- Stat Significant

- Posts

- The Rise and (Overstated) Fall of Radio. A Statistical Analysis

The Rise and (Overstated) Fall of Radio. A Statistical Analysis

Examining radio's rapid adoption and surprising cultural endurance.

Frasier (1993). Credit: NBC.

Intro: First, There Was Radio

Long before CNN, Fox News, Tumblr, Bluesky, and Substack Notes, there was radio. Introduced in the early 1920s—coincidentally at the dawn of a global economic depression—radio revolutionized the public's relationship with news and music.

Consider Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Fireside Chats," a series of radio addresses delivered between 1933 and 1944. Roosevelt's broadcasts, which allowed the president to communicate directly with the American people (absent a news organization), garnered an enormous audience. His December 9th, 1941 address (two days after Pearl Harbor) attracted an estimated 62.1 million listeners, roughly 46% of all Americans.

Roosevelt's fireside chats spawned unprecedented public engagement, with White House mail increasing from 5,000 to 50,000 letters a week immediately following his first address.

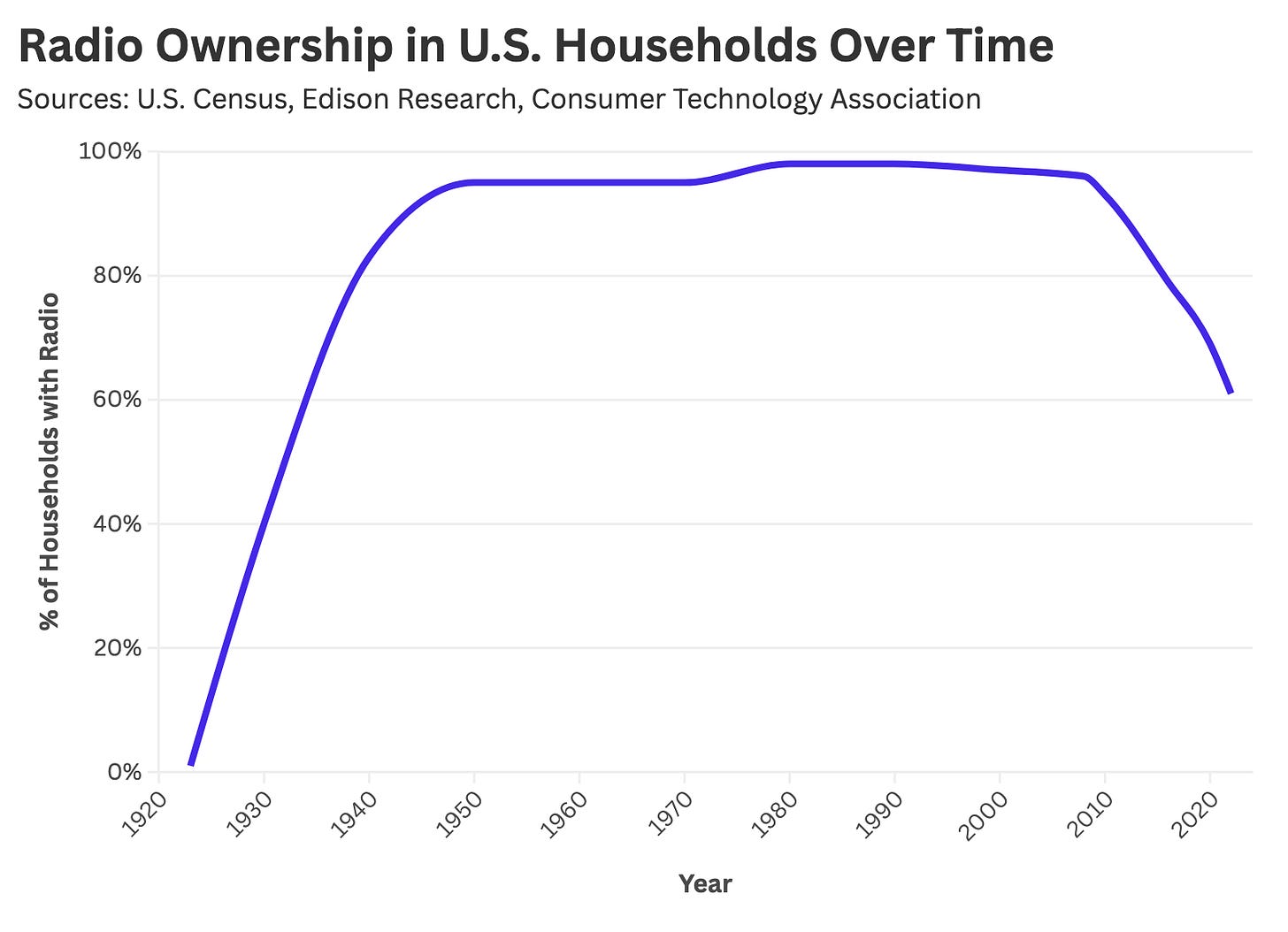

By the end of the 20th century, 98% of households owned a radio. Unsurprisingly, this figure has rapidly changed over the past two decades, as radio programs now compete with Spotify, The Joe Rogan Experience, Wirecutter toaster recommendations, 'Hawk Tuah' content, people tweeting about Bluesky as if this one will be different, and every other passing thought documented by humankind.

So today, we'll explore radio's rise and (overstated) fall, examining the technology's immediate adoption, ever-proliferating competition, and enduring appeal.

The Rise and (Moderate) Fall of Radio

Radio technology was initially developed for military application in the early 20th century, with the U.S. Navy pioneering wireless communication for maritime operations. The first consumer radio was introduced in 1920, coinciding with the establishment of commercial radio stations like KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and WWJ in Detroit, Michigan.

In 1923, household radio adoption was estimated at 1%; by 1937, this figure had reached an astounding 75%. Ownership would eventually peak at 98% and remain at this level for over six decades.

