- Stat Significant

- Posts

- Unpacking Vinyl's Remarkable Revival: A Statistical Analysis

Unpacking Vinyl's Remarkable Revival: A Statistical Analysis

The fall and rise of vinyl and record stores.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Intro: The Resurrection of "Canned Music"

Vinyl hasn't always served as an emblem of cultural authenticity; in fact, the introduction of the phonographic record was initially met with controversy. Live music advocates like composer John Phillip Sousa warned that phonographs would diminish the value of live performance and discourage people from learning instruments. He famously referred to recorded works as "canned music," arguing that they lacked the personal connection of live performance. Similarly, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) led strikes in the 1930s and 1940s to protest the growing use of recorded music in radio and public spaces.

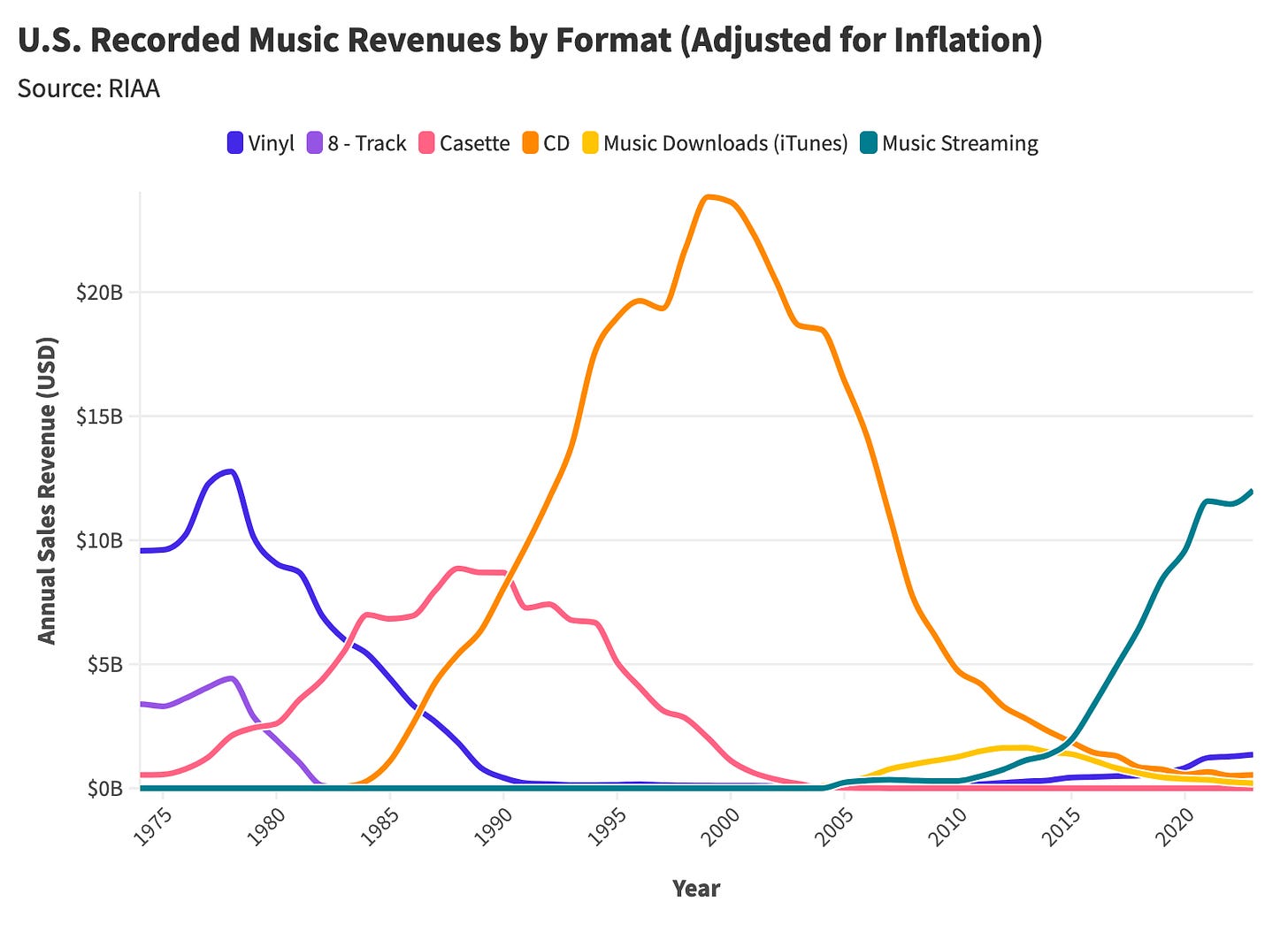

Today, these protestations read as quaint: can you imagine if John Philip Sousa lived to see Spotify or TikTok (or AI-generated music!)? Since the invention of the phonograph, music distribution has been defined by a series of mediums overtaking one another: Vinyl offered a convenient alternative to live performance (or silence) but was later overtaken by cassettes, which were quickly supplanted by CDs, which were eventually displaced by iTunes, which was vanquished by streaming. But then, in the late-2000s, a strange reversal occurred—vinyl sales began to grow, increasing for seventeen straight years. A popular music format several generations (and modalities) removed from its heydey is experiencing a surprising resurgence, Phillip Sousa be damned.

