- Stat Significant

- Posts

- The Rise and Fall of the Hollywood Movie Soundtrack: A Statistical Analysis

The Rise and Fall of the Hollywood Movie Soundtrack: A Statistical Analysis

How blockbuster movie soundtracks took over Hollywood—and then disappeared.

Grease (1978). Credit: Paramount Pictures.

Intro: The Cash-Grab Pop Ballad

In 1996, film composer James Horner was putting the finishing touches on a new score when he ran into one final problem: deciding what music to play over the closing credits.

In the mid-1990s, studio films often ended with commercially oriented songs designed for radio play—such as “Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” or “Gangsta’s Paradise.” In this case, the movie’s director was adamant about avoiding a cash-grab pop ballad.

Horner was convinced that the movie’s instrumental theme would pair well with lyrics and moved forward without the director’s blessing. He recruited a well-known Canadian vocalist and recorded a demo in secret. A few weeks later, he unveiled the song, and the rest is history: James Cameron agreed to put “My Heart Will Go On” in Titanic. The track spent two weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100, and the film’s soundtrack sold more than 30 million copies.

Céline Dion’s “My Heart Will Go On” is the apotheosis of the movie-track megahit: one of the defining songs of the 1990s, buoyed by its association with the biggest movie ever made.

I recently stumbled across this anecdote and was struck by its quaintness: the pipeline between Hollywood and the music industry was so well-oiled that a covertly recorded song became a cultural sensation. Which made me wonder: what does that pipeline look like today? Does the film industry still produce hit songs?

So today, we’ll examine Hollywood’s ability to mint chart-topping tracks, how modern films deploy recorded music, and the economic incentives that shape the music-to-movie pipeline.

Learn More, Faster with Shortform’s Book Summaries

If your days are short and your reading list is long, check out Shortform.

Shortform creates concise, high-quality guides to the best non-fiction books. Think book summaries, but done well: Shortform breaks down key concepts, with additional analysis and exercises to help the insights stick.

From self-help to statistics — Shortform makes the world’s best ideas easier to access. Unlock thousands of titles for less than the price of one book.

