- Stat Significant

- Posts

- Are Movies Better When We Watch Them in Theaters? A Statistical Analysis

Are Movies Better When We Watch Them in Theaters? A Statistical Analysis

Do we like a movie more if we watch it in theaters?

Avatar (2009). Credit: 20th Century Studios.

Intro: Does Avatar Matter?

Avatar was marketed as a revolutionary cinematic experience capable of transporting audiences to the alien world of Pandora. The film marked James Cameron's return to feature filmmaking more than a decade after the monumental success of Titanic, with media coverage emphasizing Cameron's development of state-of-the-art visual effects and the film's considerable $237M budget. As Avatar hype reached a fever pitch, it became clear that this film was an unprecedented cinematic event with an urgency that demanded it be seen in theaters (possibly multiple times). Sure enough, Avatar proved a box office phenomenon, surpassing Titanic to become the highest-grossing movie of all time.

And then, suddenly, the movie disappeared—or rather, its cultural significance faded relative to its remarkable box office. Years after Avatar's release, Forbes declared, "Five Years Ago, Avatar Grossed $2.7 Billion but Left No Pop Culture Footprint." In 2016, Buzzfeed created a quiz entitled, "Do You Remember Anything at All About Avatar?" challenging readers to recall basic details like the lead character's name (Jake Sully) or the actor who played Jake Sully (Sam Worthington, of course). Somehow, Avatar's commercial success had not translated into cultural longevity. Was this movie's short-lived preeminence a mass delusion, or was this film significantly more entertaining in theaters than at home?

Indeed, Avatar is an example of a movie that is best enjoyed on the big screen (whilst wearing 3D glasses). Unfortunately, few films can match the public fascination generated by Avatar's theatrical run (or the hype surrounding its sequel released in 2023). As streaming services and prestige TV content have proliferated, the movie industry has struggled to lure audiences to theaters. Why leave your home (and Netflix) to pay $20 for a single piece of content when you could watch hundreds of shows for $15 a month?

The film industry has countered this trend by emphasizing the indelibility of moviegoing, as highlighted by AMC's Nicole Kidman advertisement, which (bizarrely) promotes movie patronage to people already at the movies. Such fanfare begs fundamental questions on the value of theatrical exhibition. Does the magic of the movies actually exist? Do audiences like movies more when seen in theaters?

Are Movies Better When We Watch Them in Theaters?

There was once a time when moviegoing provided entertainment experiences that were impossible to replicate outside of theaters. Enthusiastic fans saw blockbusters like Titanic, Star Wars, and Jaws multiple times, reveling in the audiovisual spectacle offered by 35mm film and Dolby Sound. This novelty would wane throughout the 2010s as the AV gap between theatrical exhibition and home entertainment narrowed.