So today, we'll explore the vinyl revival and the unlikely cultural forces animating this format's improbable resurrection. We'll examine vinyl's unique place in a music industry that continually shifts toward convenience and cost efficiency, and reflect on how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the popularity of this once-overlooked medium.

The Fall and Rise of Vinyl

Historically speaking, the half-life of a musical medium is remarkably short. Let's say you were born in the 1950s and enjoy The Who's "Tommy," a rock opera about a blind, pinball-playing prodigy. You would initially purchase this album on vinyl in 1969, replace this record with a cassette sometime in the 1980s, only to then buy "Tommy" on CD in the mid-90s, followed by a purchase of the album on iTunes (to ensure this music was on your iPod), and, finally, you would not buy this album at all, opting to pay $10 a month for the privilege of streaming "Tommy." Who knows how you'll listen to "Pinball Wizard" in the year 2035.

The history of music consumption, as captured by RIAA sales data, is marked by a series of paradigm shifts spanning vinyl's monolithic dominance in the 1970s to streaming's present-day ubiquity.

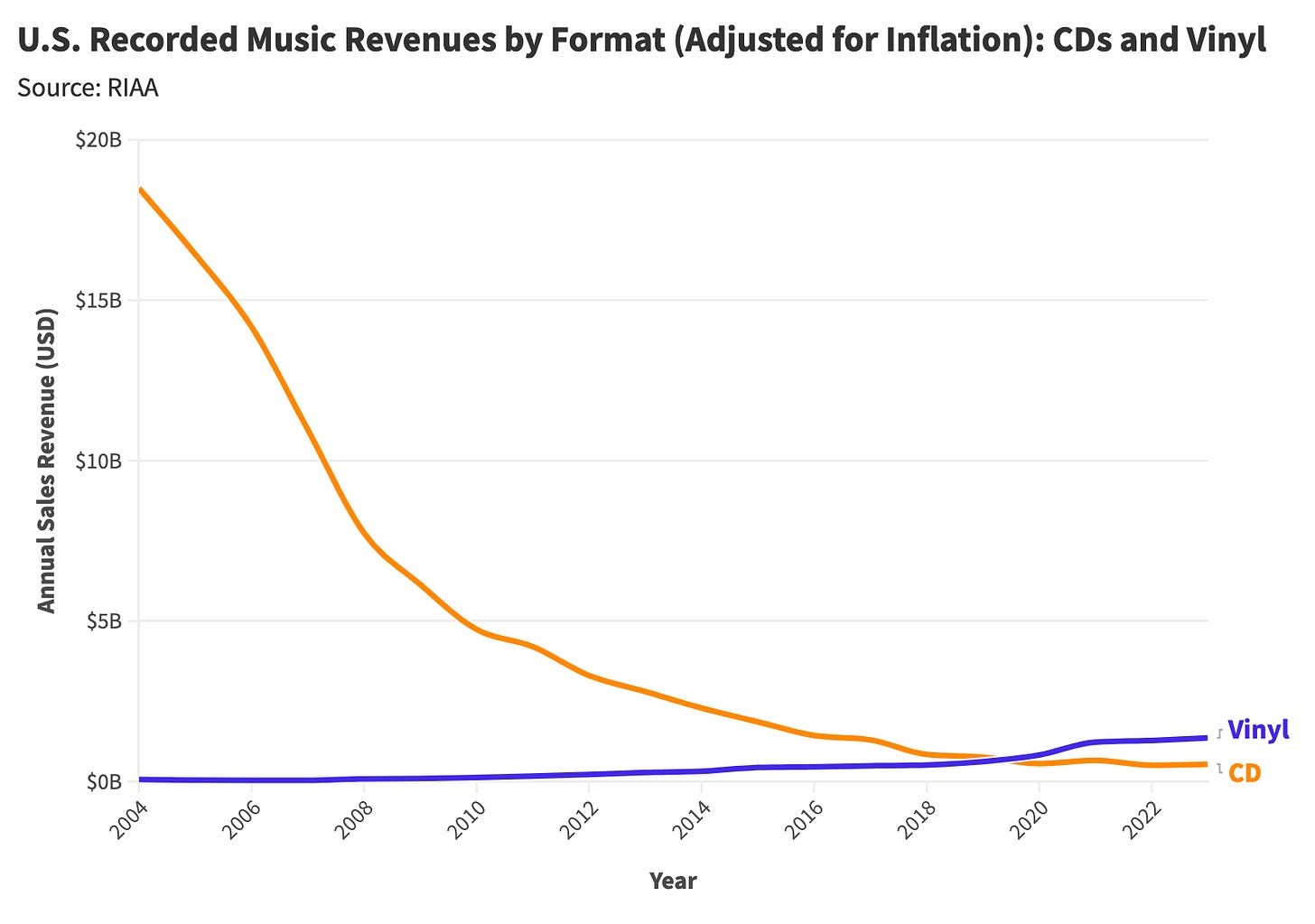

According to this data, record purchases represent a mere fraction of streaming revenues (I hope you didn't come to this essay expecting vinyl to overtake Spotify). But what if we remove streaming and focus on the last two decades? This view offers a different story—one widely reported