- Stat Significant

- Posts

- When Did Popular Music Become Standardized? A Statistical Analysis

When Did Popular Music Become Standardized? A Statistical Analysis

When did popular songs begin sounding the same?

Katy Perry’s “Roar” Music Video. Credit: Capitol Records.

Intro: The Progress and Peril of Music Distribution

Before there were Napster, iTunes and Spotify, there was Thomas Edison's phonograph. In 1877, Edison introduced the phonograph to record messages for business communications. However, the music industry quickly embraced the technology, with penny arcades installing phonographs to play pre-recorded songs for their customers. Music was no longer confined to upscale performance halls and social gatherings—music was now a democratized commodity accessible to all.

For most, the advent of music recording and distribution allowed for increased cultural exposure, untethering the art form from live performance—but not all were pleased. Renowned American composer John Phillips Souza, a man who looked like a cross between Colonel Mustard and Teddy Roosevelt, believed that the availability of recorded music would discourage people from attending live shows and ultimately erode standards for musical craftsmanship. He famously stated, "These talking machines are going to ruin the artistic development of music in this country," prophesizing that listeners would embrace the passive consumption of derivative "canned music."

John Phillips Souza. Credit: Wikipedia.

Culture critic Theodore Adorno complained that mass-distributed music led to increasing "standardization," lamenting that popular works were settling upon "verse-chorus-verse-chorus" patterns and other conventions in which "nothing fundamentally novel [would] be introduced." Thankfully, neither of these men would live to see the wonders of Spotify, Napster, or Nickelback.

Fast forward to 2013, when Katy Perry's "Roar" and Sara Bareilles' "Brave," released four months apart, drew immediate comparisons for their strikingly similar melodies and themes of empowerment. The bizarre coincidence generated significant media coverage, with several stories focusing on their near-identical chord progression and tempo. Numerous YouTubers created mashups of the two songs to highlight their resemblance (and these videos are quite effective).

The entire episode sparked debates on the originality of popular songs. Was this a one-off incident of (accidental) mimicry, or was this unintentional mimicry emblematic of pop music's standardization? Had the prophecies of Souza and Adorno come true? Is popular music a templatized commodity marked by minimal sonic diversity, and if so, when did the industry move toward uniformity?

So today, we'll explore the diminishing variety offered by popular music and the broader trends that spurred increasing standardization in song composition.

Methodology: How to Quantify Music Standardization

Our goal is to track changes in composition variability for popular music. We'll define popular songs as works listed on "The Billboard Hot 100" charts and utilize Spotify's database of song attributes to track changes in music design.

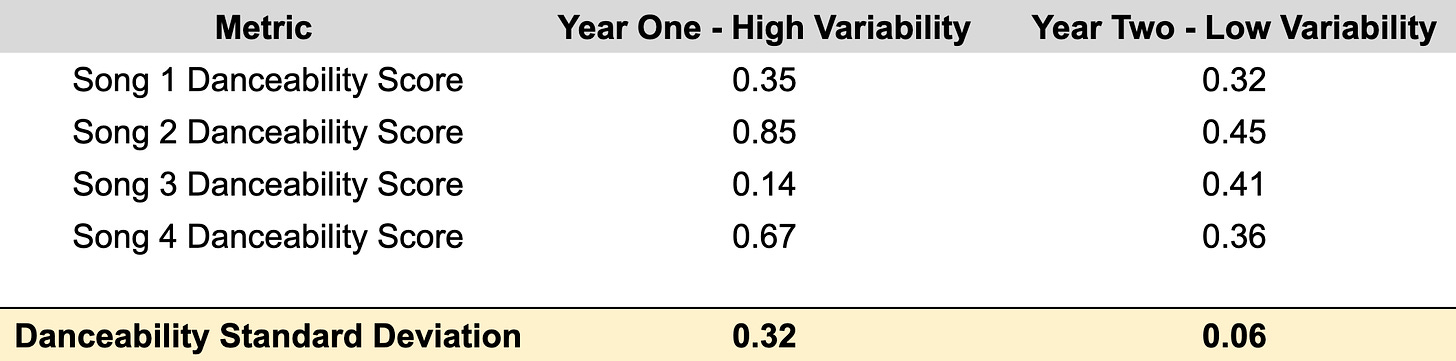

We'll quantify composition diversity by tracking variance across a given year's Billboard-charting songs. Consider Spotify's danceability metric for two different years—one low variability and one high variability. Year One showcases a diverse set of tracks with widely varying danceability scores, while Year Two has a tighter range of danceability figures.