The Rise and Fall of Movie Soundtracks

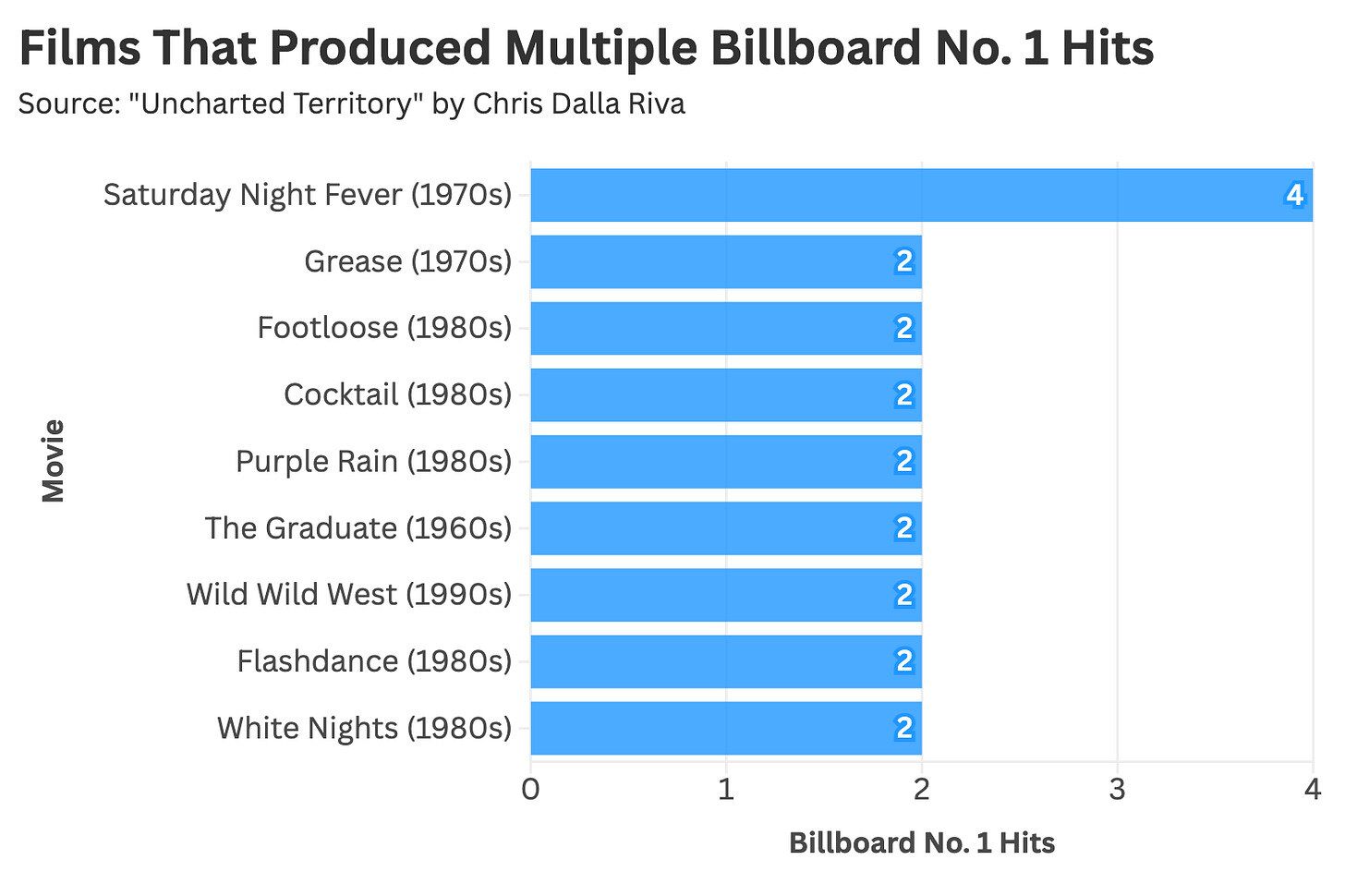

When it comes to movie soundtracks, there is before Saturday Night Fever and after. The 1977 disco-centric character study featured an original slate of Bee Gees songs, selling more than 40 million albums and spawning four chart-topping hits—a degree of cultural dominance that will likely never be replicated.

Author’s note: I watched Saturday Night Fever recently, expecting a glossy, feel-good musical full of stylish dance numbers. Wow, was I wrong. So very wrong! Apart from the Bee Gees soundtrack, this movie is a decidedly feel-bad portrait of down-on-their-luck twentysomethings whose only refuge is disco. Great music; surprisingly gritty movie.

Grease followed a year later, sending two songs to No. 1 and selling 35 million albums, and thus the era of big-budget soundtracks was born.

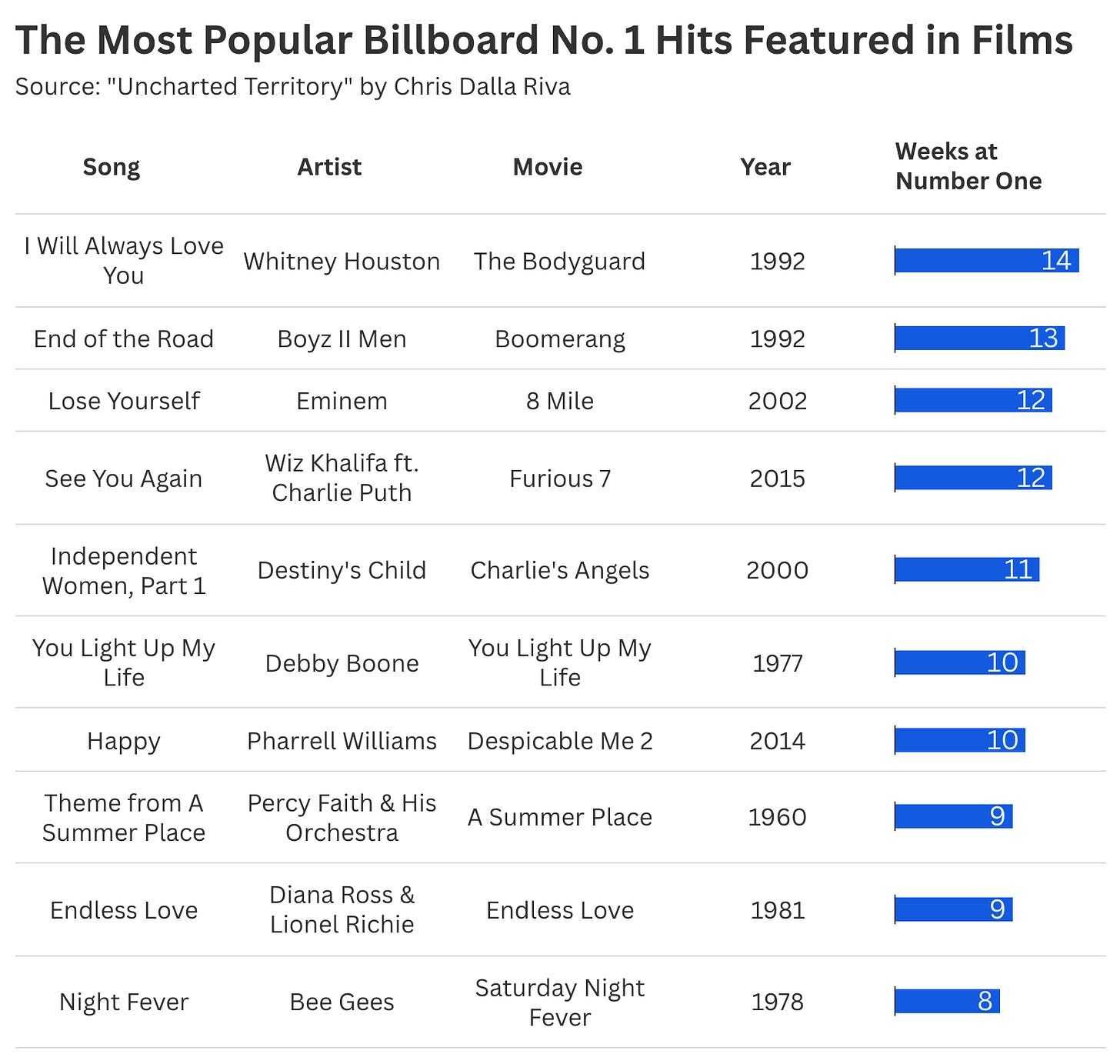

Since Billboard introduced the Hot 100, there have been 105 instances of chart-topping songs tied to contemporary films. While researching this essay, I was struck by how many pop staples were clumsily shoehorned into Hollywood projects.