over the last ten years. Starting in 2009, record sales began increasing while CD revenues continued to fall. In 2020, record sales surpassed CD revenues, outpacing a format that had conquered its predecessor (this being cassettes).

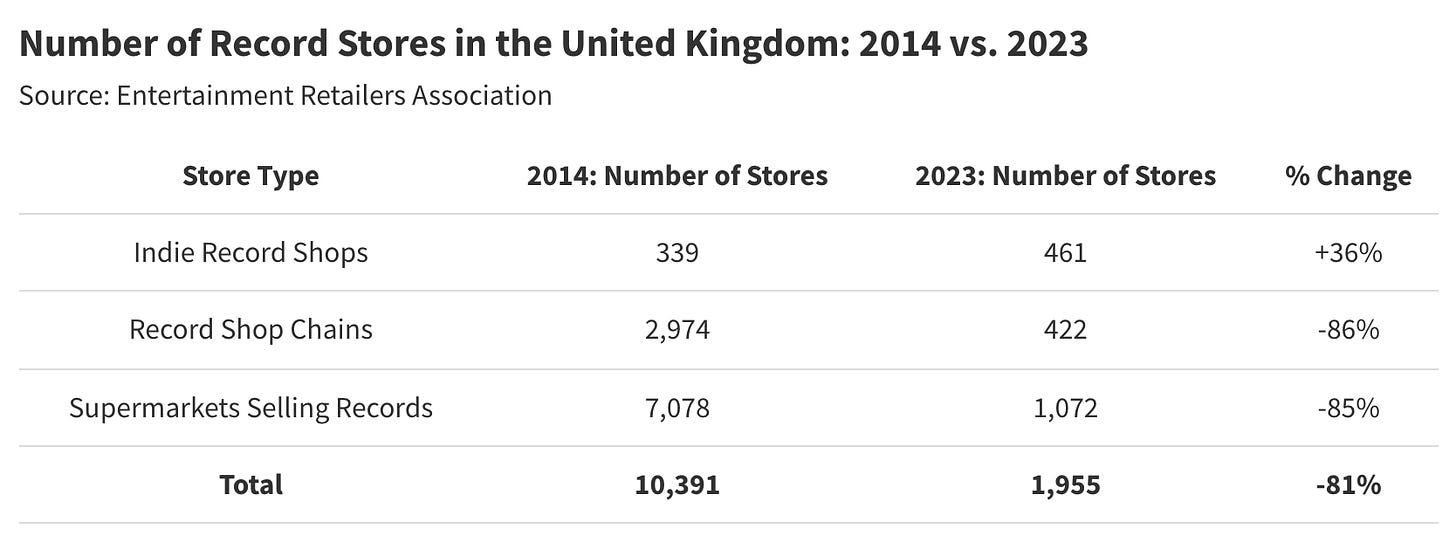

Better yet, a growing appetite for vinyl has sparked a revival of local record stores. Since 2014, the number of stores selling physical media has decreased (because why wouldn't it?), but embedded within this decline lies a pocket of optimism. According to figures from the UK's Entertainment Retailers Association, the number of independent record shops in the United Kingdom has increased while big-box chains like Tower Records have gone bust.

Embedded in this statistic is the experiential appeal of vinyl collecting—to many, the shabby authenticity of a local record shop imbues the purchase with greater meaning. For this cohort, rifling through discount bins and finding a hidden gem outweighs one-click checkout on Amazon.

A resurgence in analog purchasing (no matter the extent) is a surprising development for a music industry that defaults to the most economically rational modality (even if that means buying "Tommy" six different ways). So, what emotional logic underlies a growing affinity for collectorship and material position, and how was this decidedly physical hobby impacted by the pandemic?

Looking For Data Help? Stat Significant Has You Covered!

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data science consulting services!