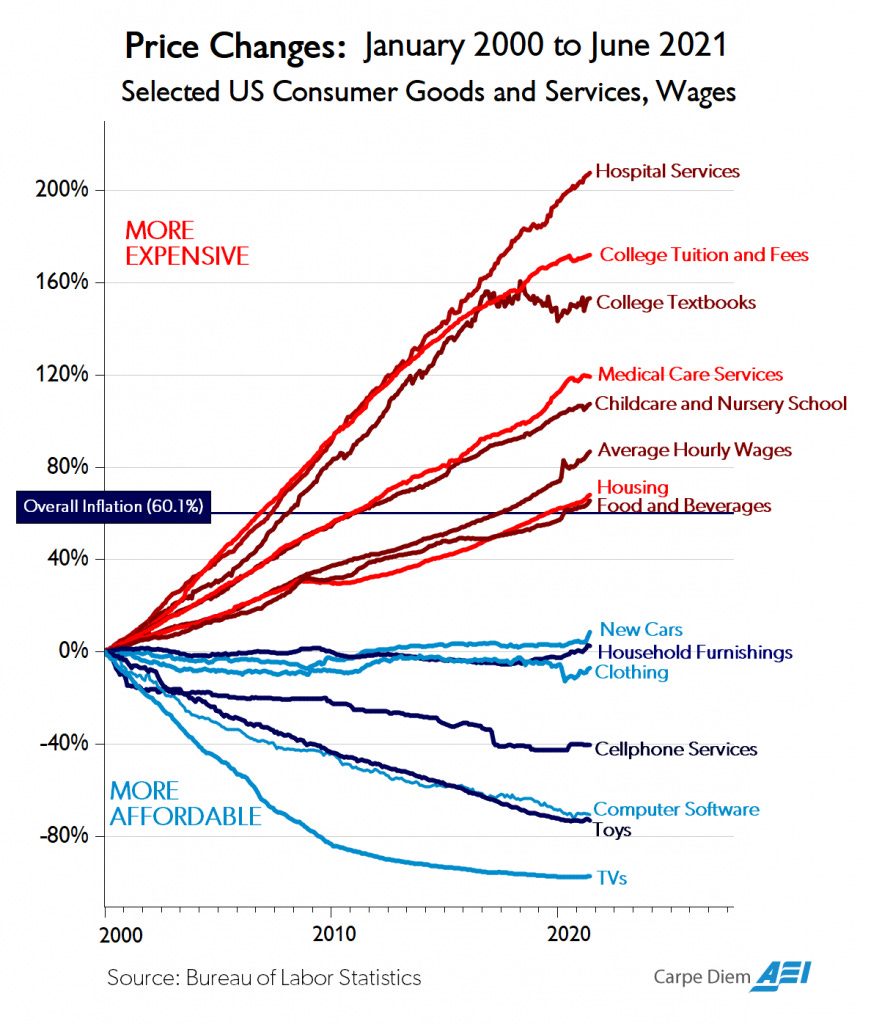

High-quality television products became increasingly affordable, while prestige television content flooded the market amidst Hollywood's streaming wars. In fact, television prices decreased at an unprecedented rate compared to other goods and services.

Source: Carpe Diem AEI.

You could watch content in the privacy of your home and see something spectacular (in 4k!) without ever having to brave a Nicole Kidman advertisement—you could pay less and watch more. But was something lost within this paradigm shift? Does the ritual of moviegoing and the enhanced audiovisual experience provided by theatrical exhibition heighten entertainment value?

To tackle this question, we'll use data from a site called MovieLens, a virtual community that collects movie ratings and reviews and then uses this data to recommend films to its users. The MovieLens dataset offers a treasure trove of over 20 million movie ratings collected between 1995 and 2015, allowing us to pinpoint differences in viewer reaction between theatrical exhibition and home viewing. When we analyze average monthly star ratings in the months after a film's debut, we observe higher scores during a project's theatrical run, followed by a ratings decrease when that work moves to streaming and home video.

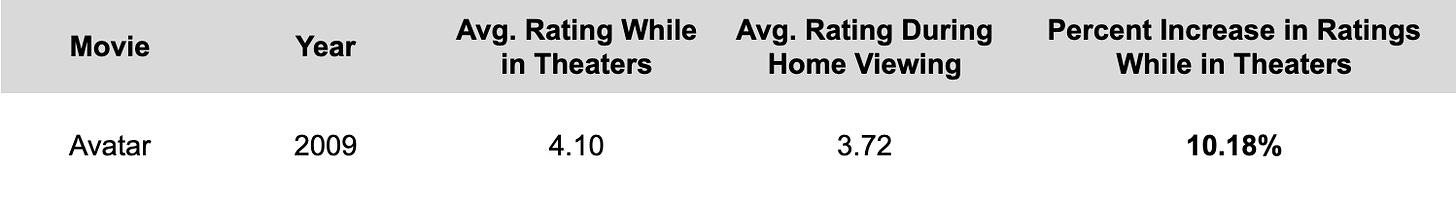

This trend holds when comparing a single movie's initial ratings to those posted once that work has exited theaters—with 84% of films in the MovieLens dataset receiving higher scores while in cinemas. Overall, online ratings increase anywhere between 2% and 5% during theatrical exhibition (depending on how we measure this phenomenon). Unsurprisingly, MovieLens reviews for Avatar scored 10% higher while the film was in theaters—a win for those claiming its cultural staying power is inconsistent with its monumental box office.

There is a possibility that this spike in viewer satisfaction is the product of self-selection—that diehard fans predisposed to love a movie insist upon seeing that work in theaters. If this is the case, it still speaks to the value of theatrical exhibition. Marvel movies, A24 films, and Star Wars prequels draw audiences to theaters—something about these movies is best enjoyed on a big screen in a communal setting.

