- Stat Significant

- Posts

- Unpacking the Rise of Fan Fiction: From 'Star Trek' to 'Twilight'—A Statistical Analysis

Unpacking the Rise of Fan Fiction: From 'Star Trek' to 'Twilight'—A Statistical Analysis

An exploration of modern fan fiction and the unique demography of its participants.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002). Credit: Warner Brothers.

Intro: Fan Fiction, From 19 BC Onwards

The story of fan fiction begins well before our modern age of superheroes, wizards, and intergalactic explorers. Before amateur reinterpretations of Twilight, Star Trek, and Iron Man, there was Virgil's Aeneid.

Published in 19 BC, Virgil's Aeneid is often cited (somewhat ironically) as one of the first known instances of "fan fiction," with Virgil reimaging events and themes from Homer's Illiad and Odyssey.

Since the Aeneid, countless adaptations have reconceptualized well-known characters and fictional worlds, including:

Numerous Shakespearean Works: Shakespeare frequently adapted existing stories, including "Romeo and Juliet" (based on "The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet") and "Othello" (inspired by an Italian tale called "The Moorish Captain").

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes: Following the success of Cervantes' Don Quixote, an anonymous author published an unauthorized sequel. Cervantes was so angry that he quickly responded with his own Don Quixote sequel, addressing and discrediting the unofficial continuation.

Jane Austen: Jane Austen fans, affectionately known as "Austenites," have a long tradition of reimagining her works, including sequels to her unfinished novel The Watsons and wildly imaginative adaptations like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

Today, fan fiction lives online and typically involves characters protected by copyright law.

Over the past two decades, fan fiction communities have grown exponentially as daily life has rapidly migrated online, and popular culture has coalesced around a handful of well-known media properties (Star Wars, Marvel, etc.). This distinctive corner of the internet allows fans to celebrate cultural artifacts and cultivate connection through a shared love of story.

So today, we'll explore the rise of modern fan fiction, examine the unique demography of its participants, and contemplate the value of this pastime in a world of Disney+ and endless Star Wars reboots.

The Rise of Fan Fiction

Contemporary fan fiction stems from the most enthralling of origins—copyright law(!!!).

Codified in the early 20th century, modern copyright laws granted private companies ownership of popular characters and stories, prompting fans to expand upon these myths through non-commercial channels.

If you wrote about Cinderella in the early 1800s, there were no repercussions—your works could be adapted into stage plays and distributed worldwide. Today, your Cinderella adaptation would entangle you in a complex and costly legal battle with Disney (unless this work was published on fanfiction.net). As a result, contemporary fan fiction is rigorously defined as a non-commercial work based on characters, settings, or worlds from existing copyrighted media—with an overwhelming emphasis on "non-commercial."

The blueprint for 21st-century fan fiction can be traced back to Star Trek's cult-like following in the late 1960s. This period saw the rise of Trekkie fanzines, with publications like "Spockanalia" publishing some of the earliest examples of modern fan fiction. Fanzines would serve as the focal point of fan culture until the mid-1990s when they were swiftly overtaken by the emergence of online forums.