If you're looking to turn your data into strategic growth, drop me an email at [email protected], connect with me on LinkedIn, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

The Tangible Joys of Record Collecting

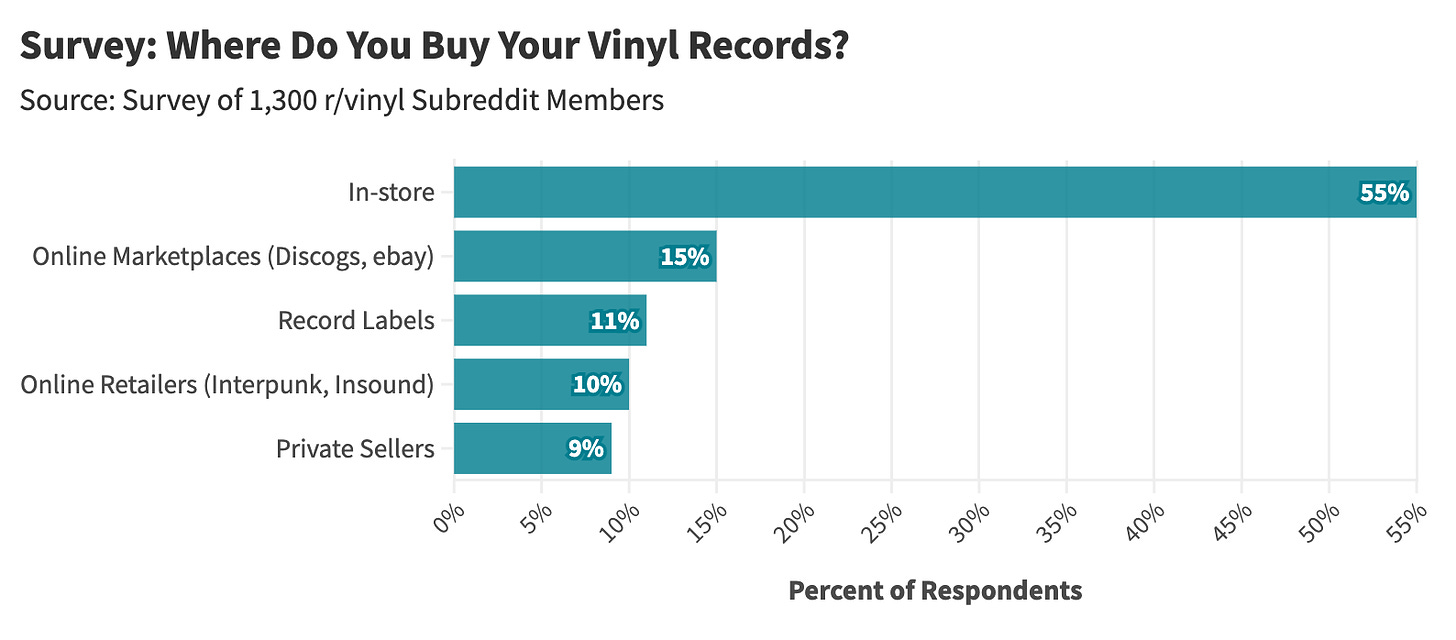

A survey of the r/vinyl subreddit found that most of its users preferred buying records in-store over online marketplaces like Discogs or eBay.