Some films have diminished appeal when viewed at home, while others could just as easily be adapted into eight-part miniseries with little change in premise. Can we detect a difference in viewer appraisal based on storytelling conventions? Are certain movies (quantifiably) more enjoyable in theaters, or do all works experience a uniform uptick in viewer ratings during cinematic exhibition?

Need Help with a Data Project?

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data science and data journalism consulting services. Reach out if you’d like to learn more.

Email [email protected]

Which Films Are Best Enjoyed in Theaters?

The summer of 2023 ended the reign of comic book movies at the box office. In the first half of the year, Marvel's Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania and DC's The Flash both bombed in spectacular fashion. Media outlets covered these releases by eulogizing superhero cinema, with The Ringer remarking, "The Flash Is the Depressing Culmination of the Great IP Experiment" and Rolling Stone quipping, "Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania Feels Like the MCU Has Lost Its Way." Superhero fare was no longer a sure thing.

Months later, the Barbenheimer phenomenon became a massive cultural event, with these two mismatched movies pulling in a collective $2.4B in global ticket sales.

Source: The Financial Times.

For so long, adaptations of superhero fare provided a clear-cut formula for event-izing a movie. Suddenly, the entertainment industry fell into crisis. Was the franchise model faltering? Was serendipitous counterprogramming the new way (and could studios manufacture another Barbenheimer)?