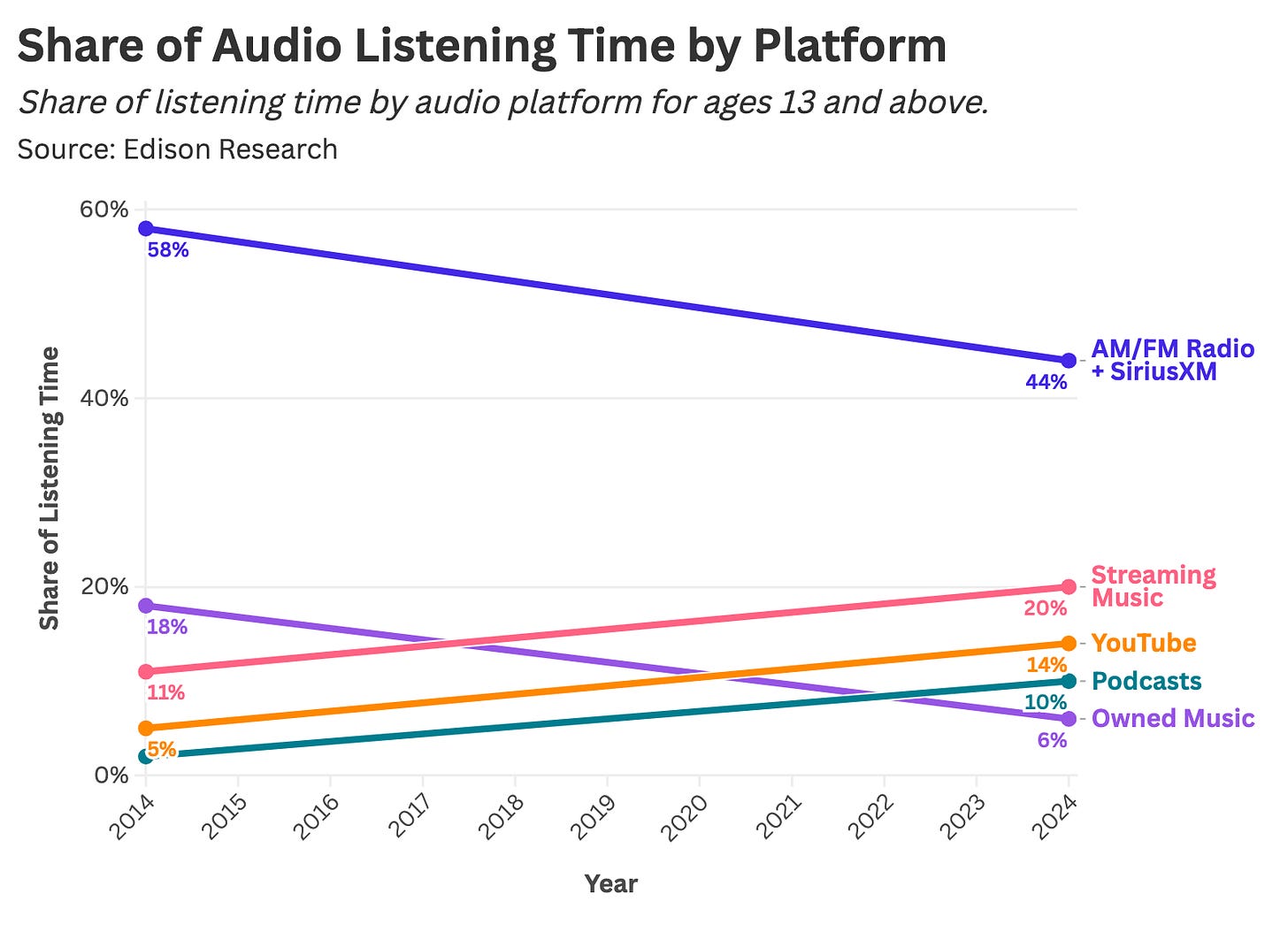

However, the past twenty years have seen the introduction of numerous digital audio platforms like iTunes, Spotify, and YouTube that challenged the ubiquity of AM/FM radio. When we compare 2014 and 2024 data from Edison's "Share of Ear" study, we find a meaningful decline in AM/FM and Sirius radio listenership in tandem with rising streaming, podcast, and YouTube usage.

This decline is significant but not as gargantuan as one might anticipate. Many consumer technologies that defined late 20th-century life—such as VCRs, DVDs, TiVo, and CDs—are now commercially extinct. Can radio withstand competition from digital media, or is its path to obsolescence simply more gradual? I suspect the latter, though the exact timeline is anyone's guess.