Year One has a higher standard deviation and, therefore, demonstrates more variety when it comes to danceability. In contrast, songs from Year Two showcase greater uniformity for this metric.

We'll perform this analysis for various Spotify attributes for songs released between 1957 and 2021.

Are Song Runtimes Becoming Standardized?

In the late 1960s, the 12-inch LP record overtook the 78 RPM design as the go-to format for singles, expanding average music capacity from 4–5 minutes per vinyl side to 7–12 minutes. This improvement in vinyl design was among numerous data storage innovations during the 1950s and 1960s.

Boston Pops conductor demonstrating a new Vinyl format. Credit: Wikipedia.

Before the introduction of longer-playing formats such as the 33 RPM and 12-inch LP, the length of songs was limited by storage constraints. In the late 1960s, storage capacity grew to 22 minutes per side of music, enabling artists to create lengthier works, often found on concept albums, and to include more tracks per release.

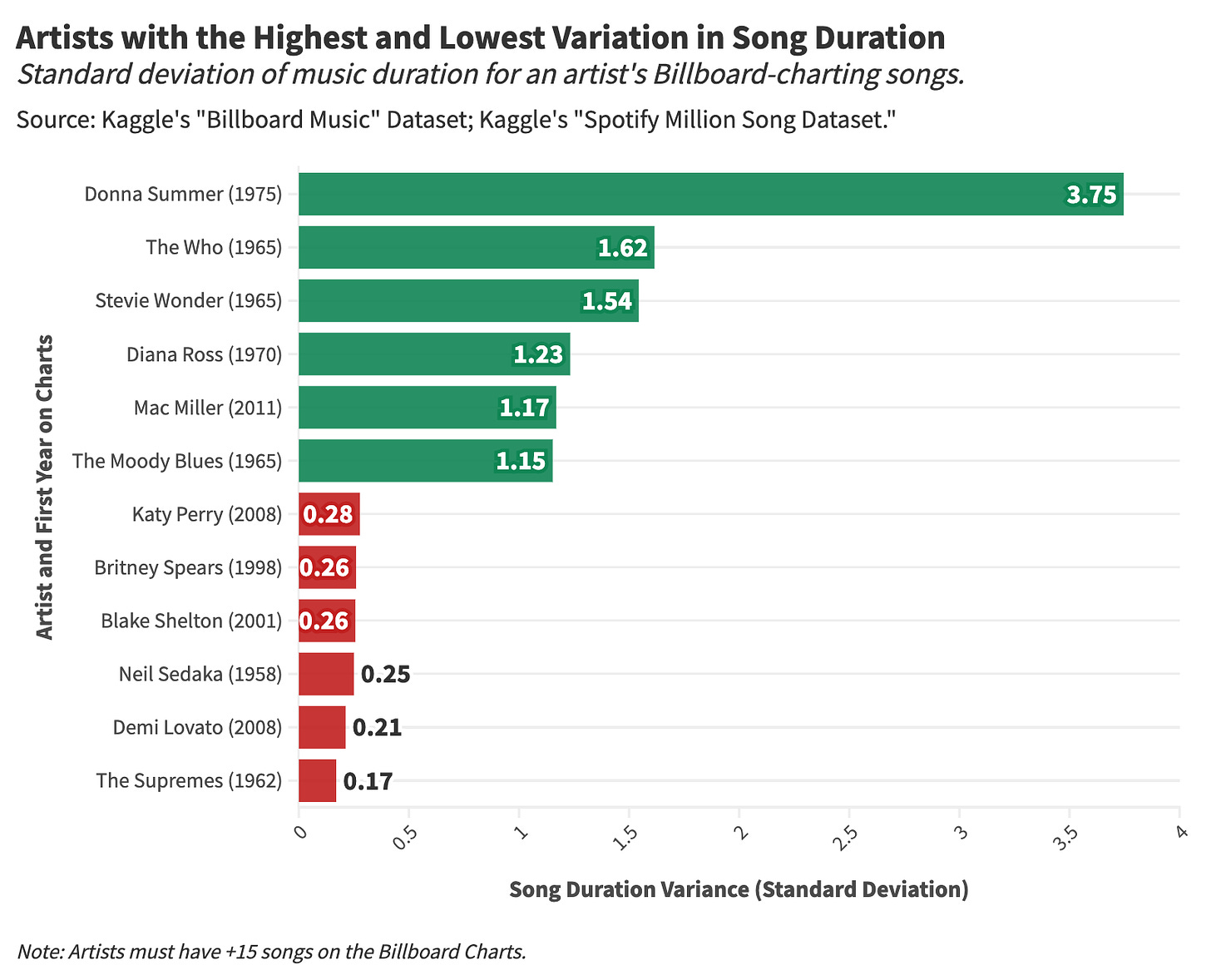

As a result, we observe minimal variation in song duration for early Billboard hits, followed by a substantial spike in runtime variability in the 1960s and 1970s. This period was marked by long-running rock anthems and disco dance tracks, including "Free Bird," "American Pie," "Love to Love You Baby," and "Disco Inferno."

This extreme temporal experimentation would fade in the early 1980s as disco died, rock's cultural supremacy waned, and songs were increasingly optimized for music videos. There was still some variation, but a three-minute guitar solo or instrumental dance break did not play as well on MTV, limiting the commercial viability of longer tracks.

We then observe a substantial decline in runtime variability in the late 90s and early 2000s spurred by two paradigmatic shifts in music distribution. First, the introduction of iTunes and streaming led to a decoupling of songs and albums. Artists began focusing on the commercial maximization of individual tracks over cohesive album concepts. Second, streaming services typically pay per play, rewarding artists for the number of listens as opposed to total listening time. Streaming ten 31-second tracks pays more than a single stream of a 310-second song. Artists and record labels responded to this new paradigm with shorter song runtimes, as there was now a significant disincentive to experiment with longer duration. Thus, popular music became uniformly shorter.