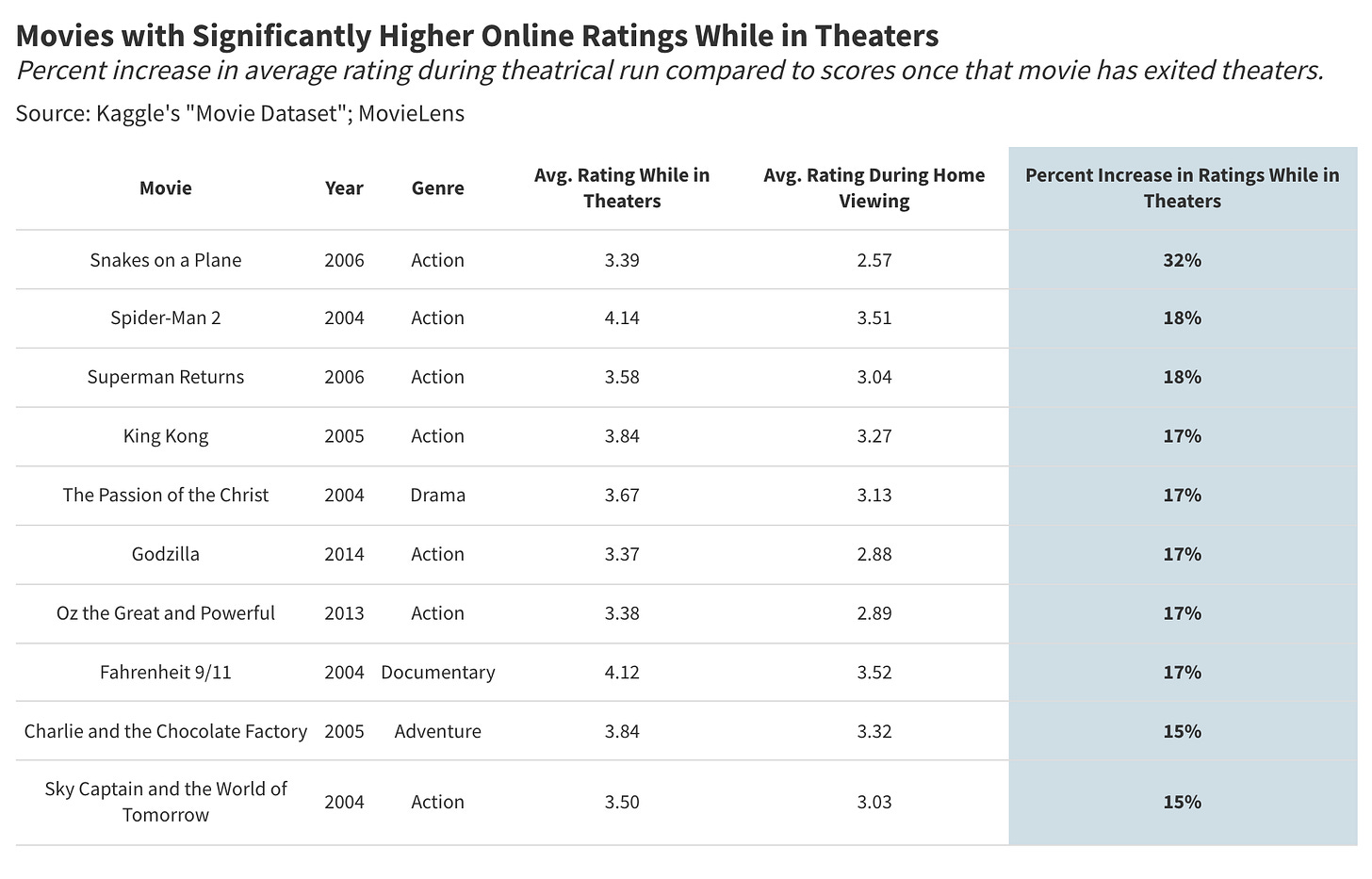

Although the reliability of franchise IP has weakened, Hollywood's strategy is (regrettably) based on sound economic thought—big-budget intellectual property performs well in theaters. When we look at the movies with significantly higher online ratings during theatrical exhibition, we find a collection of action films (mostly derived from IP) and arguably the two most controversial movies of the 2000s.

I was young when Passion of the Christ and Fahrenheit 9/11 debuted, but I remember the adults around me being especially grumpy about these movies.

Credit: Lionsgate.

At the time of their premiere, these films felt essential to American discourse—a factor that potentially galvanized audience appraisal in the short term. These projects are likely less impactful once you strip away the sociopolitical context surrounding their theatrical run.