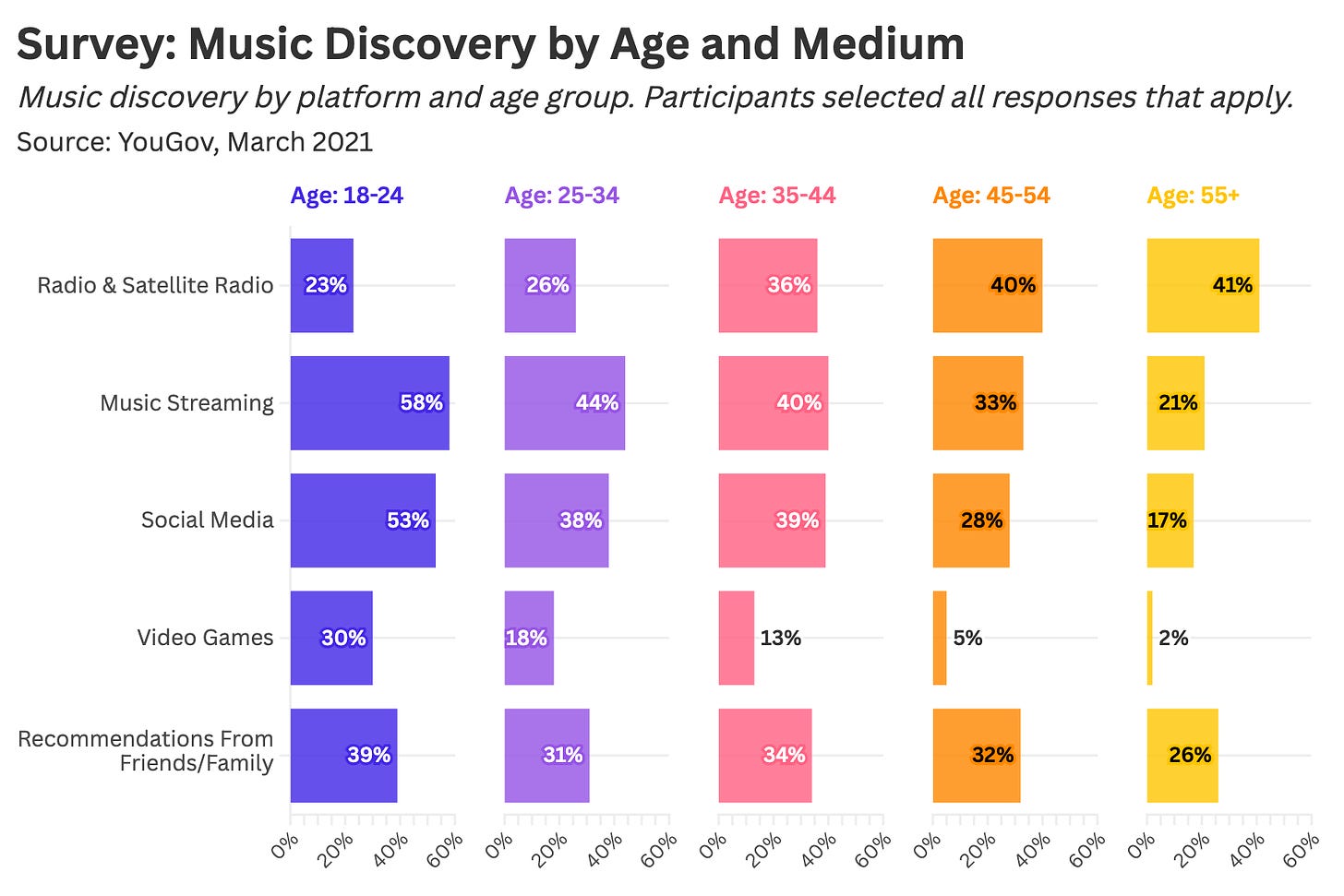

Consider a recent YouGov survey regarding music discovery vis-a-vis consumer age. Social media and streaming have become the go-to platforms for music discovery among younger listeners, while radio sees dwindling use with each passing generation.

Radio is no longer the most entertaining modality for news and music consumption—at least for younger generations—but the medium is far from dead. So, who (or what) is keeping radio alive, and what do holdouts find so endearing about this hundred-year-old technology?

The Enduring Appeal of Radio

With each passing decade, the lifespan of widely adopted media formats grows shorter and shorter. If you want proof of this phenomenon, look no further than the home video market.

In the beginning, there was Betamax, then VHS and Laserdisc, followed by DVDs, Blu-ray, and 4k UHD, which were, then, subsequently subsumed by streaming, YouTube, and TikTok. In hindsight, there is an inevitability to each format's extinction, but that's not how these products were advertised at the time.

Each medium, be it VHS or CD, presents itself as "the end of history" for consumers—that innovation ends with this technology—only to have those same marketers sell you an upgrade a few years later. The only certainty is that you'll soon give your time and money to some new-fangled entertainment app or service that has yet to be invented.

Anyway, back to radio: this inescapable and expensive history of media obsolescence makes radio's endurance all the more surprising. How is this medium still dominating "share of ear"?

