- Stat Significant

- Posts

- What Captures Our Attention in an Algorithmic Age? A Statistical Analysis

What Captures Our Attention in an Algorithmic Age? A Statistical Analysis

The cultural icons and creative works that dominate attention in the 21st century.

Squid Game (2022). Credit: Netflix

Intro: What is the Zeitgeist in 2025?

In 1998, movie theaters noticed an inexplicable phenomenon surrounding the release of Meet Joe Black, a forgettable drama starring Brad Pitt and Anthony Hopkins. While the film itself was nothing special, moviegoer behavior was cultish and bizarre. A few minutes into the movie, many audience members simply got up and left the theater, with this confounding trend playing out in cinemas nationwide.

Theaters were baffled: Why did consumers purchase a full-price ticket only to leave shortly after the film began? Well, it turns out Meet Joe Black wasn’t the main attraction.

The real draw was the debut trailer for Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace, which played before Meet Joe Black. The Phantom Menace was the first expansion of Star Wars’ cinematic universe in over fifteen years. Fans were so eager to catch a glimpse of George Lucas’ long-awaited prequel that they were willing to pay $15 to see ten minutes of a completely different film.

The premiere of The Phantom Menace was arguably the most feverishly hyped movie opening of the 1990s. Fans waited for hours in lines that wrapped around entire city blocks just for a decent seat (or a ticket). If you’d asked the average person what that month’s biggest cultural event was, nearly everyone would have said “Star Wars.”

Flash forward to today, a time when popular culture is routinely described as “fragmented” or “siloed.” In 2025, identifying a single, unifying cultural touchstone is far more difficult. Two decades of content abundance—filtered through the kaleidoscopic prism of algorithmic personalization—have given rise to a complicated, perhaps unanswerable question: What does the zeitgeist look like in 2025? For better or worse, I decided this was the perfect jumping-off point for an analysis: an attempt to quantify the (ostensibly) unquantifiable.

So today, we’ll explore how collective culture has changed over the past two decades, what dominates the zeitgeist in an age shaped by personalization, and how the notion of event-ization has evolved post-pandemic.

Brain Food, Delivered Daily

Every day, Refind analyzes thousands of articles and sends you the best reads explicitly tailored to your interests—delivered straight to your inbox.

What Captures Our Attention: 2007 vs. 2024

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of this analysis is choosing a metric for cultural relevance. When you consider the various technologies and institutions that have come and gone over the last twenty years—MySpace, Vine, iTunes, Yahoo, BuzzFeed, newspapers, etc.—picking a single marker of popular interest that stays consistent is anything but straightforward. Fortunately, Wikipedia is a steady bastion of internet curiosity in a shifting digital landscape—particularly the site’s annual ranking of its 50 most-visited pages.

Each year, Wikipedia’s editors publish a list of the site’s most frequented pages, offering a snapshot of collective interest during that period. For this analysis, I took eighteen Top 50 reports spanning 2007 to 2024, categorized each page by topic (e.g., movies, music, politics), and examined how the prevalence of these subjects shifted across two distinct periods: 2007-2012 and 2019-2024.

Before running the analysis, I assumed that music and movies would show diminished cultural relevance while television would reign supreme, buoyed by streaming’s ascent.

However, as is tradition, I was wrong. According to Wikipedia traffic, movies, death, and politics have expanded their cultural footprint, while music and television are less prominent in the zeitgeist.

These results defied my expectations and raised two additional questions:

Is Hollywood (Not) Dead?: I’m constantly told that Hollywood is dying (or already dead), so how do movies still dominate cultural attention?

What Has Replaced TV and Music in the Zeitgeist?: If television and music no longer command the same cultural footprint, what has taken their place in popular imagination?

To tackle the second question, I pulled a list of the most-viewed pages from our combined Top 50 dataset (note: an entry can appear twice if it was included in multiple year-end reports). The results were quite telling: in recent memory, arguably no two forces have reshaped global culture more than Donald Trump and the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Whatever your feelings about Donald Trump’s politics, it’s impossible to ignore how omnipresent he’s been since his first campaign in 2015. Political news, as disseminated by [insert your preferred news outlet or a publication you loathe], remains one of the few topics that commands mass attention. Reporting may differ in tone or bias, but the cast of characters and the events themselves dominate the zeitgeist.