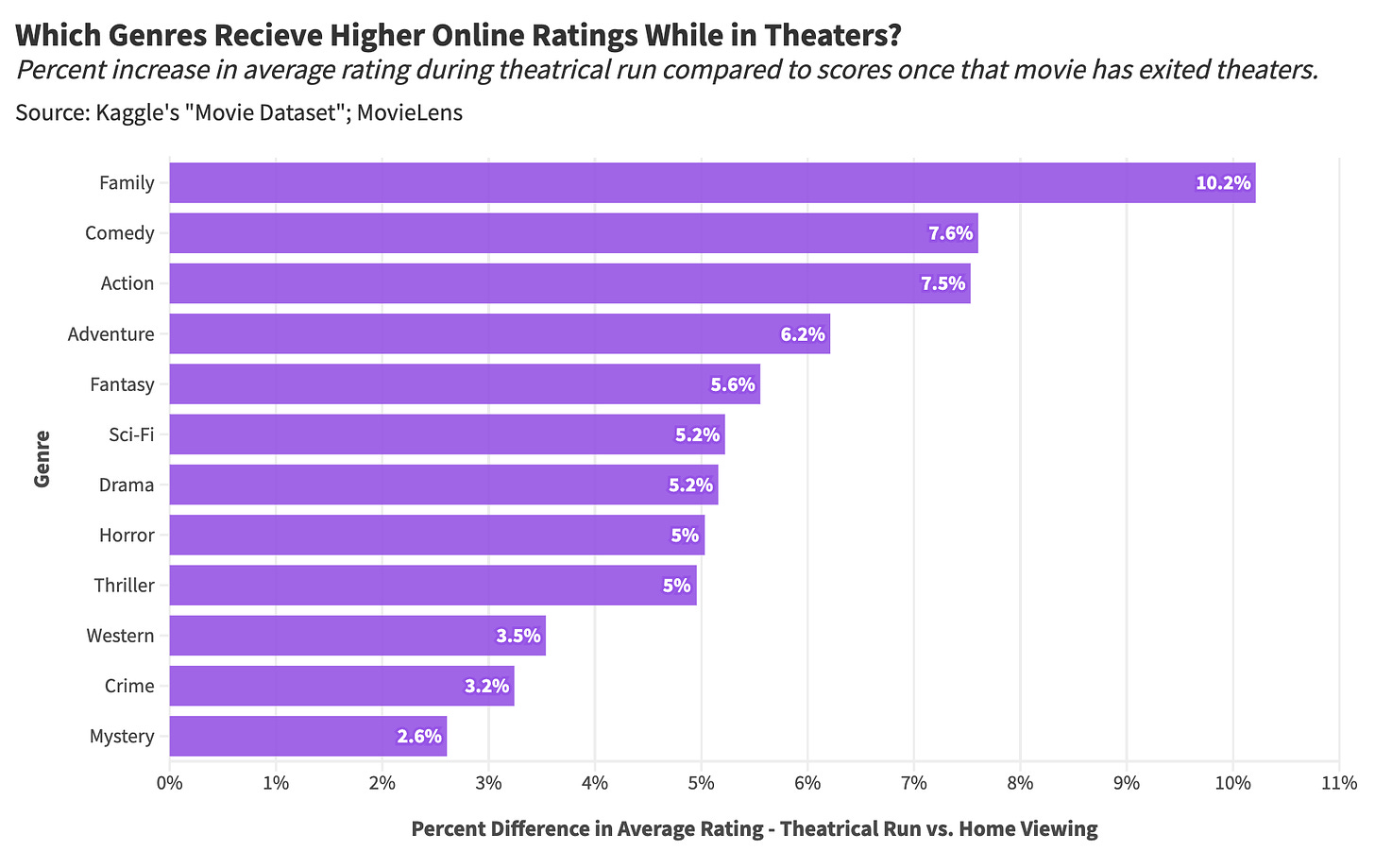

Unsurprisingly, when we examine the difference between short-term and long-term ratings by genre, we find that action and adventure movies score higher in theaters, likely due to audiences better appreciating their grandeur on the big screen.

Somewhat surprisingly, comedies experience increased ratings during theatrical exhibition—perhaps there is added value to laughing as part of a crowd. Overall, the most significant spike in ratings belongs to the family film genre. My best guess is that these elevated scores reflect the big screen's ability to capture children’s attention for prolonged periods (effectively babysitting those children).