When we look at artists with the highest and lowest runtime variability amongst their Billboard-charting hits, we find greater duration diversity for rock bands and disco acts like The Who, The Moody Blues, Donna Summer, and Diana Ross. Meanwhile, we observe lesser runtime variation for 1950s and 2000s pop acts like Neil Sedaka, Katy Perry, Britney Spears, and Demi Lovato.

Improbably, the diversity of runtimes in popular music has performed a 180 over Billboard's lifetime. Somehow, limitless cloud storage and infinite consumer choice have yielded a duration uniformity comparable to the 1950s and the days of 78 RPM records.

Need Help with Your Data Career?

Well, you’re in luck! Stat Significant now offers data science career mentorship. Gain personalized guidance, insights, and the practical experience needed to navigate the complexities of a data science career. Accelerate your professional growth or career change with one-on-one mentorship from a senior data scientist.

Are Song Vibes Becoming Standardized?

Next, we’ll examine elements of song composition related to emotional resonance, including:

Danceability: How suitable a track is for dancing based on a combination of musical elements.

Energy: Representing a perceptual measure of intensity and activity, with energetic tracks feeling fast, loud, and noisy.

Positivity: The musical positiveness conveyed by a track.

All three variables are rated on a scale of 0 to 1 (i.e., a song can be given an energy rating of 0.45, for example).

Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark” Music Video. Credit: Columbia Records.

Since the early 1990s, popular music has experienced a noticeable dip in variety for energy and danceability, as well as a modest decrease in positivity variance.

This decline in variability is concurrent with an overall rise in average danceability and energy levels as well as a decline in average song positivity levels. Said differently, popular music is higher-energy, more dance-y, and less positive—with less sonic diversity as measured by these attributes. A few theories on what spurred these trends:

The Importance of Live Music: The digitization of music distribution offers consumers abundant music content in return for a tidy and affordable subscription fee. In response, music acts shifted their profit centers from record sales to live performances. And what do people like to do at music shows? Dance (while wearing a flower crown)! Hip-hop, rap, and electronic music are cheap to produce and are amongst the most dance-able genres.