For example, Boyz II Men’s “End of the Road” is from a totally-real movie called Boomerang, but the song plays during the closing credits and has no bearing on the film’s narrative. In many cases, a track’s cultural afterlife dwarfs the movie itself, like the song “Teenage Dirtbag,” which comes from a movie called Loser that allegedly exists.

Regardless of circumstance, some of the most popular tracks of the last century were popularized through Hollywood movie magic (or lazily during the end credits).

Following the twin successes of Grease and Saturday Night Fever, studios were eager to capitalize on this best-selling-soundtrack-via-blockbuster formula—and for two decades, they were extremely successful. The 1980s and 1990s delivered a steady run of best-selling movie albums, including Footloose, Dirty Dancing, Titanic, Top Gun, and Flashdance, among others.

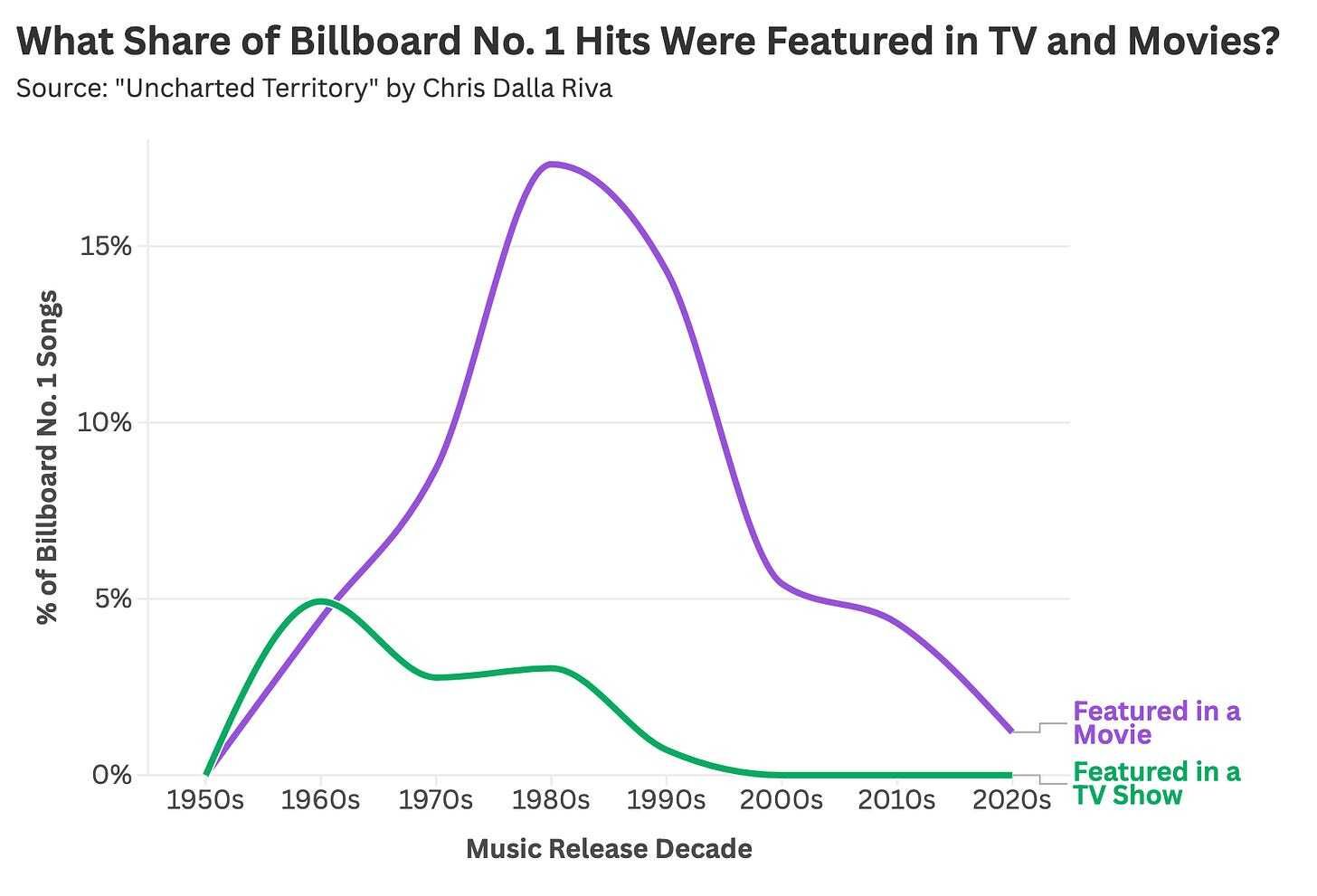

At the peak of the movie soundtrack craze, nearly 20 percent of chart-topping songs were tied to a film release. By contrast, television has rarely functioned as a hit-making machine for pop music (especially when you omit The Monkees).