Meanwhile, the pandemic marked a clear turning point in how we experience culture—accelerating the rise of remote work, food delivery, streaming, and other technologies that enable consumption without ever leaving home.

In the entertainment world, the pandemic initiated a figurative baton pass from collective, in-person experiences to siloed, algorithm-driven consumption. Theatrical moviegoing was irreparably weakened, while platforms like Netflix and Spotify cemented their dominance in TV and music, respectively.

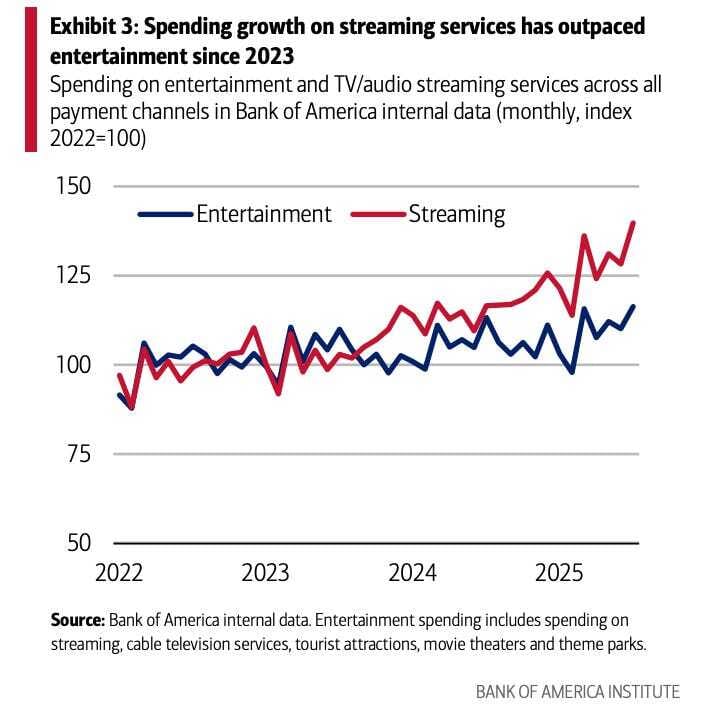

In the past four years, consumer spending on streaming platforms has surpassed combined expenditures on cable TV, movie theaters, tourist attractions, and theme parks.

Source: Fortune and Bank of America.

If TV and music streaming now dominate the entertainment economy, why is the cultural footprint of a single show or musician shrinking? To explore this paradox, we’ll examine the most-viewed TV-related pages in our Wikipedia dataset.

With some notable exceptions, the most heavily trafficked entries cluster around pre-pandemic series with deeply committed fanbases, such as Game of Thrones and Lost.

The television industry once revolved around “appointment viewing,” when a show was so essential that millions tuned in to watch live, with Game of Thrones being the clearest modern example of this phenomenon. Today, outside of live sports and tentpole events like the Oscars, this ritual is largely gone. With endless programming options and on-demand access, viewers rarely watch the same thing at the same time. Post-pandemic, a select group of outliers—like Squid Game and The Last of Us—have proven capable of capturing concentrated global attention.

Now, let’s compare our most-visited TV pages to highly-trafficked movie entries. The film industry is entirely reliant on appointment viewing—persuading audiences to leave their homes and catch a movie during its brief theatrical window. And since the turn of the century, no entertainment property has been more effective at creating collective urgency and hype than superhero films, which dominate our list of most-viewed movie-related Wikipedia pages.

Those who cover the film industry often talk about “event-izing” a movie—turning a release into something so big that audiences feel compelled to leave the comforts of streaming. Intellectual property, such as superheroes and reboots, has proven most adept at generating cultural spectacle and convincing people to spend $20 on a movie ticket. For roughly two decades, Hollywood has been perfecting a formula for must-see entertainment, culminating in Avengers: Endgame, the pinnacle of theatrical appointment viewing.

Now compare this to the music and TV industries, both disrupted by platforms that offer an endless repository of content as mediated by algorithms. With Spotify and Netflix, you’re paying for media abundance. There is so much music and so much television that few shared touchstones exist within these mediums.