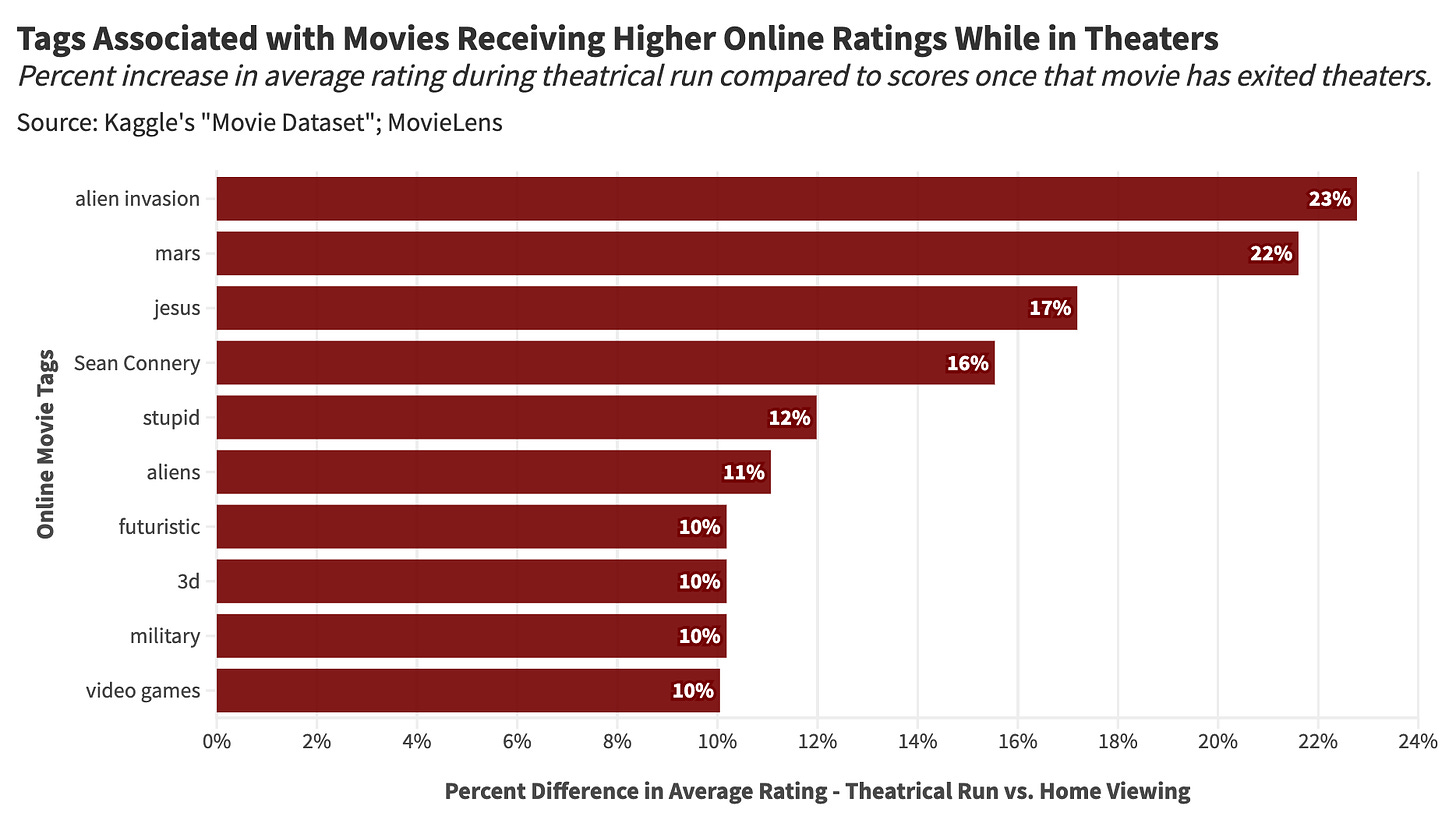

If we want to go deeper than genre, we can investigate the keywords associated with movies that receive higher ratings in theaters. Fortunately, MovieLens encourages viewers to tag films with details of story, cast, setting, and technique, such as "3D," "Africa," "Bill Murray," "violent," "whimsical," and more. Examining theatrical ratings uplift by tag, we observe increased scores associated with story elements related to the science fiction and action genres.

Using these tags, we can perfectly optimize a film for cinematic exhibition (but not home viewing). All we need to do is produce a 3D alien invasion movie set in the future based on a video game, making reference to Jesus and starring an AI-revived Sean Connery. This film would delight audiences in cinemas while generating mixed reception when viewed at home.

Final Thoughts: What's Cinematic?

Masters of the Air (2024). Credit: Apple TV.

This past month, I watched Apple TV's Masters of the Air, a 9-part miniseries on the exploits of WWII airmen (the show was pitched as "Band of Brothers but with planes"). The series spared no expense in its production, taking three years to create and costing between $250 million and $300 million to produce. Masters of the Air employed state-of-the-art flight simulation technology, replica B-17 planes, and construction of WWII barracks (to scale).

As I watched this show on my normal-sized TV and later on my iPhone mid-flight, I was struck by the needless excess of this program. Why spend so much money and time making something that could be consumed while multitasking on Instagram or amidst the screams of a child on my flight? Why spend $300M on disposable content?

One of the hallmarks of prestige television is the medium's adoption of cinematic storytelling conventions—anti-heroes, high-def camera work, and fanciful AV effects. The rise of prestige TV has coincided with the serialization of mainstream movies, which focus on developing characters and plots across multiple installments. Such convergence has muddied our conception of the cinematic, as it's become increasingly difficult to comprehend which medium best supports a given piece of content. Would Maestro and Masters of the Air be best received on the big screen? Would the MCU function better as a series of shorter installments on Disney+?

And then there's the economics of moviegoing. Sure, there is a 2% to 5% uplift in movie enjoyment when viewed in theaters, but what's the monetary value of increased amusement? Is this 2% to 5% uptick in entertainment value worth leaving your house, driving somewhere, paying $20 per ticket, watching 25 minutes of trailers, and receiving a functionally pointless thank you from Nicole Kidman for entering a theater? For me, the answer is yes—this incremental 2% to 5% means the world to me. To others, this excess enjoyment may not be worth the hassle—unless it involves the Avatar franchise and the trials and tribulations of Jake Sully (who is the lead character in Avatar, in case you've already forgotten).

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]