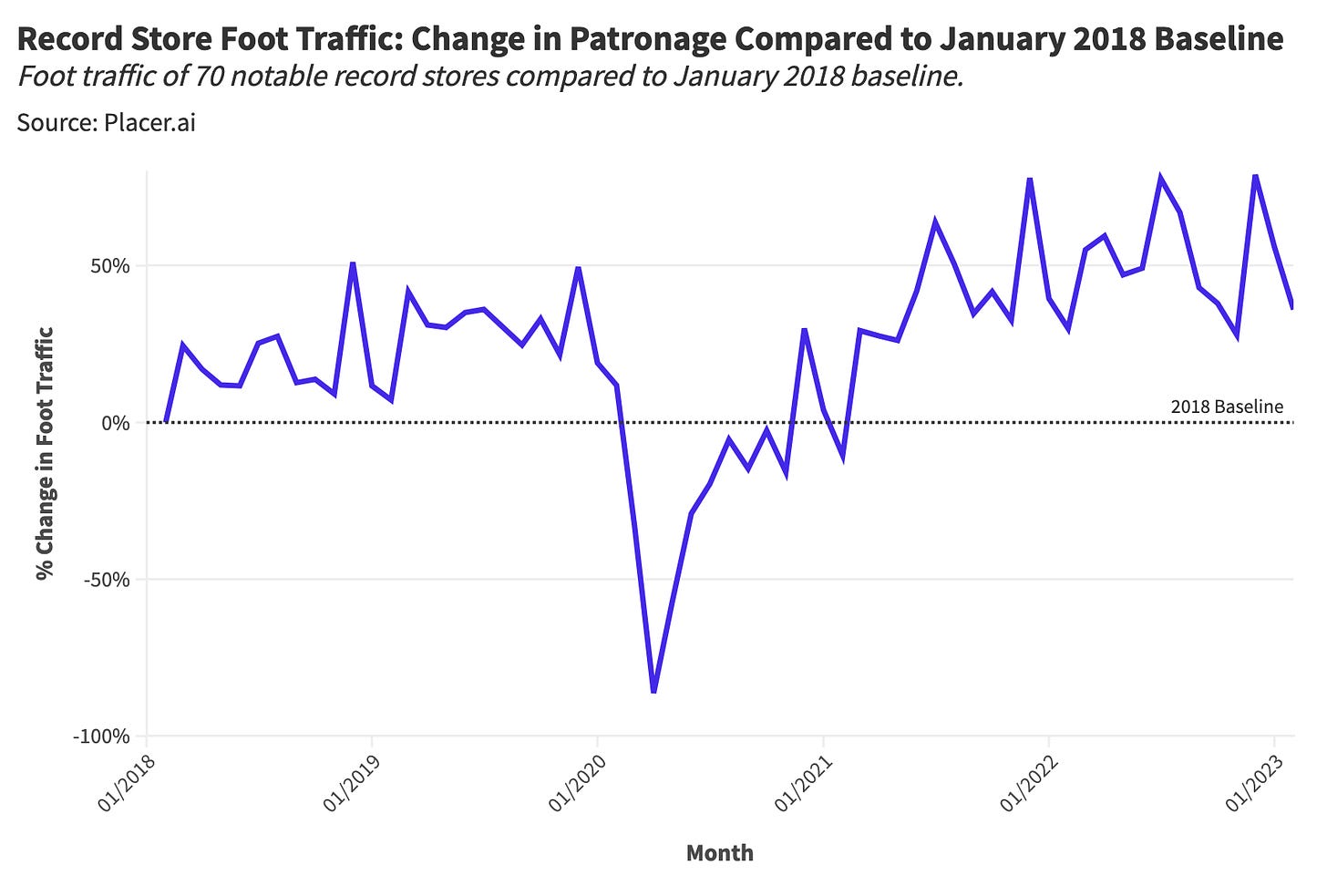

Indeed, the ritual of browsing record stores—of sifting through LPs surrounded by fellow enthusiasts—has increasingly captivated younger generations, even with the convenience of Spotify and Amazon. Surprisingly, the popularity of brick-and-mortar record collecting has grown in the aftermath of the pandemic—a stark contrast to the box office declines that have plagued the film industry over the past five years. According to foot traffic data for 70 prominent record stores, patronage in 2022 and 2023 significantly outpaced visitor figures from 2018 to 2019.

This increase in brick-and-mortar music buying has been interpreted as the confluence of two broad trends:

Frustration with the Growing Immateriality of Culture: It's hard to argue with the appeal of paying $10 a month for unfettered access to virtually every song in human history. Still, you can endorse the convenience and cost-savings of Spotify while accepting that this move toward digital music rentorship has created new problems. If you view music as a core component of your identity, you no longer have a physical totem to express this preference. Your favorite band may be the Talking Heads, but you have nothing to show for this affinity besides their inclusion in a few Apple Music playlists.

A Desire for Physical Connection: Several facets of public life were irreparably altered by the pandemic, which has, in turn, fostered a new set of behaviors to satisfy base needs for social connection and material expression. Personally speaking, I no longer commute to work, my day-to-day subsumed by Zoom and Slack, which means I socialize with significantly fewer people on a daily basis, which means I assign more value to physical experience—of which trips to video and record stores qualify.