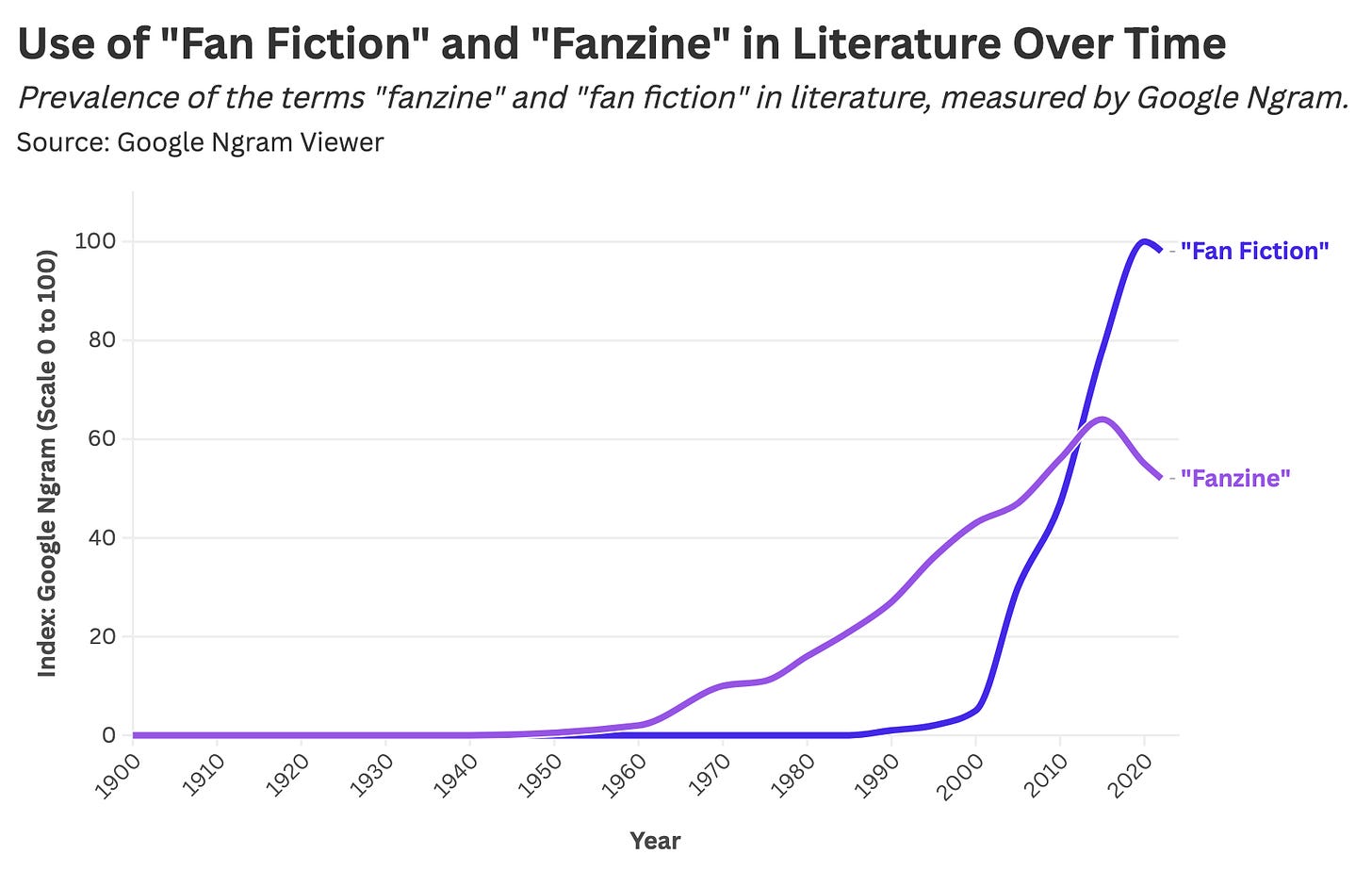

Using Google Ngram Viewer, we can track historical mentions of the terms "fanzine" and "fan fiction" to chart the rise and fall of these formats over time. According to Google data, the term "fanzine" rose to prominence in the early 1960s, steadily growing in popularity until the mid-1990s, when fan culture migrated online and blogging platforms sparked an explosion of "fan fiction."

Writers have been reimagining popular myths for centuries, yet our contemporary understanding of "fan fiction" is deeply intertwined with digital culture.

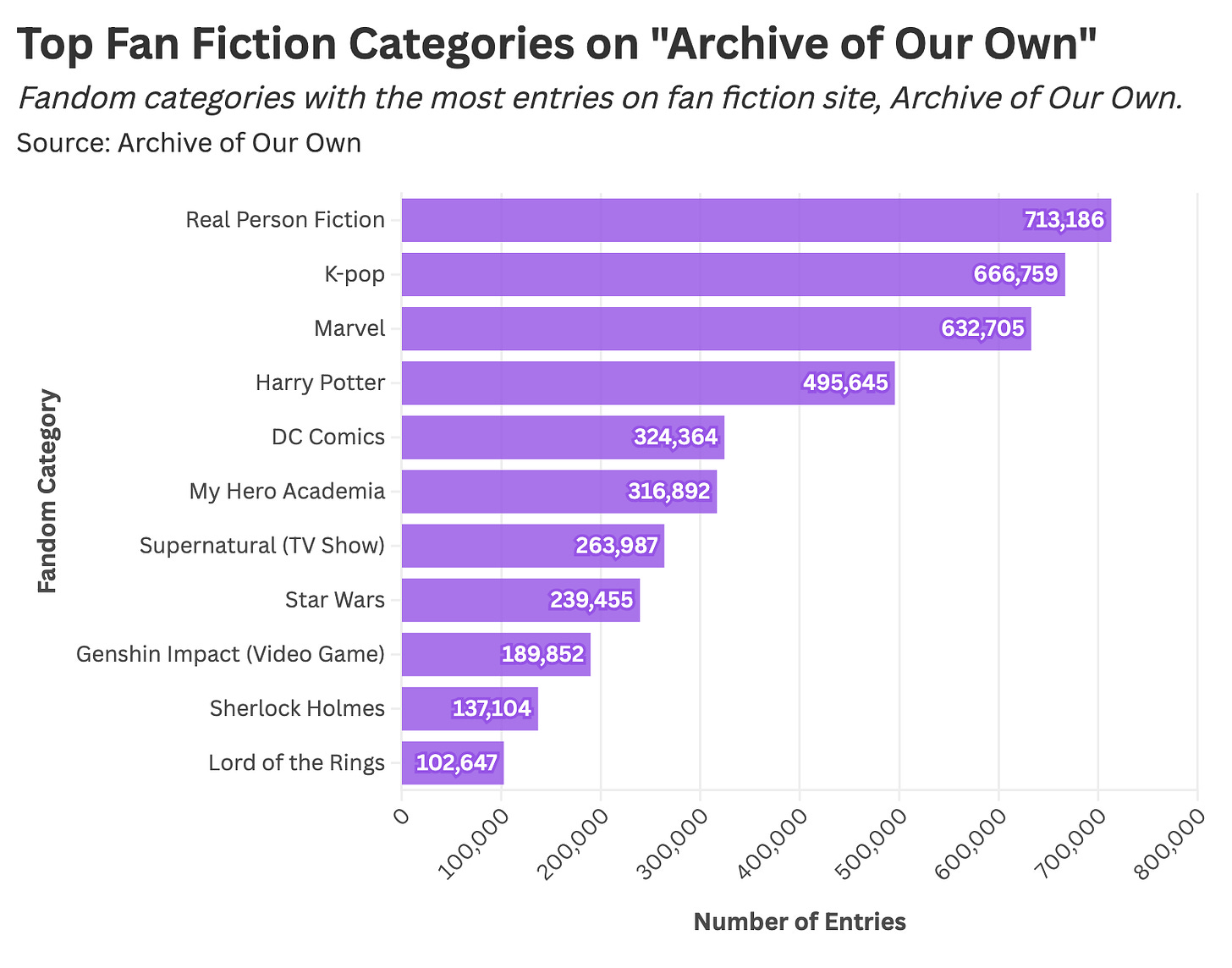

So, which imagined worlds dominate 21st-century fan fiction? When we analyze the most popular categories on Archive of Our Own (the largest online repository of fan fiction), the site's most prolific topics concern celebrities and well-known fictional universes.

"Real Person Fiction," Archive of Our Own's most popular subject, encompasses stories about pop celebrities, historical figures, and ordinary individuals. Said differently, "fandom" can go beyond fiction worlds.

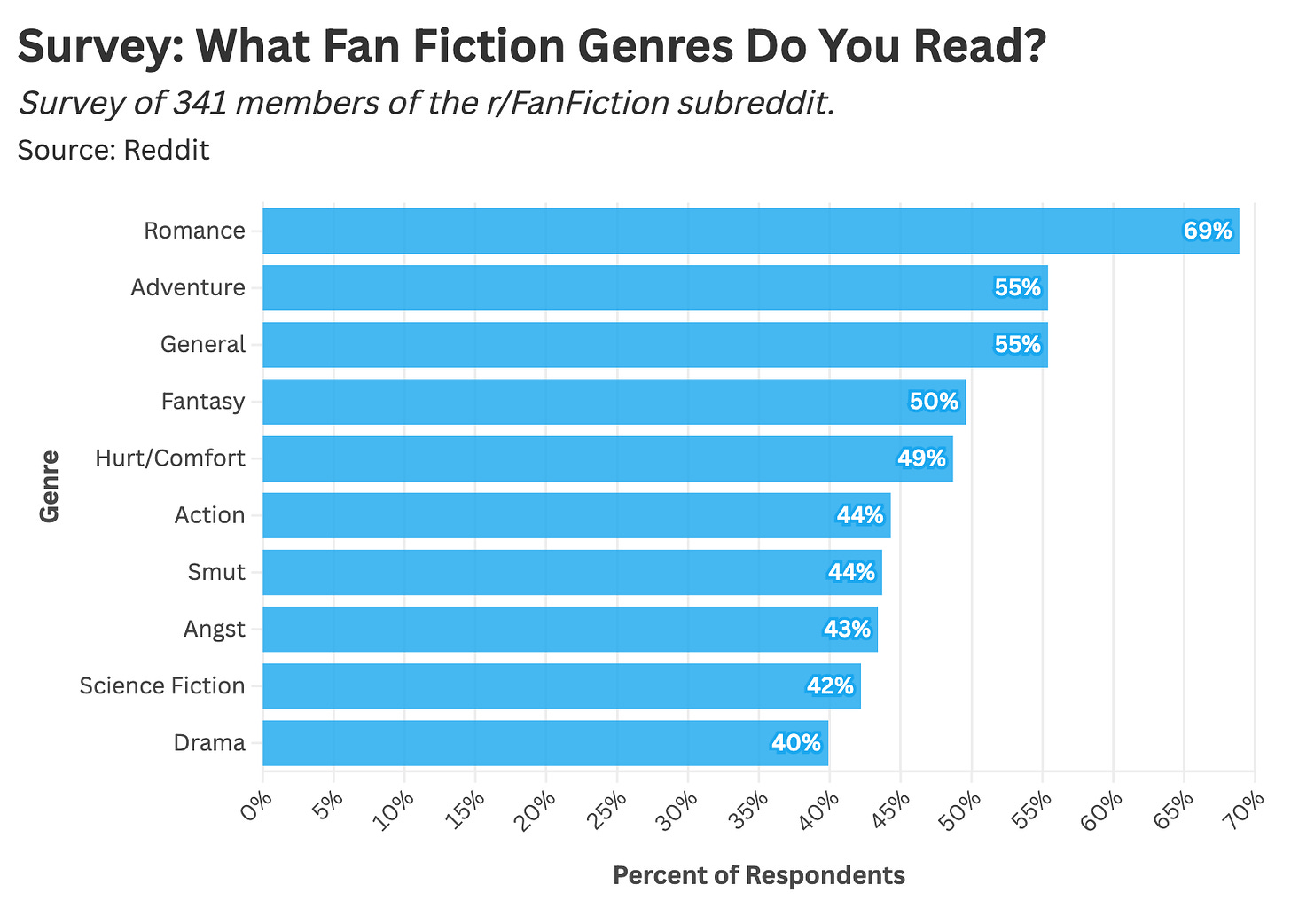

And what type of stories spring from the minds of fan fiction writers? According to a Reddit poll of r/FanFiction members, preferred fan fic subgenres include "romance" and "adventure."

So far, our fan fiction research aligns with prior expectations—at least my own—depicting a digital-native community celebrating pop stars, Spider-Man, and wizards (often involving romance, but not necessarily). I was about to move on from this analysis—deeming it unworthy of a full-fledged post—until I started digging into the demographics of fan fiction communities.

If you're even the least bit cynical about Marvel, Disney+, or the endless slog of Harry Potter prequels then you may want to stay tuned for part two—proof that fandom isn't all that bad.