The rise of the chart-topping soundtrack was more than a case of corporate mimicry. These songs thrived on MTV, which transformed film clips into ready-made music videos. Meanwhile, an increasingly consolidated entertainment industry meant that film studios and record labels often lived under the same corporate umbrella, creating undeniable corporate synergy (hooray for corporate synergy!). It was a good time to be a faceless conglomerate. So what changed?

The movie soundtrack’s decline tracks closely with the album’s commercial collapse. The 2000s brought Napster—and later iTunes—moving listeners from full records to individual tracks. With this shift, the economic incentives that once sustained blockbuster soundtracks largely disappeared.

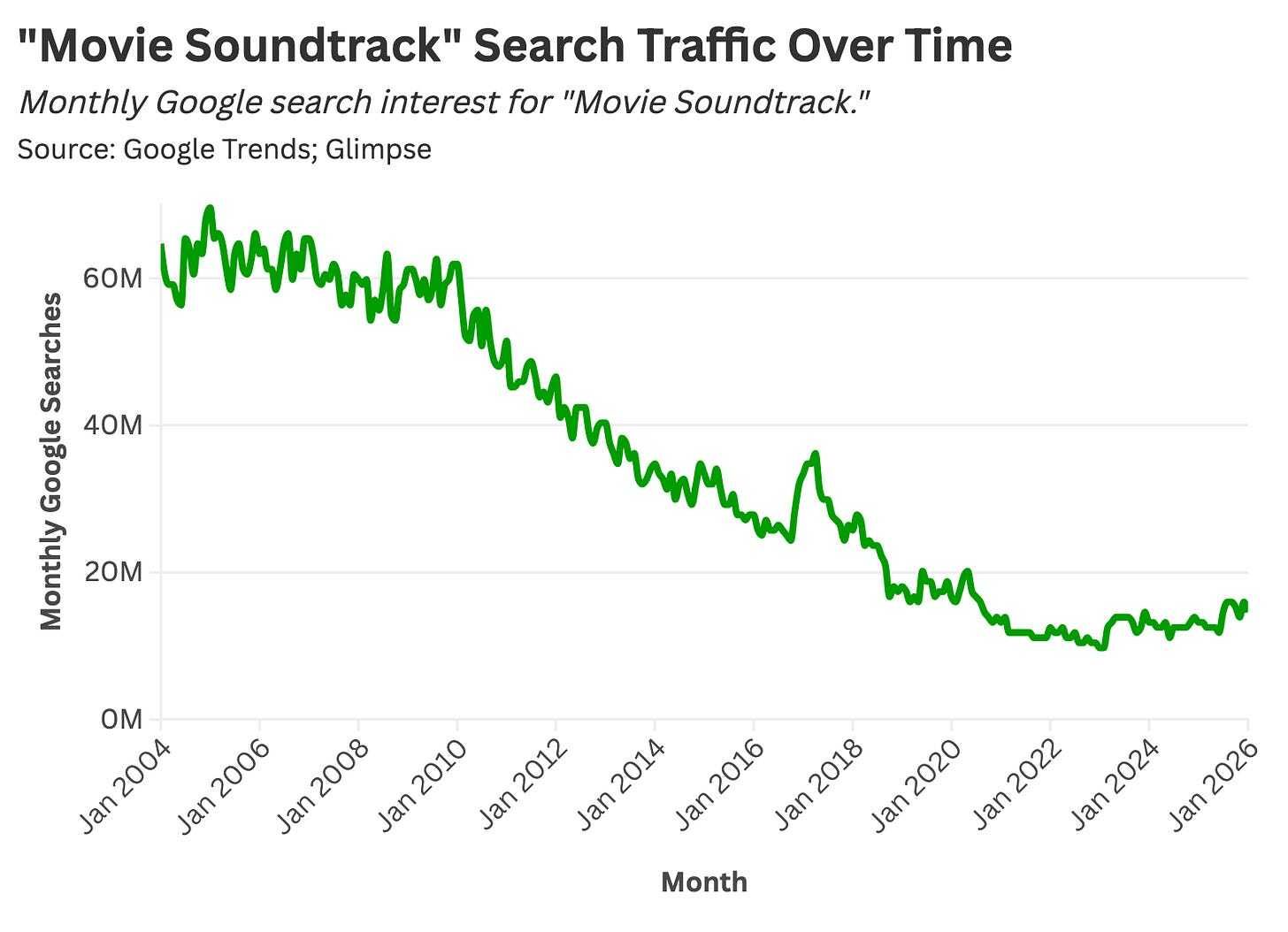

When we look at Google search volume for “movie soundtrack,” we see monthly queries begin to tank around 2008, when Steve Jobs’ iTunes ecosystem reached full maturity.

Prior to iTunes, someone would have to buy The Bodyguard soundtrack for $15 to hear Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.” Post-iTunes, you could buy that same track for $0.99 or stream it on Spotify, which minimally compensates the artist, record label, and movie studio.

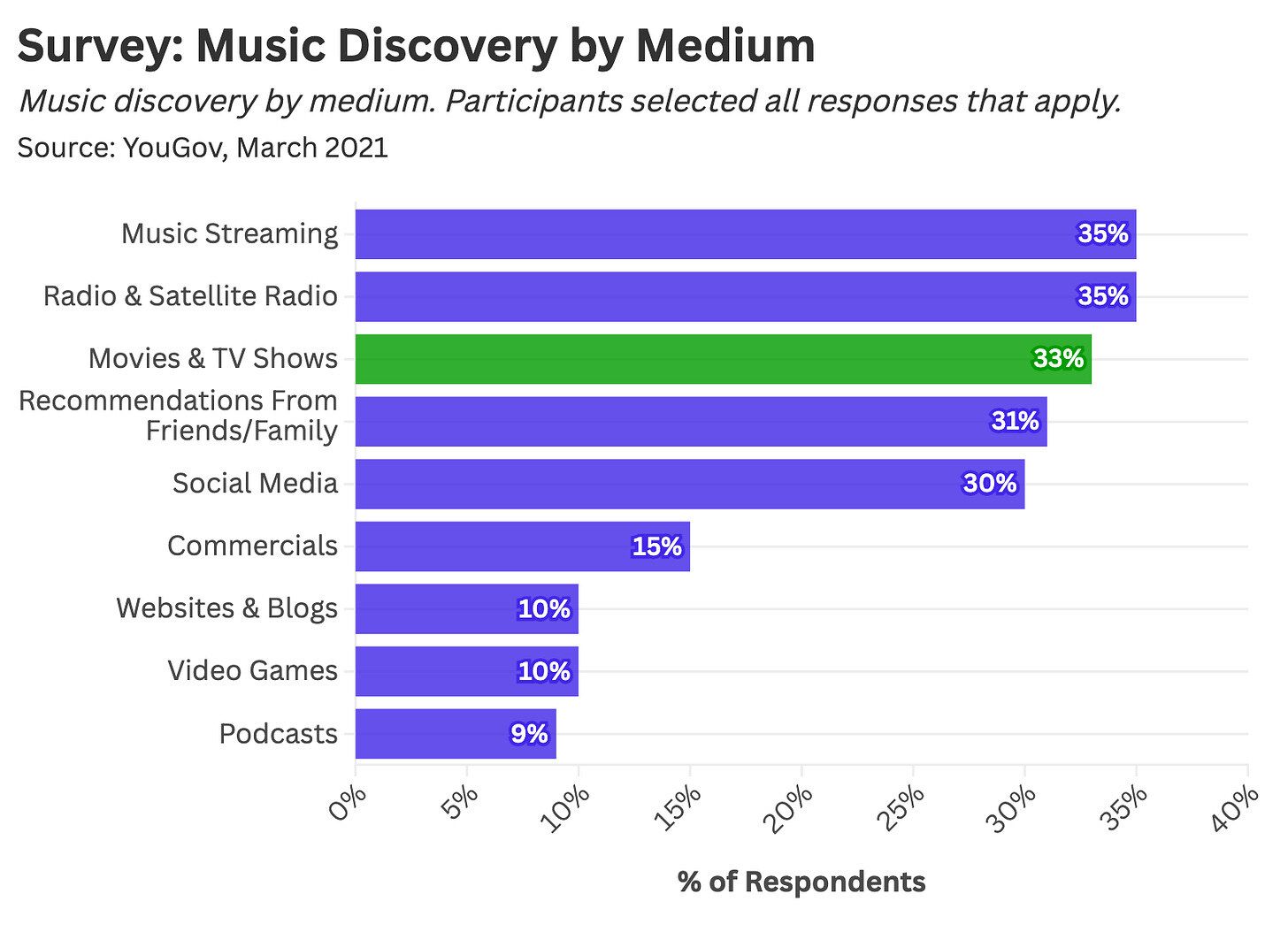

Yet movies and television still make use of pop music. A 2021 YouGov survey on song discovery found that 33% of listeners discover new tracks through television and movies.

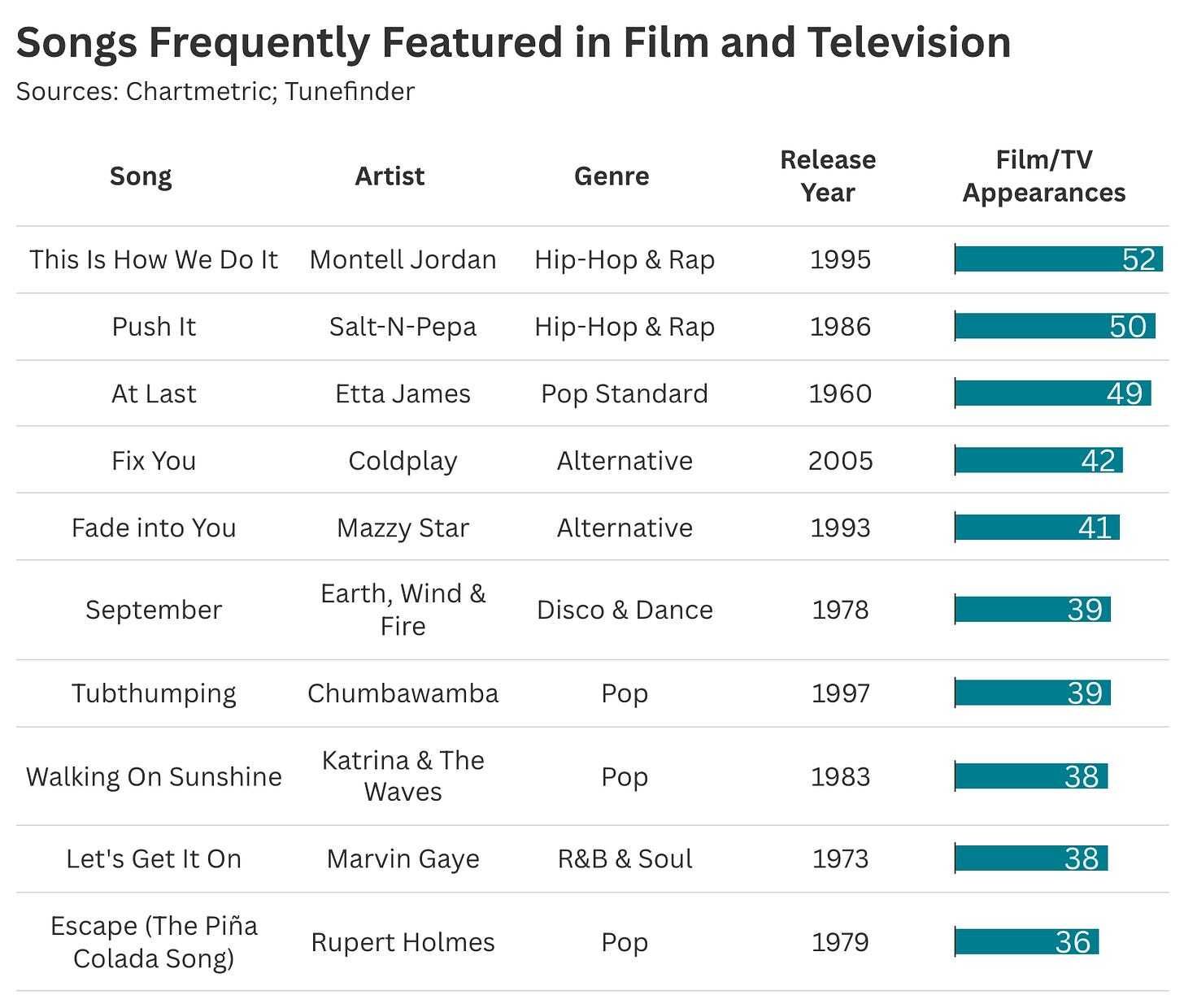

So what music are these viewers discovering? In short, they’re finding well-worn classics. Using media-citation data from Tunefinder, we see a familiar canon of iconic songs recurring throughout popular entertainment—led by Etta James’ “At Last” and Montell Jordan’s “This Is How We Do It.” Notably, the bulk of these data points come from contemporary media that’s looking backward, resurfacing tracks that are decades old.

Many of these tunes have longstanding associations with common storytelling tropes:

Hedonism, Partying, and Dancing: “This Is How We Do It,” “Push It,” and “September.”

Falling in Love, Dating, and Sex: “At Last,” “Fade Into You,” “Let’s Get It On,” and “Escape (Piña Colada Song).”

Getting Knocked Down and Getting Back Up Again: “Tubthumping.”

Ham-fisted Emotional Manipulation: “Fix You.”

If all this reads as reductive, well, that’s the point.

The upside of this audio meme-ing is longevity. Every slow-motion sequence featuring “At Last” introduces Etta James to a new cohort of listeners, quietly renewing her cultural relevance.

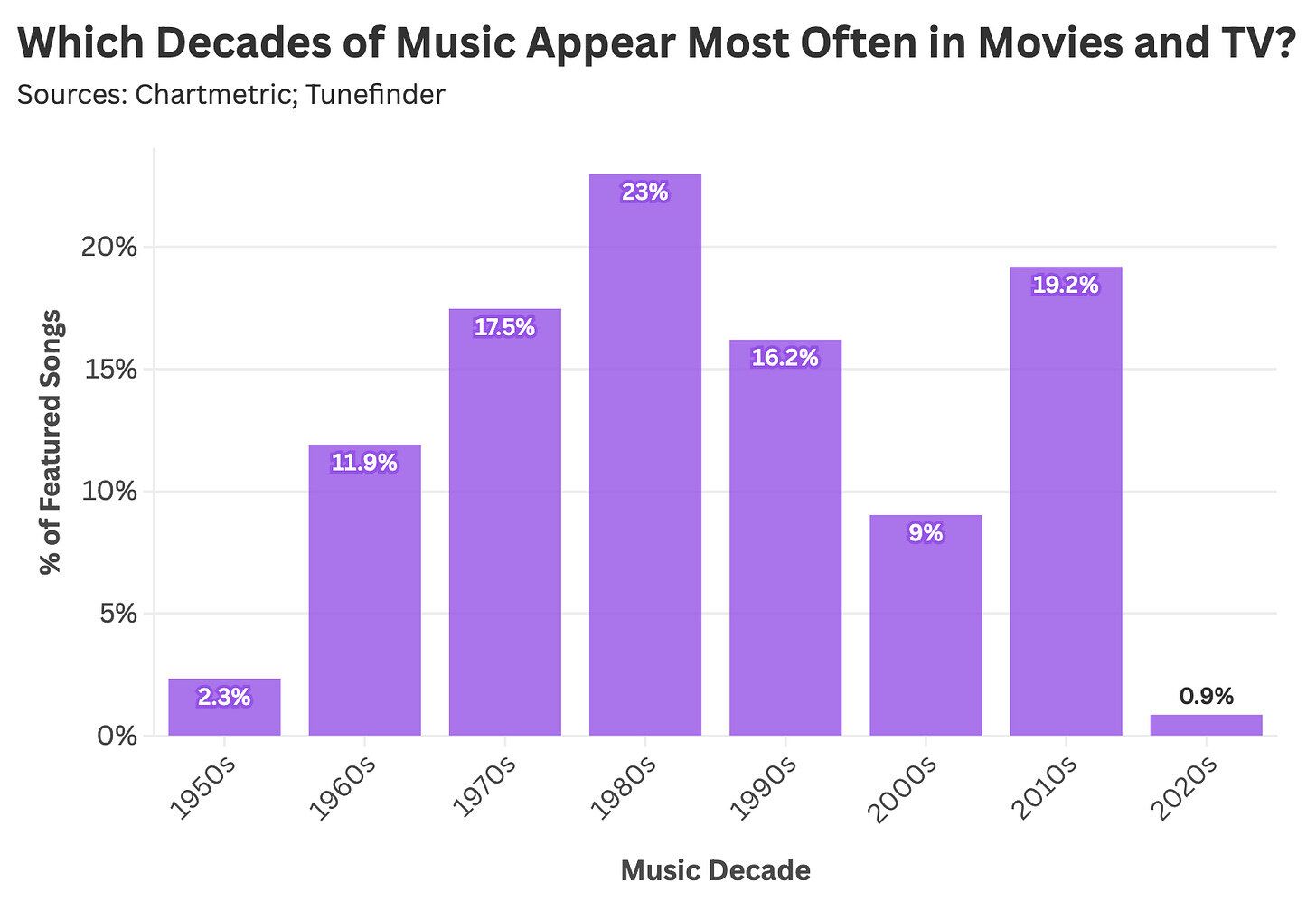

The industry’s turn toward thematically relevant classics is readily apparent in the data. According to our Tunefinder dataset, contemporary film and television disproportionately rely on tracks released before the 21st century, with a surprising concentration in the 1970s and 1980s.