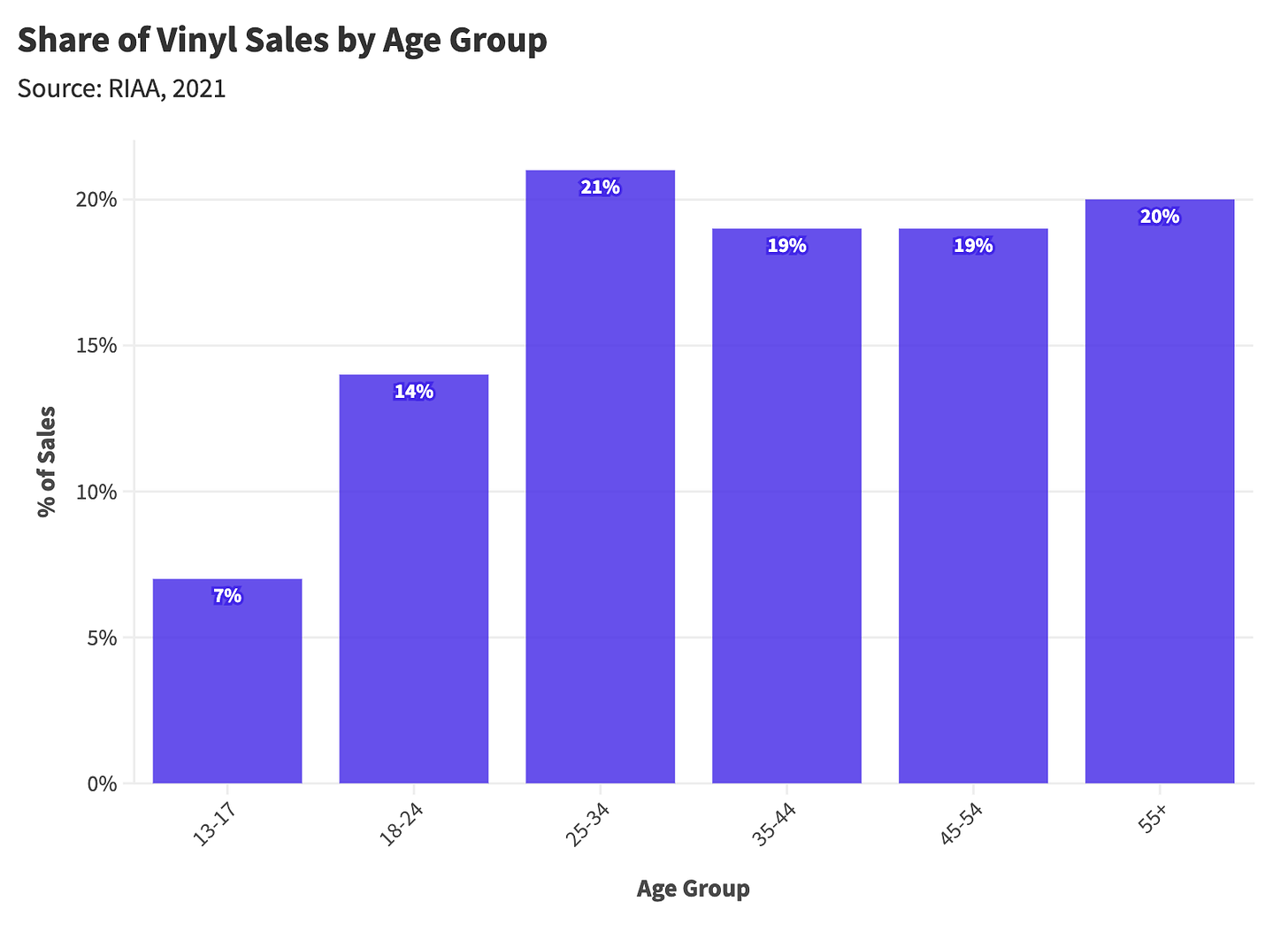

I am in my early 30s—I came of age during the era of CDs and iTunes, two distribution modalities removed from vinyl. And yet the allure of this format—the cover art, the mythic timelessness, the liner notes—feel like the purest form of music consumption (and I can't tell you why). Arguably, the most fascinating aspect of the vinyl resurgence is the demography driving its growth. RIAA data finds record sales to be uniformly split across age groups 25 and above, with surprising sales interest coming from younger generations (below the age of 25).

Taylor Swift's latest album, The Tortured Poets Department, sold 859,000 vinyl records in its first week—setting a new benchmark for the largest vinyl sales week in the modern era. So what compels those not alive during vinyl's heydey to seek out this format?

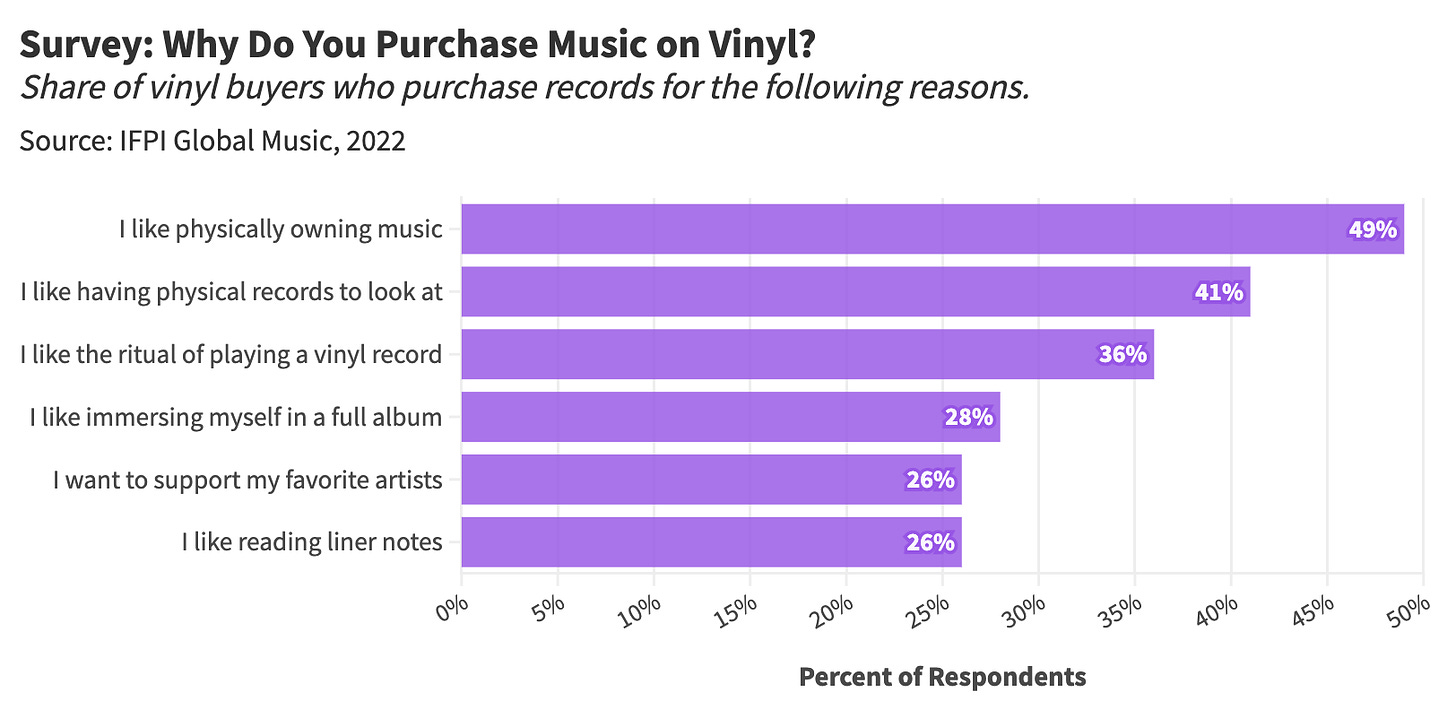

A 2022 survey of 44,000 music consumers found the foremost appeal of record-buying lies in the act of physical ownership. People want to own cultural objects that define them, as opposed to paying Spotify for the privilege of accessing these core aspects of identity.

I feel similarly about DVD collecting, a hobby that brings me joy in spite of economic irrationality. In assembling this collection, I have made a list of my favorite works, vowing to re-watch these films to determine whether these movies are befitting of my hallowed archive. This process has confused my wife because it means I will watch a movie on streaming, enjoy it, buy the 4k DVD, and then proceed not to watch my newly purchased Blu-ray since I just saw the movie. And yet, I love physically owning my favorite films. I often catch myself staring at my beloved discs, ogling their slipcover art like Gollum from Lord of the Rings (I have, at times, with some sense of irony, thought, "my precious" while staring at my collection).

I enjoy owning Blue Velvet and The Departed, verifying my ownership through sight—physical proof that this expression of identity has its place in the material world. The same logic applies to vinyl—physical ownership allows us to possess totems of cultural expression, rendering these affinities tangible.

