: An Ever-Failing Balancing Act

Sally Fields’ 1985 Oscar Speech. Credit: ABC.

Broadly speaking, The Oscars cater to three distinct demographics—entertainment professionals, cinephiles, and mainstream audiences. Actors, directors, cinematographers, and other industry workers care about the awards for what they say about value in their industry—what works receive prestige and whether that prestige can be converted into career capital. Movie lovers care about the purity of cinematic superlatives—whether films worthy of awards are produced and whether these "worthy" films are honored by award shows. The Oscars’ third demographic is pretty much 99% of the population—people with no inherent interest or connection to The Oscars. In theory, the Academy Awards are meant to represent industry professionals and cinephiles, but their perceived success is heavily dictated by this last 99% of humans.

At a certain point, The Oscars became an entertainment product, judged on their ratings and their ability to amuse the masses. As such, the Academy is constantly juggling the needs of mainstream moviegoers, Oscarphiles, and its voting base, reacting to backlash, over-correcting, and then correcting for these over-corrections. The result of this twelve-dimensional calculus is a product mildly dissatisfying to all constituencies.

Like Saturday Night Live, there is a perception that the Academy Awards are in a perpetual state of decline. According to this logic, The Oscars meant something when we were younger, and now they're a farce. But what if The Oscars never made sense? What if they've always been a farce?

In 1948, The Atlantic published a dispatch from famed novelist Raymond Chandler on the author's experience at that year's Academy Awards, an essay where Chandler ruthlessly highlights the show’s unabashed absurdity and self-aggrandizement. On the voting process and inter-industry politics, Chandler quipped:

"It is against this background of success-worship that the voting is done, with the incidental music supplied by a stream of advertising in the trade papers (which even intelligent people read in Hollywood) designed to put all other pictures than those advertised out of your head at balloting time. The psychological effect is very great on minds conditioned to thinking of merit solely in terms of box office and ballyhoo."

Chandler then dissects Hollywood's use of The Oscars for self-mythologizing:

"To those who know Hollywood, all that went on was the secure knowledge and awareness that the Oscars exist for and by Hollywood, their purpose is to maintain the supremacy of Hollywood, their standards and problems are the standards and problems of Hollywood, and their phoniness is the phoniness of Hollywood

Perhaps The Oscars never made sense, doomed by the subjective act of evaluating art and then commodifying that process as a bastion of prestige. Maybe their premise and presentation have always been absurd—a popularity contest dressed up as a cultural event of the utmost sophistication.

At the same time, there is an intangible staying power to this dressed-up popularity contest. Much like high school, acknowledging popularity's pointlessness is still an acknowledgment of that thing's existence. When people write take-downs of the Academy Awards or tweet about its obscurity, they're justifying the show's significance by way of recognition. Nobody cares about the SAG awards, DGA awards, Producers Guild awards, or Golden Globes—as such, nobody thinks to critique these shows. The Oscars justify outrage, which is better than indifference, and their network effects are strong enough to support an entire class of movies we deem as "Oscar-bait," like The Holdovers, Poor Things, Maestro, and 50% of A24 films. If The Oscars die, so does a mini-economy of artistically-minded projects.

The Oscars are flawed for so many reasons, but they still sit near the center of our culture, whether you love them or love to hate them. Perhaps one day, everyone will lose interest in the Academy Awards and simply stop talking about them, but today is not that day.

So, if you're at an Oscar party and you're discussing the show's cultural relevance, you can tell your friends the ceremony peaked in 1939, and you can show them the data to back it up.

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]