Industrialization of Music Production: Over the last thirty years, song creation has grown increasingly computerized, with major studios adapting digital workflows and programs like Logic and GarageBand democratizing prosumer production. Artists have slowly converged on a homogenetic sound for hip-hop, rap, and electronic music, with music technology capable of producing optimally dance-able beats.

The Rise of Hip-hop and Rap: Hip-hop and rap dominate modern music culture, a genre Spotify regularly labels as high danceability, high energy, and lower positivity.

Modernization of Music Subject Matter: At first pass, one might think that uniform declines in song positivity speak to some sort of music nihilism. Instead, my hot take is that modern music better reflects our complicated everyday experiences. Genres like rap and hip-hop often examine difficult subject matter, with taboo topics like sex, violence, political subjugation, and mental health regularly depicted in popular music. Decades ago, explicit representations of these themes were a rarity in pop music.

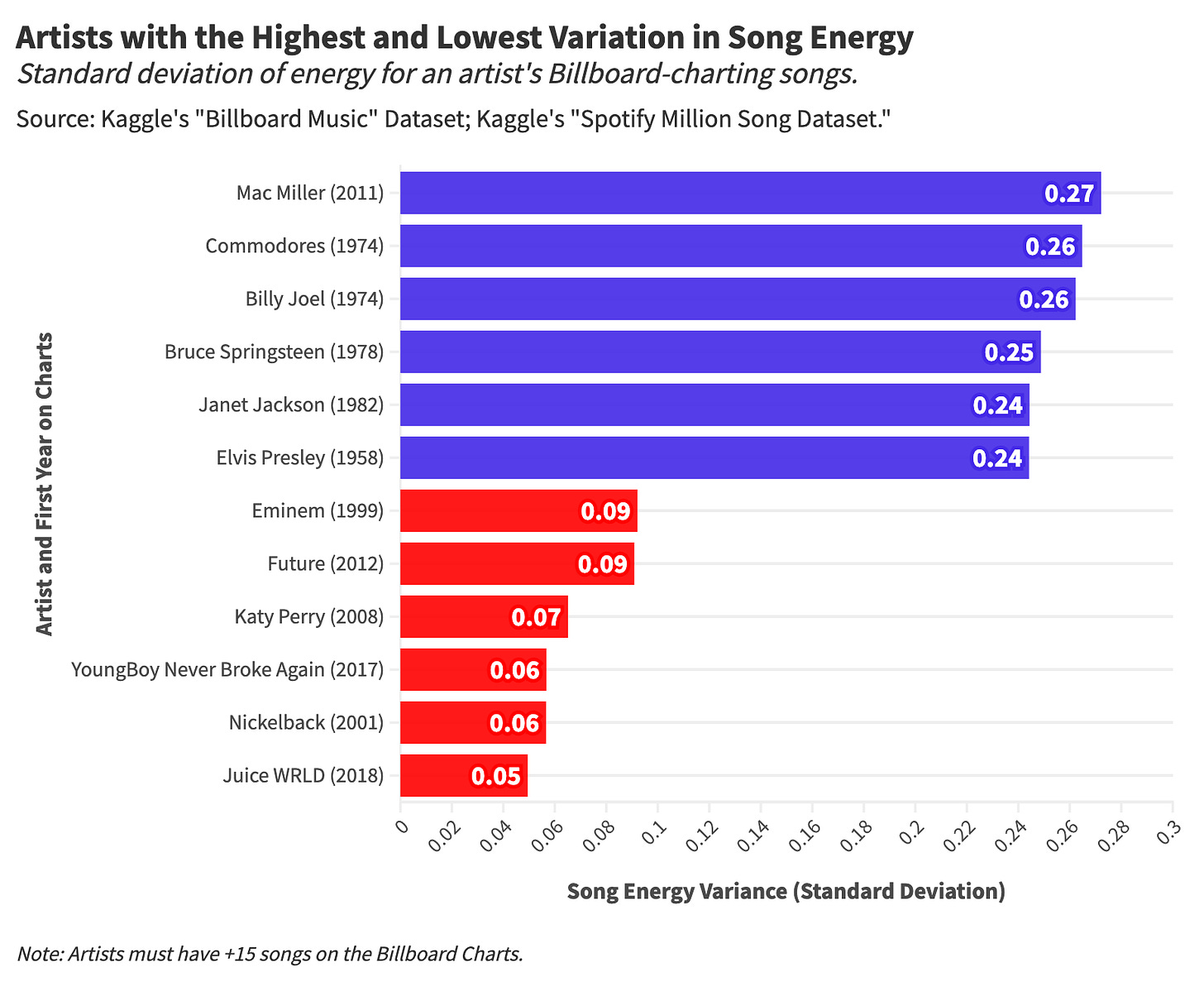

When analyzing artists based on song energy levels, we find that soft rock performers such as Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, and Elvis Presley exhibit greater variety—these artists have produced both fast-paced anthems and slower ballads. Amongst the artists with low energy variability, we observe pop and rap acts like Future, Katy Perry, and Juice WRL—artists with a prototypical style and pace.

You've also got to love that Nickelback appears in the low variety category—proof that this band is quantifiably formulaic.

Is Music Instrumentation Becoming Standardized?

Spotify defines speechiness as the "presence of spoken words in a track (often absent instrumentals)" and describes instrumentalness as "[predicting] whether a track contains no vocals." Both metrics rate songs on a scale of 0 to 1, with all ratings appearing as decimals within this range.

Variance in instrumentalness has declined over the last fifty years while speechiness variability has risen. Said differently, popular music increasingly highlights vocals over instrumentals.