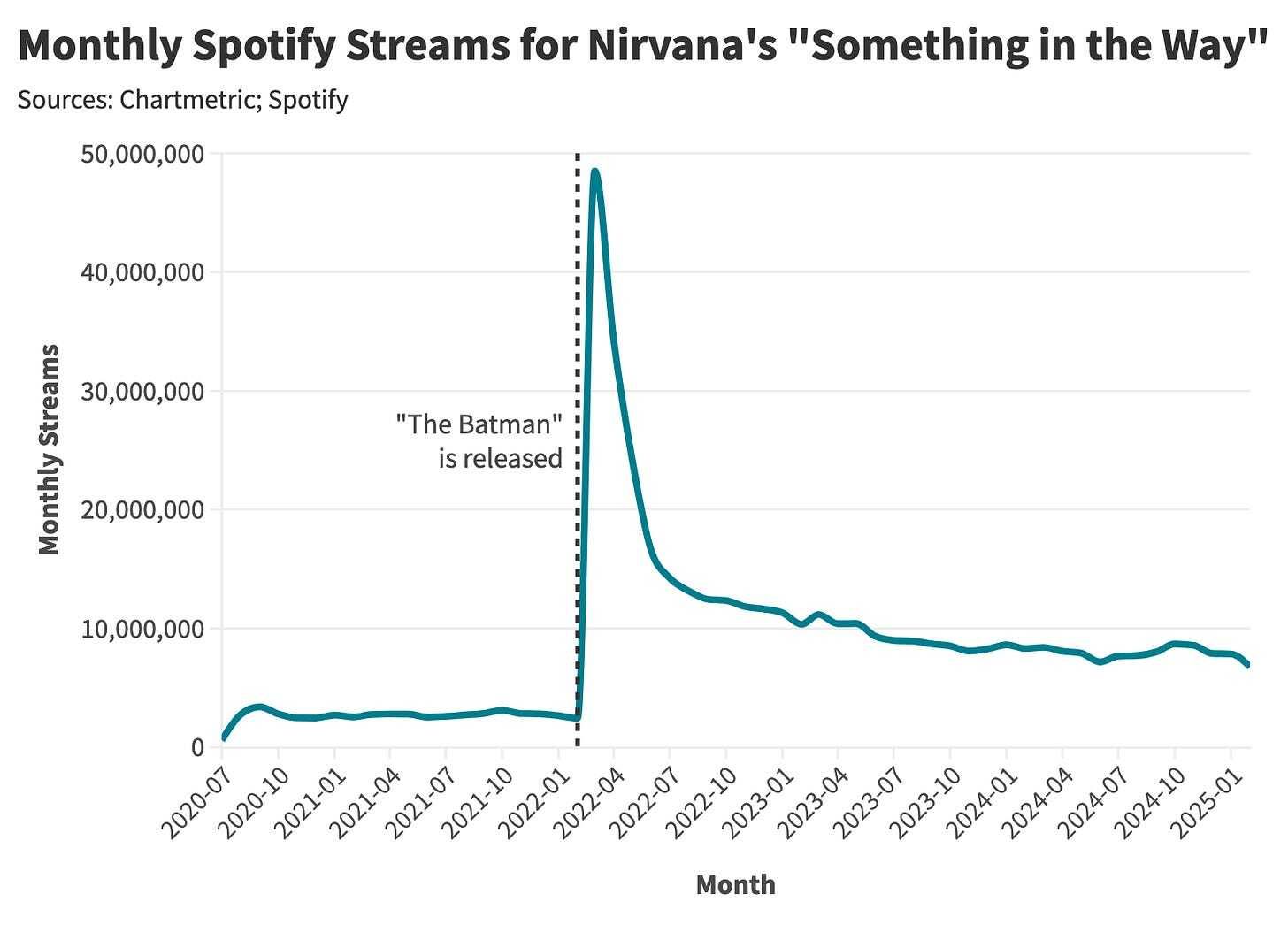

This dynamic has given rise to what I’ll call the Kate Bush Effect: the rediscovery of older staples through contemporary entertainment—à la Stranger Things’ revival of Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill.” We can see the same phenomenon at work with Nirvana’s “Something in the Way,” which received prominent placement in 2022’s The Batman. The film’s sizable audience triggered an immediate surge in streams, followed by an increased listenership baseline after the initial uptick.

It no longer makes sense for studios to commission an entire slate of original songs. Instead, they mine the archives, resurfacing beloved tracks that can be reheated like cultural leftovers. In the process, decades-old songs go viral—finding new, durable fandoms long after their initial moment.

Final Thoughts: The Curious Case of “Golden”

KPop Demon Hunters (2025). Credit: Netflix.

Many readers have probably maintained a single, persistent question while reading this piece: What about KPop Demon Hunters? Isn’t that a mega-hit soundtrack? To those people, I say: Well done, you are correct. Netflix’s KPop Demon Hunters has achieved an outsized cultural footprint reminiscent of Saturday Night Fever and Grease.

The curious case of KPop Demon Hunters—and its impending sequels—offers an instructive case study for the future of Hollywood soundtracks. Originally developed by Sony Pictures for a theatrical release, the film changed course in 2021 when Sony sold distribution rights to Netflix, opting for guaranteed revenue amid pandemic-era uncertainty. What followed is our current reality: the film became Netflix’s most-watched movie to date and has lingered in cultural imagination—with an afterlife that will be extended by Oscar recognition, including a surefire win for Best Animated Feature and Best Original Song. Just yesterday, I saw two young girls wearing shirts emblazoned with the name of the film’s fictional KPop group, a full seven months after the movie’s release. As many parents are fully aware: KPop Demon Hunters is going to be in our lives for a while.

The soundtrack’s ubiquity is the product of two competing—and highly volatile—economic models:

The Movie’s Development for Theatrical Exhibition: Sony reportedly invested $100 million to produce a big-budget animated feature with an original, pop-forward soundtrack, assuming a post-pandemic theatrical rebound would justify the expense. Put simply, the movie was produced according to an economic blueprint that is increasingly antiquated.

The Film’s Cultural Breakout on Streaming: Netflix’s global scale enabled KPop Demon Hunters and its music to reach an audience far larger than a conventional theatrical run might have supported. Streamers can afford to take chances on original films untethered to existing IP because the subscription model rewards breadth and experimentation—even niche successes—while simultaneously shifting risk away from expensive theatrical marketing campaigns.

Taken together, KPop Demon Hunters is a hybrid artifact: a classically conceived Hollywood musical blockbuster paired with a distribution strategy that reflects where risk-taking currently lives in the entertainment industry. This tension raises an intriguing question about the future of big-budget soundtracks: was this movie a miraculous one-off, or a glimpse of what comes next? Can theaters once again support soundtrack-driven hits at scale, or will streamers invest in music-forward films to manufacture another monocultural smash?

What’s clear is that the music-to-movie pipeline is no longer well-oiled or predictable. Gone are the days when a composer like James Horner could stumble into a chart-topping classic like “My Heart Will Go On” through movie magic, Céline Dion, a director’s reluctant acceptance, and happenstance.

Want to promote your data tool or media publication to Stat Significant’s 23,800 readers? Email [email protected]

Need help with a data problem? Book a free data consultation

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you want to chat about a data project.

Like movies? Follow me on Letterboxd