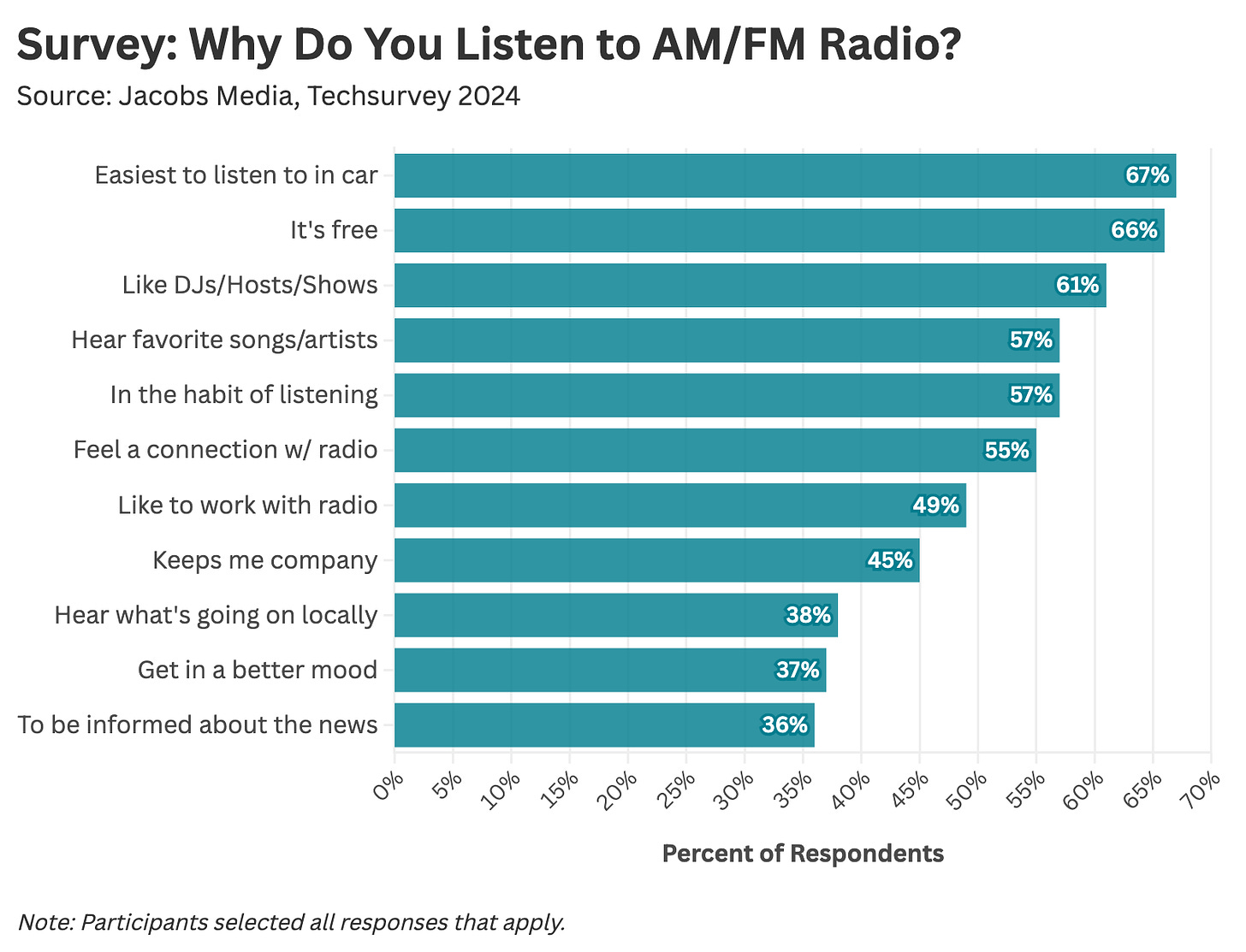

Thankfully, friend of the newsletter Jacobs Media conducts a yearly poll on the state of AM/FM radio, gathering insights on listener preferences and usage patterns. When asked "why [they] listen to AM/FM radio," respondents cited convenience while driving, cost, and a connection with local radio personalities.