Aside from the occasional Taylor Swift release or Netflix’s most-watched show of all time (Squid Game), there is no such thing as an event-ized TV show or album. So, given this content fragmentation, what do people talk about when they get together? Perhaps the weather, maybe some traffic, a new superhero film, and, of course, politics.

Final Thoughts: How Efficient is Too Efficient?

I worked at DoorDash (a food delivery company) from 2016 to 2024, which meant I was there during the pandemic when the startup’s demand surged 3x overnight. Like all businesses, the platform rapidly adapted to changing circumstances, launching a bevy of new features to accommodate unprecedented delivery volume and COVID precautions. Years later, two changes from this period are especially emblematic of a post-pandemic world:

Leaving Food at the Door: Before the pandemic, customers met drivers at the door for a simple, foolproof handoff. But within days of the first lockdown, we launched a new “leave at the door” feature, where drivers would drop off the food and snap a photo as proof of delivery. What began as a health precaution quickly became the preferred method for both customer and driver, who appreciated the time savings afforded by this new ritual—and for drivers, time is literally money. The end result was increased efficiency for customers and couriers, at the expense of face-to-face interaction. The platform became (and remained) a little more impersonal.

Bringing People Back to Work: At some point in late 2021, DoorDash surveyed employees on topics ranging from company connectedness to job satisfaction. At a very high level, respondents expressed concern about “not knowing their coworkers” and “feeling disconnected from the company’s culture,” all symptoms of a remote, geographically distributed workforce. Yet in the same survey, when asked about returning to an office, the answer was just as clear: no thanks. The fix for cultural isolation was too inconvenient, especially for employees who’d grown accustomed to the comforts of working from home.

People saved time and money to the point where shared experience became an inefficiency. This is not because humans are idiots and make the wrong decisions; in fact, quite the opposite. Having experienced these paradigms firsthand, the notion of giving up newfound benefits was hard to fathom.

At the same time, I often worry about humans maximizing for time and efficiency to the point where everyone begins acting like Homo economicus.

For those unfamiliar, Homo economicus is a theoretical figure in economics who always makes perfectly rational, self-interested choices that yield “the best possible outcome.” When given the ability to save time and money, Homo economicus will do that thing—no questions asked.

Homo economicus is hyper-vigilant about the countless trade-offs and hidden “taxes” embedded in every choice. Consider my 2019 decision to see Avengers: Endgame at its midnight premiere, and imagine the litany of “inefficiencies” an overly rational actor might spot in that plan:

Coordinating with friends: 30 minutes wasted.

Buying premium format tickets: $22 that could have been allocated to the S&P 500 or Bitcoin.

Buying a gigantic soda and Cookie Dough Bites: somehow $15, the price of one Chipotle burrito with guacamole (sustenance!).

Leaving your house, getting to the theater early, and hanging out with friends pre-show: 2 hours wasted that could have been spent staring at a computer screen of digital avatars or trading oil futures.

Watching a midnight movie that ended at 3am: decreased productivity the next day, a blow to my personal market capitalization!

Post-pandemic, we’re hyper-aware of the costs we endure for collective experience—the effort required to work alongside others, go to theaters, or watch a TV show at its precise airtime. Sure, many of these newfangled behaviors are rational, especially when it comes to saving money. Yet taken to an extreme, we drift further and further toward a frictionless economical utopia, where shared experience is eradicated in the process (reminiscent of the future depicted in WALL-E).

This leads me to a fun little brain teaser: in this streamlined future devoid of cultural touchstones, what does Homo economicus talk about at the water cooler? This hyper-rational persona cannot discuss a shocking episode of Lost or Game of Thrones that aired last night, a catchy song from a widely consumed album, or a meaningful human interaction they had with their delivery driver. In fact, Homo economicus would not even be at the water cooler—because why leave home in the first place?

Enjoyed the article? Support Stat Significant with a tip!

If you like this essay, you can support Stat Significant through a tip-jar contribution. All posts remain free; this is simply a way to help sustain the publication. You can contribute with:

A One-time Contribution:

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,700 readers? Email [email protected]

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd