- Stat Significant

- Posts

- How Streaming Elevated (and Ruined) Documentaries: A Statistical Analysis

How Streaming Elevated (and Ruined) Documentaries: A Statistical Analysis

Unpacking streaming's embrace and erosion of non-fiction storytelling.

O.J,: Made in America (2016). Credit: ESPN Films.

Intro: The Disappearing Prestige Documentary

Somewhere, hidden in a remote, contractually-obligated corner of the world, sits a nine-hour documentary on the career and untimely passing of famed musician Prince. Few have seen this sprawling examination of the rock star's complicated life and death, yet those granted permission to watch the documentary deem it a "masterpiece"—one of the best non-fiction projects of the 21st century. But this film will likely never see the light of day. So what happened?

The sequence of events goes something like this:

In 2016, filmmaker Ezra Edelman found massive success with his epic eight-hour documentary OJ: Made in America, a thorough investigation of the infamous sports legend and the racial tensions surrounding his landmark trial. The film went on to win the Best Documentary Oscar and is widely considered one of the greatest non-fiction films ever made.

Netflix approached Edelman on the heels of Made in America's success and asked if the filmmaker would consider working on a project about Prince.

Edelman agreed to Netflix's request and spent the next five years curating a comprehensive examination of the enigmatic rock star's life, demons, and legacy.

Amid Edelman's expansive production process, Netflix restructured its non-fiction production arm, laying off notable executives and orienting the division away from prestige fare and toward breezy true crime and celebrity-focused documentaries (typically produced with cooperation from subjects).

Turns out Prince is a more complicated figure than previously thought, as captured by Edelman's documentary. Prince's estate contested the project, concerned with the reputational harm the film would cause, and Netflix, now primarily focused on celebrity puff pieces and serial killers, pulled resourcing from the film (rather than rush to its defense).

As of this writing, the documentary will likely never be released.

What's fascinating about Edelman's Prince project is how its five-year production spans two distinct epochs for non-fiction filmmaking. When Edelman began his work, documentary film was in its prestige era, bolstered by a streaming ecosystem hungry for critically acclaimed projects like Icarus, American Factory, and Boys State. Now, at the project's conclusion, non-fiction storytelling is defined by fluffier, pre-digested content with a built-in audience.

Twenty years ago, documentary film was an extremely niche segment of the entertainment industry, devoid of funding or mainstream interest. Presently, non-fiction filmmaking (in the form of docuseries) stands as a cornerstone of streaming economics, a format bolstered and degraded by an ever-growing demand for cheap, time-consuming content.

So today, we'll examine streaming's embrace and erosion of non-fiction storytelling. We'll explore the mainstreaming of documentary film and the consequences surrounding this welcome yet frustrating development.

Part 1: How Documentaries Went Mainstream

In 1987, documentarian Steve James began following the lives of two African-American high school students in the south side of Chicago as they pursued their dream of becoming professional basketball players. Over the next five years, the filmmaker captured his subjects' excruciating ups and downs as they navigated aging, complicated home lives, and the heartbreaking pursuit of a childhood dream. The result of this experiment was Hoop Dreams, a devastating three-hour epic about race, class, and basketball, widely considered one of the greatest documentaries of all time.

Hoop Dreams (1994). Credit: Kartemquin Films.

By today's standard, Hoop Dreams signifies an outdated mode of documentary storytelling, one where filmmakers worked on meager budgets, had little insight into where their story was headed, and ultimately, prayed their finished product would be acquired at a film festival. Over time, this modest corner of the film industry grew, achieving a handful of breakout successes in a given year, like March of the Penguins, An Inconvenient Truth, and Free Solo.

And then Netflix launched streaming. Suddenly, nascent streaming services were hungry for low-cost documentary content, spawning a near-exponential uptick in financial investment. In 2019, the political documentary Knock Down the House sold to Netflix for $10M; in 2020, Boys State sold to Apple for $12M; and in 2021, Hulu purchased Summer of Soul for an estimated $15M.

Netflix soon made docuseries, documentaries, and reality television a cornerstone of their creative strategy. Over time, these non-fiction projects would come to dominate the streamer's content library as it scaled to 270 million global subscribers.

Documentary production companies, once rag-tag outfits with a handful of passionate employees, started to accept funding from big-name financiers like Airbnb co-founder Joe Gebbia, TV legend Norman Lear, Steve Jobs's widow Lorene Powell, and the Obamas. Somehow, against all odds, non-fiction media became a growth industry.

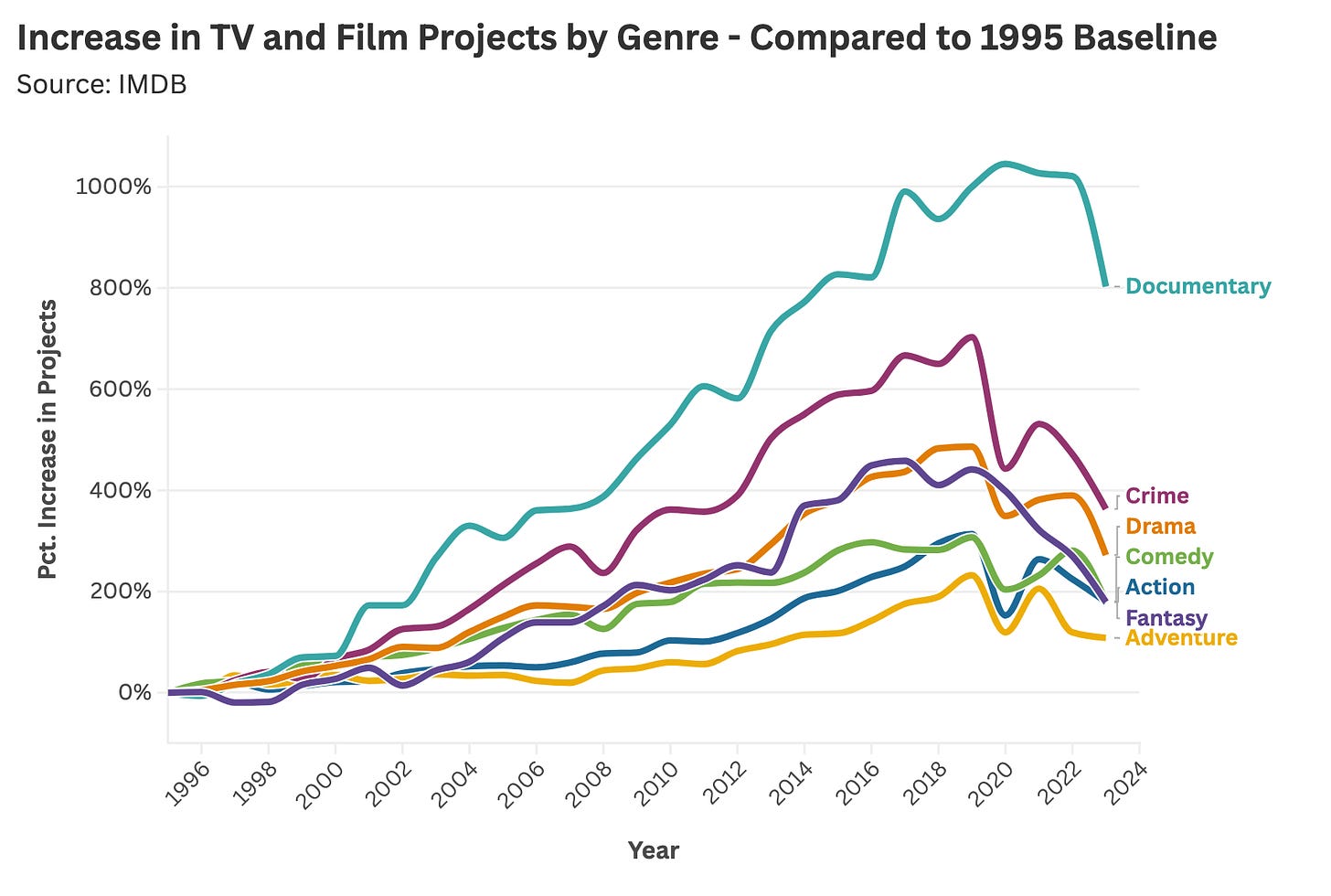

As a result, the number of documentary film and television projects soared, accelerated by a growth-oriented market of ever-proliferating streaming services.

If you're a documentary filmmaker, this is a much-welcomed development, at least financially speaking. You likely chose this profession thinking you would starve for your art, and now your art is in high demand—you have achieved a sustainable career path (congratulations!).

Yet all this funding came with a catch, as renewed investment began changing the artform, transforming two-hour movies (traditionally released in theaters) into four-part docuseries (only released on streaming), with subject matter increasingly oriented around uncomplicated, pre-digested stories with name-brand recognition. In 2022, Netflix reported subscriber declines for the first time in ten years, prompting the streamer (and its competitors) to overhaul its content strategy and scale back costs. Prestige projects (like Edelman's Prince epic) were deprioritized in favor of true crime and sports series.

Non-fiction production companies had expanded and altered their operations in response to streamer demand—as a result, they'd be forced to comply with the ever-changing strategic whims of Hulu and Netflix.

Part 2: The Rise of Disposable Documentary Content

In many ways, documentary film has suffered a fate similar to that of narrative features: distributors now prioritize projects with broad appeal and, ideally, a built-in fanbase—the documentary equivalent of a superhero movie. But instead of superheroes, documentary filmmakers are asked to chronicle the lives of David Beckham, Meghan Markel, Tinder Swindlers, Patrick Mahomes, Jeffrey Dahmer, cults, and Gypsy Rose Blanchard.