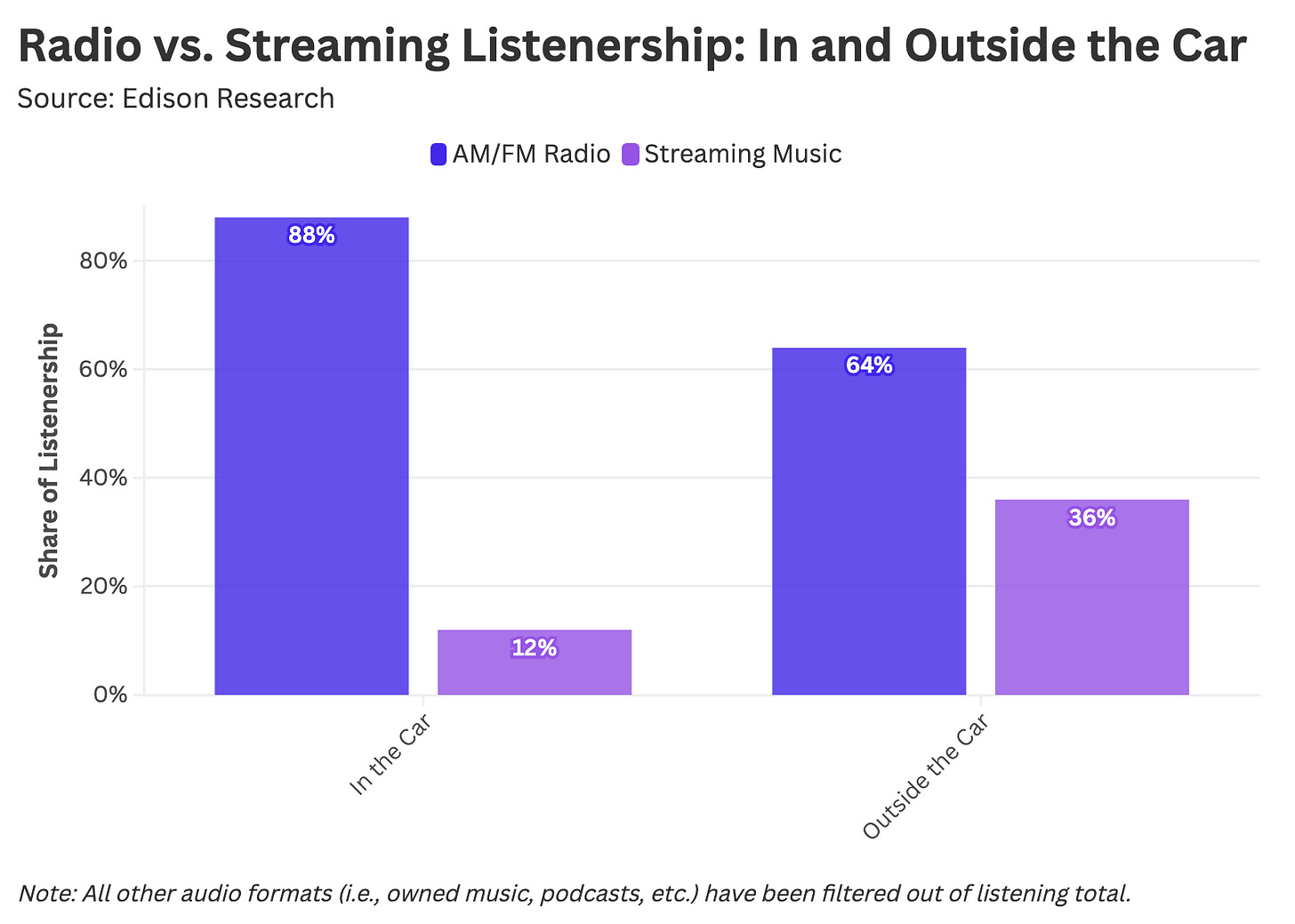

Radio's near-universal presence in automotive dashboards remains one of the medium's key competitive advantages. In fact, Edison Research has found significant disparities in radio usage (versus streaming) when comparing behavior in and outside of a car.