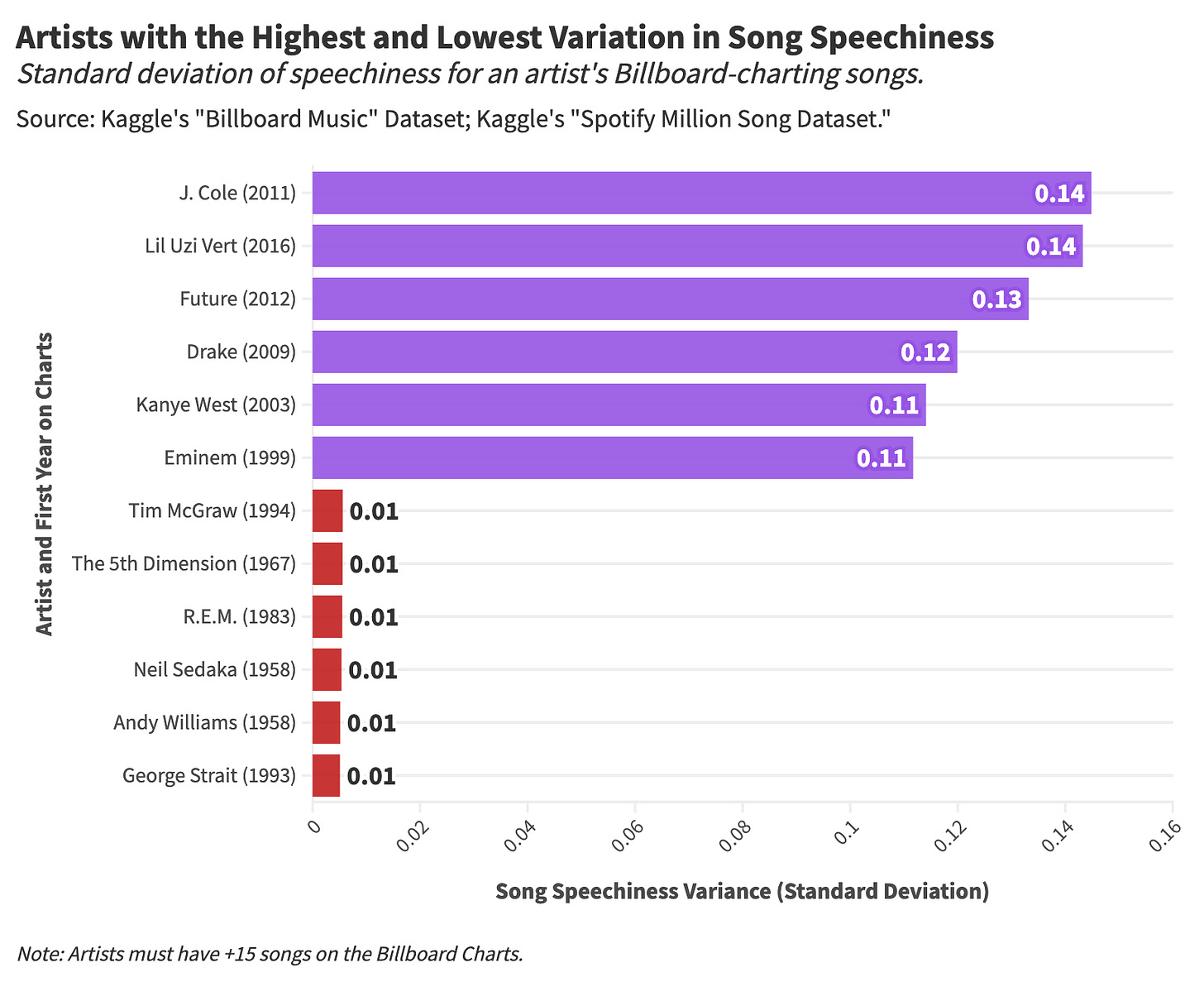

These trends underscore rock's declining influence, with popular music featuring fewer instrumental solos. Meanwhile, our observed rise in speechiness variability emphasizes rap's growing cultural dominance. Zeroing in on artists with high and low speechiness variety, we find significant variance in the works of rappers like Drake, Eminem, and Future and less variety for country acts like Tim McGraw, Andy Williams, and George Strait.

Ultimately, an artist's words are the most crucial instrument in rap music. With or without instrumentals, artists like Eminem and J. Cole can still shine. In a sense, the lyrical stylings of Drake and Future have replaced the famed guitar work of Eddie Van Halen, Carlos Santana, and Slash.

Final Thoughts: The Wonderful Sameness of Collective Culture

The UK’s Glastonbury Music Festival. Credit: Wikipedia.

It's tempting to paint technological progress as the enemy of artistic expression, to adopt the critiques of Adorno and John Phillips Souza. Through this lens, every innovation in music distribution degrades artistic craftsmanship. According to this line of thought, the streaming age has seen popular songs morph into templatized commodities that are passively consumed through Spotify playlists like "scarf season" and "make-out jams." However, such criticism overlooks the benefits of collective culture and the connections derived through works of art.

A few years ago, I was in a crowded bar in Tel Aviv when a DJ played Electronic Light Orchestra's "Mr. Blue Sky." Nearly all bar patrons rushed onto the dance floor, jumping up and down and singing along in unison. Sandwiched within this mob, I screamed along, sharing a moment of euphoric connection through mass-distributed media.