The Demographics of Fan Fiction Communities

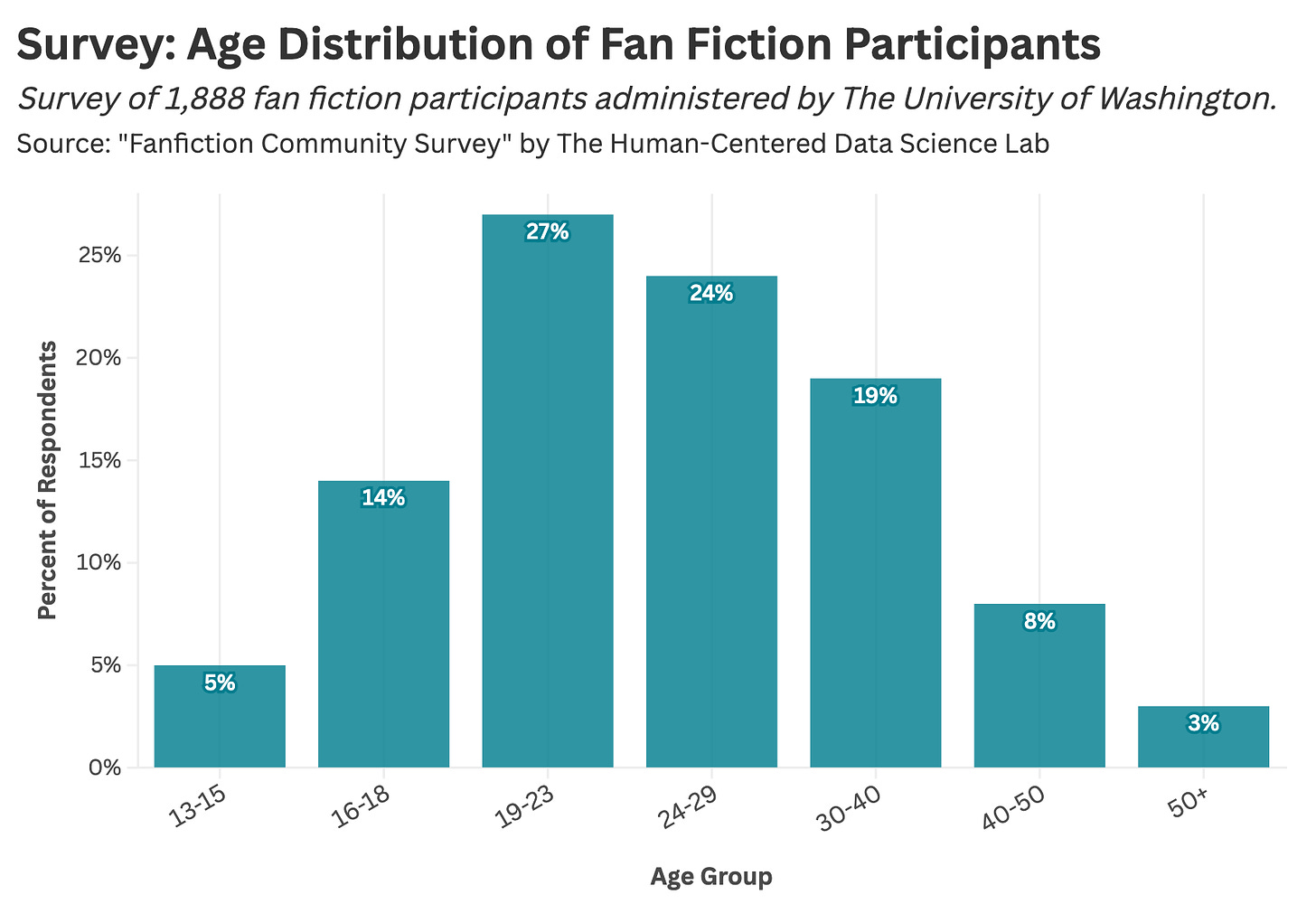

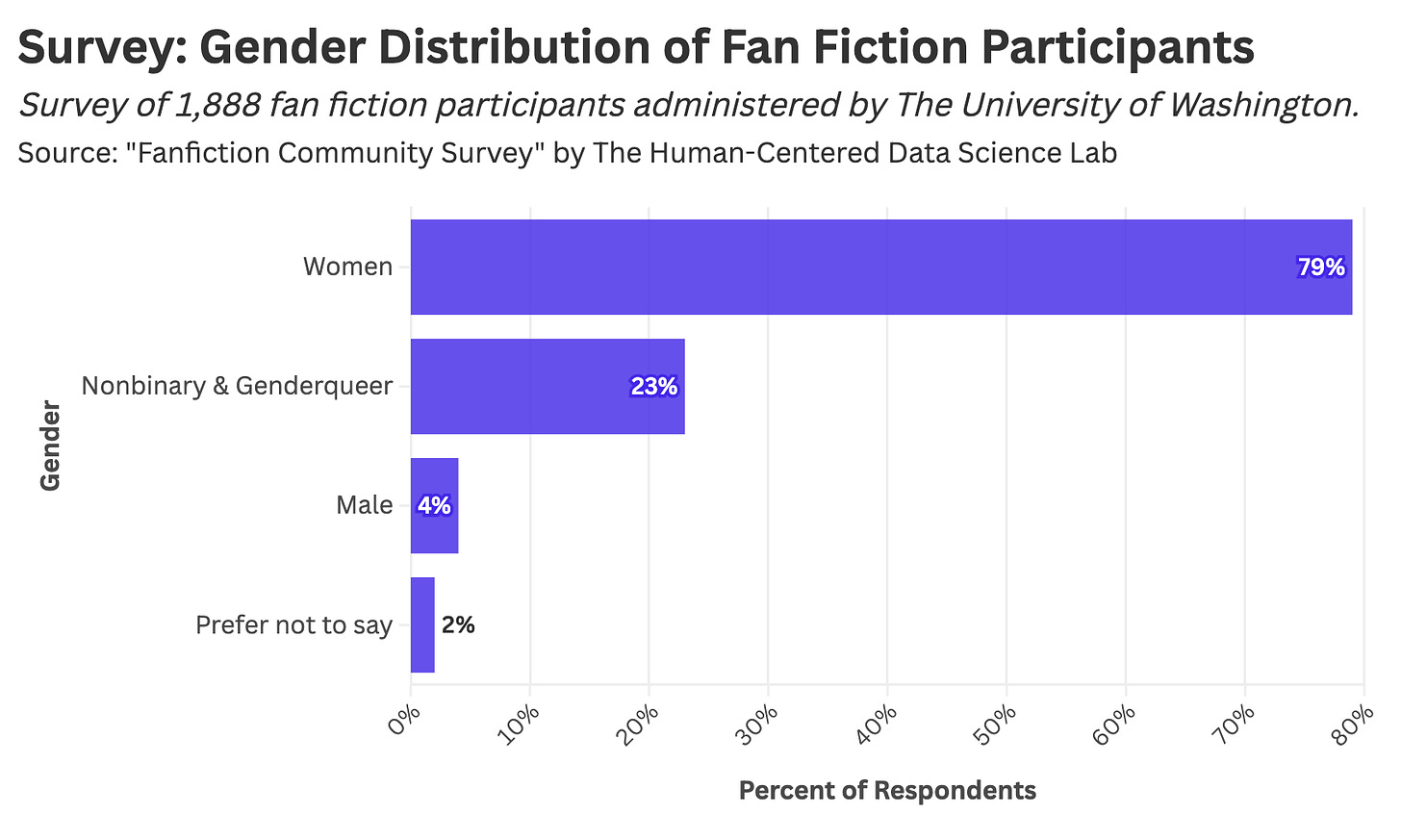

In 2018, the University of Washington's Human-Centered Data Lab surveyed over 1,800 fan fiction writers and readers, collecting information on their backgrounds and relationship with the storytelling format.

Most fan fiction participants in the Washington survey fell between their mid-teens and late twenties.

This age range aligns with other studies, suggesting that individuals often "age in" and "age out" of fan fiction, with the medium offering considerable benefit to those navigating early adulthood.

Once more, the University of Washington survey found fan fiction to be most popular among those identifying as women, nonbinary, and genderqueer, with only four percent of respondents selecting "male" for their gender.

The Human-Centered Data Lab's findings are similar to those of other demographic analyses, with subjects typically skewing female and nonbinary (though this particular survey has the lowest proportion of male-identifying respondents).

Furthermore, a 2018 r/FanFiction Reddit survey regarding sexual orientation saw over 49% of subjects identifying as LGBTQ+:

Heterosexual: 50.4%

Bisexual: 17.6%

Asexual: 10%

Homosexual: 5.6%

Other (Pansexual, Queer, etc.): 16.4%

Even if this survey is not fully representative of the prototypical fan fiction participant, it highlights the significant value these forums offer to queer communities.