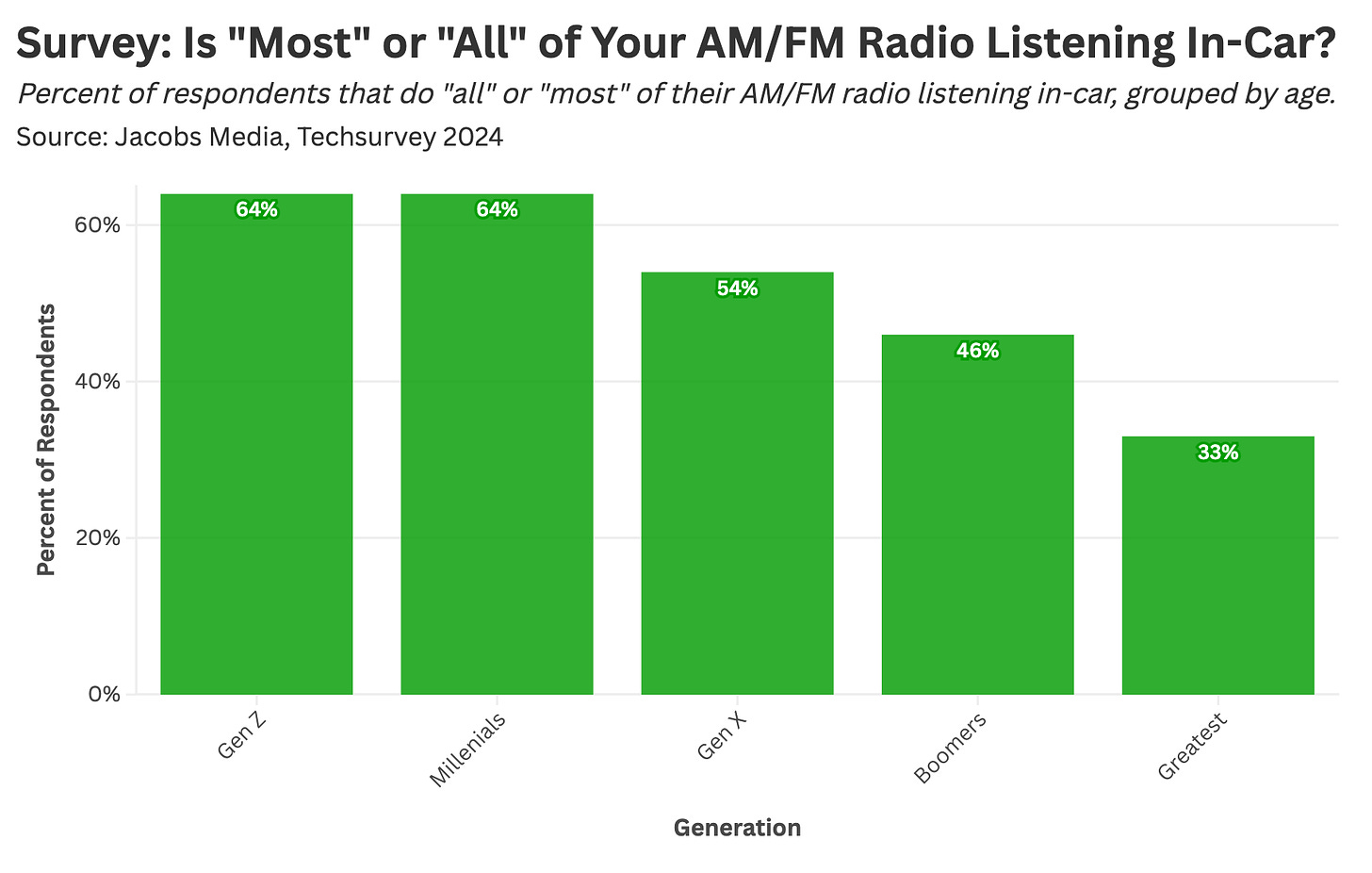

According to research from Jacobs Media, younger listeners primarily consume radio while driving, a stark departure from older generations.

As a younger millennial, this squares with my personal experience, as I drive infrequently and only listen to the radio while in Ubers. I know this pithy remark will frustrate readers above a certain age, but rest assured, one day I'll be on the receiving end of such a sentiment. Two decades from now, someone from Gen Alpha will tell me they use Snapchat or Instagram ironically and it will shatter my sense of self—but today is not that day!

So far, our research suggests that radio's relevance is heavily tied to its convenience and accessibility in cars. While this is undeniably true, it only captures part of the medium's appeal.