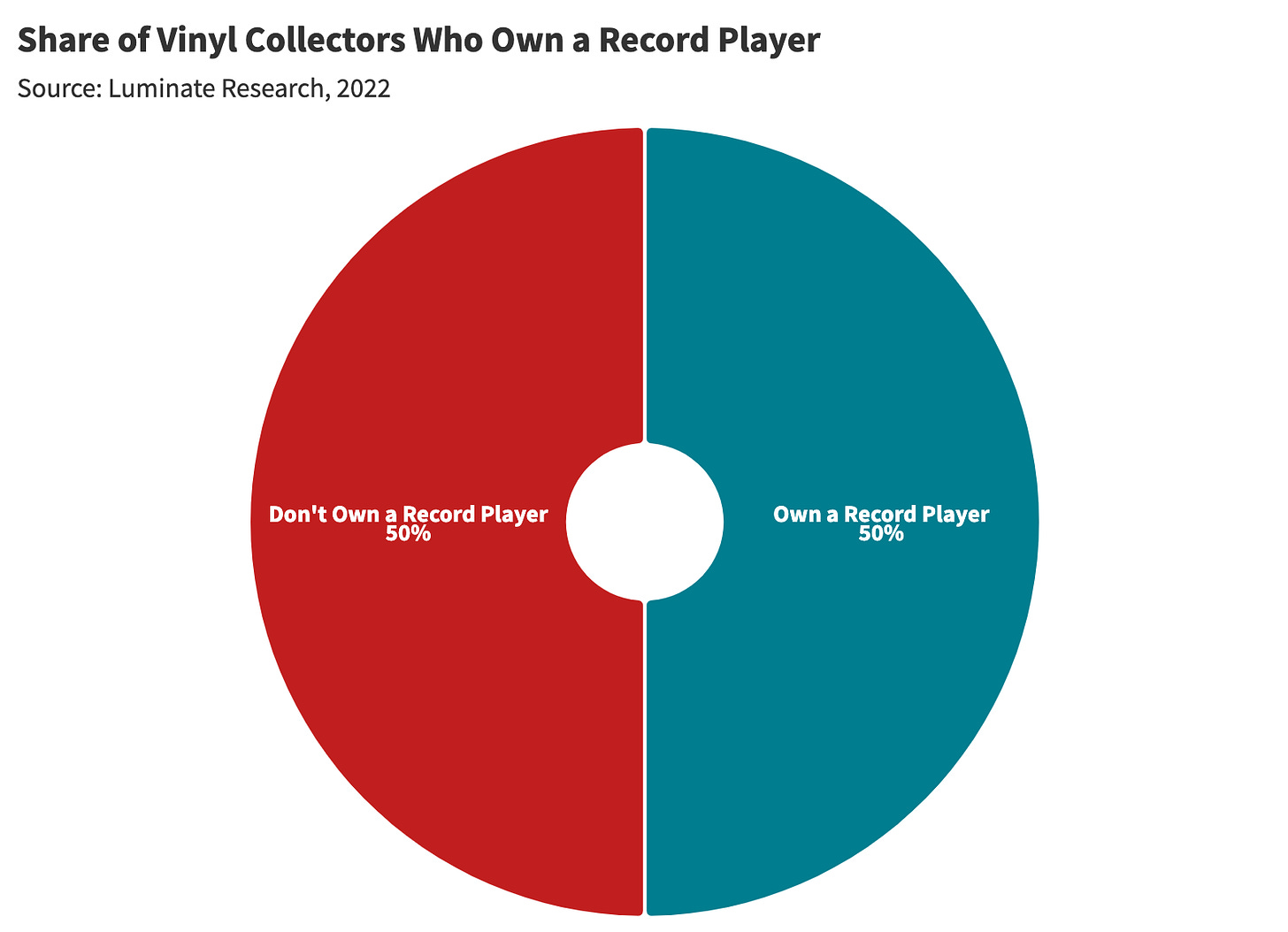

And here is where record-buying gets weird (in a good way): according to research from Luminate, 50% of vinyl buyers don't own a record player. I put together a stupid pie chart to underscore how wild this is.

Naturally, many record collectors purchase vinyl with the intention of playing the album. Still, it's mind-boggling (in a good way) that a majority of purchasers may be acquiring these items agnostic of their initial intent (to play music). For record player-less vinyl collectors, the primary appeal of an LP is the artwork—that this item represents a thing you love—and the acknowledgment that it can play your favorite music (if you so choose). In this sense, the LP is an expression of identity first and a media artifact second.

The vinyl revival is an inevitable adaptation to the increasing intangibility of culture. There is more to consume, and the de facto business model for consumption is subscription-based (renting access to content). For many, however, a profound desire exists for identity, ownership, and permanence—and vinyl uniquely satisfies this instinctive need.

Final Thoughts: Why Not Both?

High Fidelity (2020). Credit: Hulu.

I bought a record player in college because, well, it just felt like a thing to do. In the short term, this was awesome—I physically owned Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band and Californication, which I could show visitors whenever I pleased (whether they asked to see my collection or not).

Then I graduated and attempted to settle in a new city, bouncing between apartments and moving five times in six months (finding affordable rent is hard!). Every time I moved, I had to tote my record player and vinyls across San Francisco. By my fifth move, I was over it and got rid of my record collection. I know admitting my willingness to abandon vinyl in an essay about the wonders of physical media is blasphemy, but so it goes. For the next decade, I embraced the convenience and cost-savings of Spotify. I didn't own my music, but I also didn't have to dedicate mental energy to storing and transporting my love of the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Years later, I regret this decision. Music was integral to my identity growing up; I spent countless hours on iTunes stressing over $0.99 song purchases and listening to 30-second music samples. Nowadays, I throw on Spotify's AI DJ, surrendering to the curation of a large language model—the single laziest way to discover new music (if at all). Recently, someone asked who my favorite band is, and it took me a minute to think about it (because I simply forgot). Is this a big deal? Cosmically, no. But for the 19-year-old version of myself who agonized over record purchases, this is high treason.

Much of the discussion surrounding music distribution treats physical vs. digital media as a zero-sum game, thus making it surprising that the two might complement one another. Why not Spotify AND vinyl? I understand this option is not particularly mind-blowing, but, personally, it really cooked my noodle. Streaming is the most efficient medium for music listening in terms of cost, accessibility, and storage, while vinyl offers an ability to express oneself in material form (and better sound quality, I guess). In embracing both formats, music fans decouple cultural self-expression from cultural consumption.

A few months ago, I walked into a record store and bought Bruce Springsteen's "Born to Run." I do not own a record player, so when I showed my wife this purchase, she inevitably asked why I did this. At the time, I didn't have a good answer to her question. This purchase was not premeditated—I just walked into the store, grabbed the record, and bought it (in the span of three minutes). For the next few days, I turned this question over in my mind, "why buy this album if I may never play it?"

In researching vinyl's resurgence, I've begun to better understand my own purchasing behavior. My dad grew up in the Philadelphia-New Jersey area of the United States in the 1970s, which means he had no choice but to be religiously devoted to Bruce Springsteen. When I came of age, Springsteen was one of the first cultural objects introduced to me. Throw in the fact that Bruce's music touches on the relationship between fathers and sons, and I, too, have no choice but to love this music.

Owning "Born to Run" is a reminder of my cultural origins—that this aspect of personality exists—and that through ownership, there is a material extension of this formative experience. Nobody can take "Born to Run" away from me, whether that be a Spotify price hike, internet outage, Crowdstrike outage, content licensing disagreement, or a well-written essay by John Philip Sousa.

"Canned music" isn't so pernicious when you can hold it in your hands.

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]