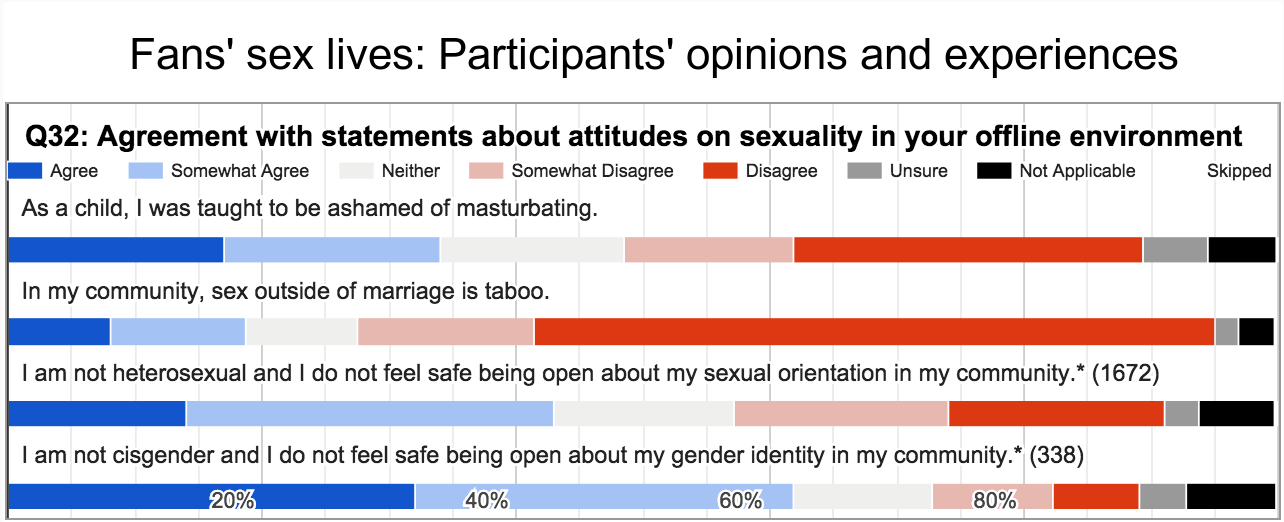

In 2016, The Three-Patch Podcast, a show dedicated to exploring fandom culture and social issues, polled 2,200 fan fiction readers regarding their "attitudes on sexuality in their offline environment." Many survey respondents reported concern expressing aspects of identity in their community.

Source: The Three Patch Podcast.

I'm always wary of overgeneralizing from a constellation of data points, given there are myriad reasons why someone might be drawn to fan fiction. Still, there is likely a meaningful population of fan fiction participants who frequent these forums because they offer a space to explore diverse identities in an anonymous and supportive environment. Furthermore, this medium can serve as a crucial outlet for people in their teens and twenties, providing a community for creativity and self-expression during their formative years.

While these insights are not universal, they underscore fan fiction's significance as a haven for young people and marginalized communities.

Final Thoughts: A Lifelong Commitment to Jar Jar Binks

Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999). Source: 20th Century Studios.

The past five years have seen Hollywood churn out some eminently terrible franchise garbage: Madame Web, Morbius, Fast X, Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire, The Flash, and all the Jurassic Park legi-sequels. As such, it's easy to grow cynical over the meaning of Harry Potter and Captain America in a world where each story is ostensibly crafted to spark anticipation for the next story (and the story after that, and so on). Have these characters become little more than totems of corporate strategy, allowing Disney to siphon every last dollar from a captive fanbase (until the next reboot)? And as a fan, what are you signing up for when you develop a fascination with Harry Potter or Han Solo?

My dad first showed me Star Wars when I was five years old. I saw A New Hope on the big screen and thought it was the coolest thing I had ever seen—meaning I would be a Star Wars fan for the rest of my life. That said, I was five years old and didn't realize my affinity for this cinematic universe entailed future commitments to The Phantom Menace, The Force Awakens, Hayden Christianson, numerous lightsaber purchases, a passing interest in the actions of Disney CEO Bob Iger, The Last Jedi, Disney+, or Jar Jar Binks. I just thought I was watching a movie with my dad. It's with this in mind that I've come to view fandom (as controlled by a company like Disney or Netflix) as everything wrong with modern entertainment.

In buying and owning these characters, Disney secures lifelong patronage. Something as simple as a parent sharing Iron Man with their child is inextricably linked to Disney's growth strategy (I often envision some corporate marketer delivering a soulless presentation on Disney's customer life cycle that emphasizes the acquisition of lifelong fandom in early adolescence 🤮). Needless to say, I'm extremely disillusioned with fan culture—with the exception of fan fiction(!!!).

Before starting my analysis, I knew two things about fan fiction:

That 50 Shades of Grey began as Twilight fan fiction (true story).

That fan fiction often concerns sexual situations between two well-known characters.

After compiling my research, I feel pretty stupid for reducing this community to pithy stereotypes. Better yet, fan fiction allows devotees to celebrate Luke Skywalker or The Avengers without Disney making money.

A beloved character or myth belonging to a corporation is a relatively new concept (in the course of human history). Thankfully—mercifully—there is a delineation between commercial and non-commercial works. A character like Chewbacca or Hagrid can belong to anyone—they can help you find community and explore different facets of identity—as long as no one plans to make money off them (because that's where Disney draws the line).

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Looking to produce data-centric editorial content? Email [email protected]