Think about how far "Mr. Blue Sky" had to travel to arrive at this bar in Tel Aviv in the 2020s:

A British band recorded and released the song in 1977, eventually hitting 35 on the Billboard Charts—earning this work global recognition.

The song was then kept alive within popular imagination through various music mediums, including vinyl, cassette, CD, iTunes, and streaming.

These distribution channels propelled the song to perpetual global relevance over a period of fifty years to the point where a bar full of Israelis knew every lyric.

Without Edison's phonograph and everything spawned in its wake, "Mr. Blue Sky" would not have made it into the hearts and minds of these Tel Aviv-ian bar-dwellers. It's easy to lament the secondary effects of mass distribution, yet such industrial progress allows for greater artistic exposure and widespread cultural ties.

Imagine Luddites had somehow stalled the phonograph's adoption and that we live in a world without industrial-scale music distribution. Maybe you'd be okay with this counterfactual, attending elitist shindigs where you can listen to symphonies and rhapsodize on your high-mindedness. All that sounds great, but it probably doesn't beat the collective thrill of a wedding dance floor grooving to Earth, Wind & Fire's "September."

I like having my favorite music readily accessible. I like listening to music while I work. I enjoy singing along to Taylor Swift jams and lampooning Nickelback songs. I love karaoke—perhaps one of my all-time favorite activities. If the trade-off for these experiences is that popular music is slightly more formulaic, then so be it.

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]