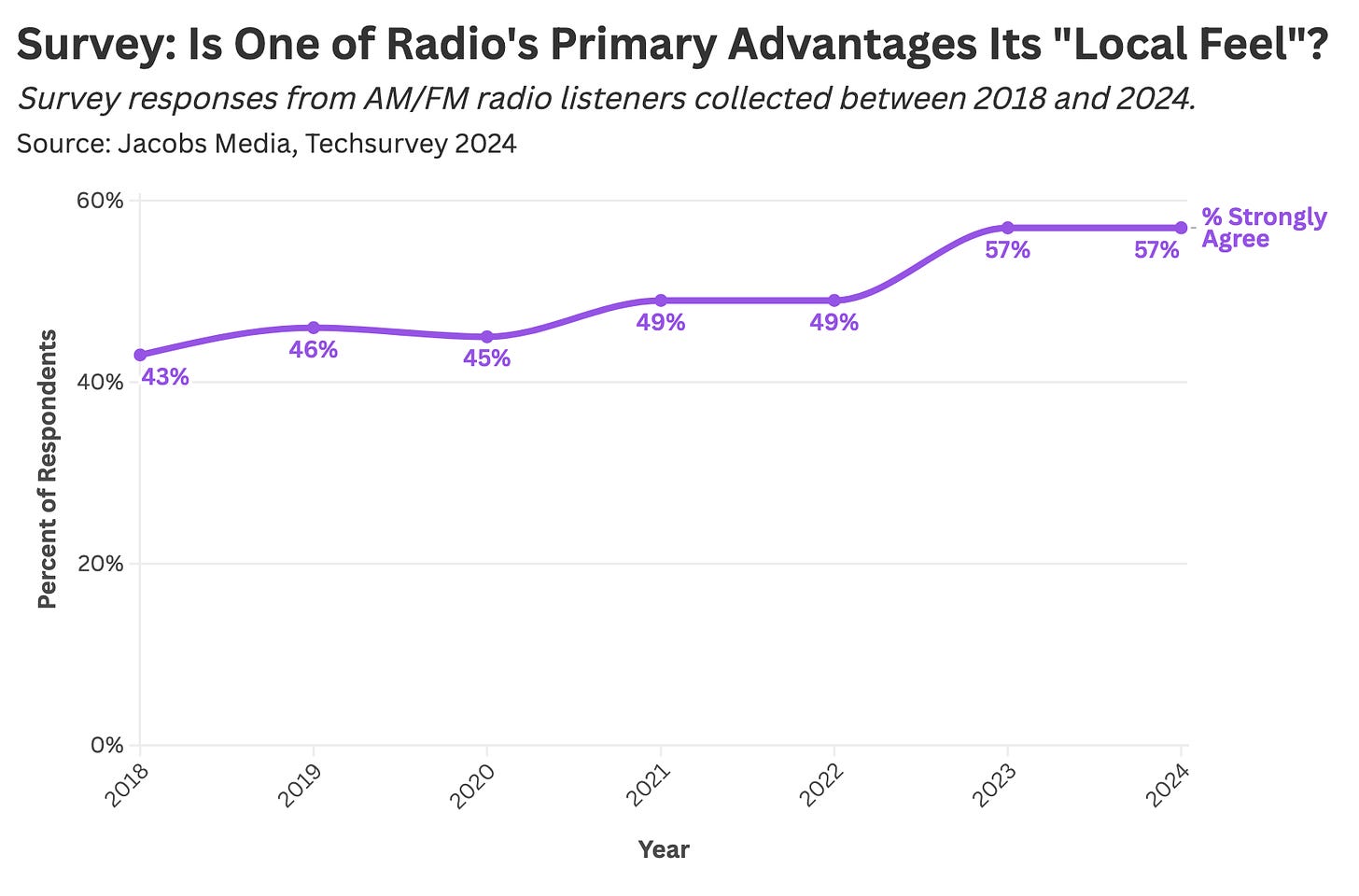

Increasingly, listeners highlight "local feel" as one of radio's primary advantages.

Radio offers local news, daily weather reports, media personalities who live in the same city as you, traffic reports, and weekly digests regarding regional entertainment. In fact, given radio's enduring reach, this format stands as the last (somewhat thriving) bastion of local media.

Linear TV is in a state of rapid decline, rendering local broadcast journalism obsolete. Print news is virtually dead; outlets who've effectively transitioned online increasingly gear coverage toward national and global events. I'm often surprised when I see a New York Times article about the New York metropolitan area, as I've come to associate the "New York" part of their name with a provincial mindset rather than an actual city.

On the other hand, radio has remained relevant through its connection to place—in both form and function. You can leave your house, get in your car, turn on your favorite AM/FM radio station, learn about local news and gatherings from someone in your city, and it's all free. A disc jockey can even inform you of a regional traffic jam you're currently sitting in—which is hyperlocal coverage at its best.

Final Thoughts: Trading Serendipidity for Specificity

Good Morning, Vietnam (1987). Credit: Buena Vista Pictures Distribution.

I recently had a dentist appointment that (inexplicably) lasted two hours. For two long hours, various dental professionals poked and prodded my teeth, with the office radio serving as my only distraction. When I asked my dentist about his choice of audio, he casually remarked, "We like to groove here," which was a pretty cool thing to say.

My two-hour reintroduction to radio was a rollercoaster of highs and lows:

The Highs: I've increasingly struggled to find new music over the last few years—a well-worn sociological phenomenon afflicting those exiting their twenties (and beyond). As such, I've mostly given up on active music discovery, settling for Spotify's AI D.J., who feeds me a never-ending buffet of songs I enjoyed during my teenage years. And yet, while getting my teeth unpleasantly blasted by some sort of cleaning apparatus, I discovered two songs I really enjoyed—in the span of ten minutes! "Perhaps this is what our culture has been missing!" I thought to myself. Passive content consumption (by way of radio) allows for moments of serendipity—the ability to discover media outside a self-imposed echo chamber. Why isn't everybody listening to AM/FM radio?!?

The Lows: Immediately following my newfound commitment to radio, I was subjected to an inane conversation about "Glicked"—a clumsy attempt to manufacture another "Barbenheimer" by pairing Gladiator II and Wicked. The hosts droned on endlessly, filling the airwaves with words that amounted to nothing. If I were listening to a podcast, I simply would have turned the program off. Perhaps this is the trade-off many are unwilling to make—people will readily sacrifice discovery and "local feel" for total control of their media diet.

As a kid, I regularly tuned into my local radio station's "Top 25" music countdown. Most weeks, I was unlikely to discover something I enjoyed, but occasionally, I'd stumble upon a new song or artist that made all the hassle worthwhile. Post-iTunes and -Spotify, I no longer have this sort of patience.

Perhaps competition amongst Spotify, AM/FM radio, YouTube, and The Joe Rogan Experience is not a zero-sum death match for "share of ear." Maybe these platforms serve different use cases, rendering radio eternally relevant for those in cars who want to expand their cultural horizons and know a bit more about their community. Perhaps if everyone was forced to endure two hours of radio at the dentist's office, we'd never stop discovering new music, and we'd feel a deeper connection to the world around us.