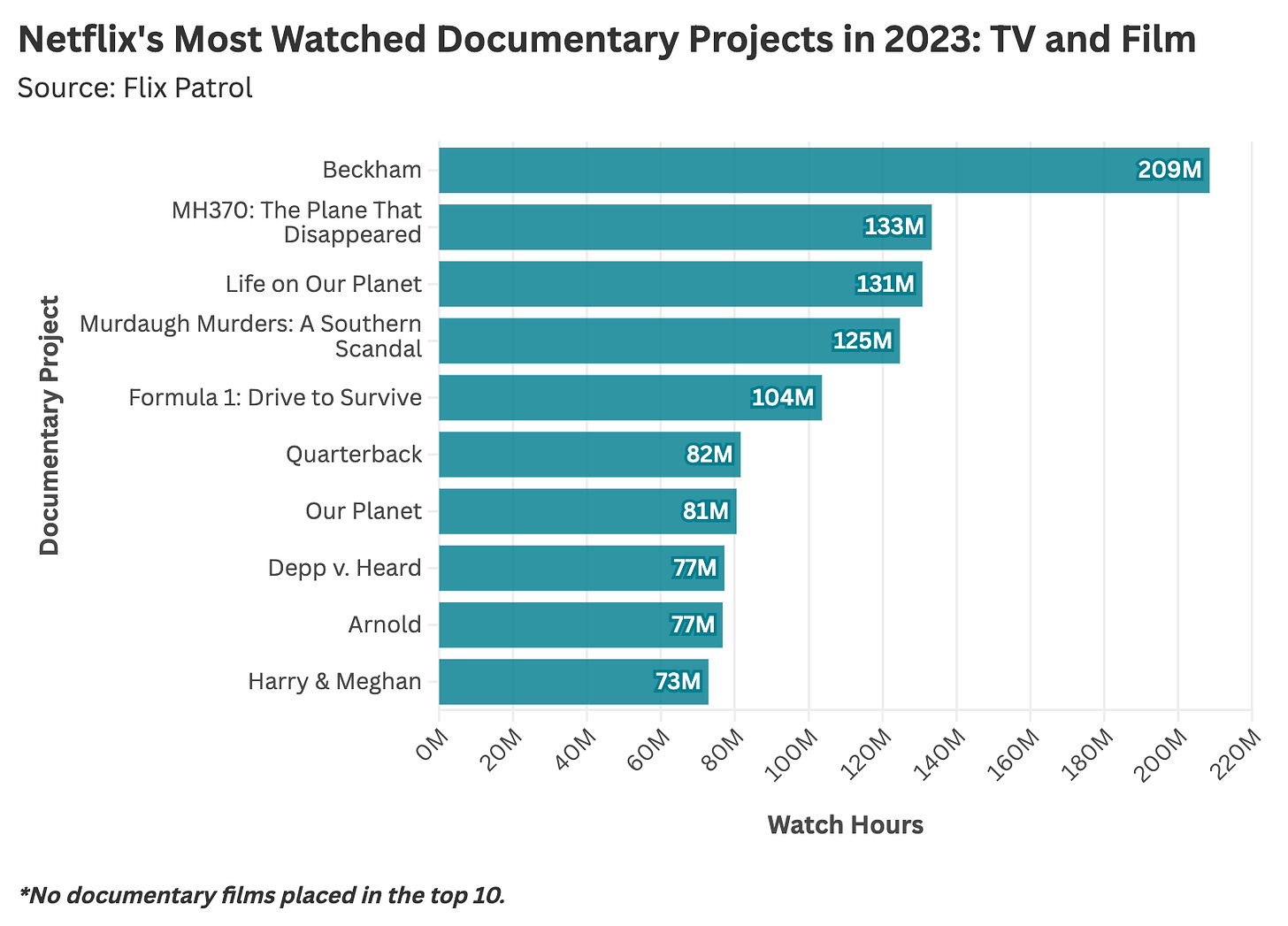

Consider Netflix's most-watched documentary projects of 2023 (film and TV):

These works center around well-known stories and subjects that are easily recognized within a vast sea of digital content.

If I'm being honest, I watched (and enjoyed) several of these docuseries. I like Formula 1 and the NFL, so I happily consumed this content (despite my grandstanding, I, too, am human).

It's not as if Netflix conjured demand out of thin air—they just ruthlessly optimized the artform until it reached its logical conclusion—which is a four- to eight-part docuseries about a celebrity, cult, sports star, serial killer, or all of the above. And you know why they keep making them? Because we watch them (didn't think about it that way, did you?). If everybody wanted to watch Frederick Wiseman's 3-hour and 15-minute documentary (not docuseries) on the New York Public Library, we'd receive an onslaught of library content.

Netflix is our id—they're giving us the true crime content we always wanted but were too afraid to ask for.

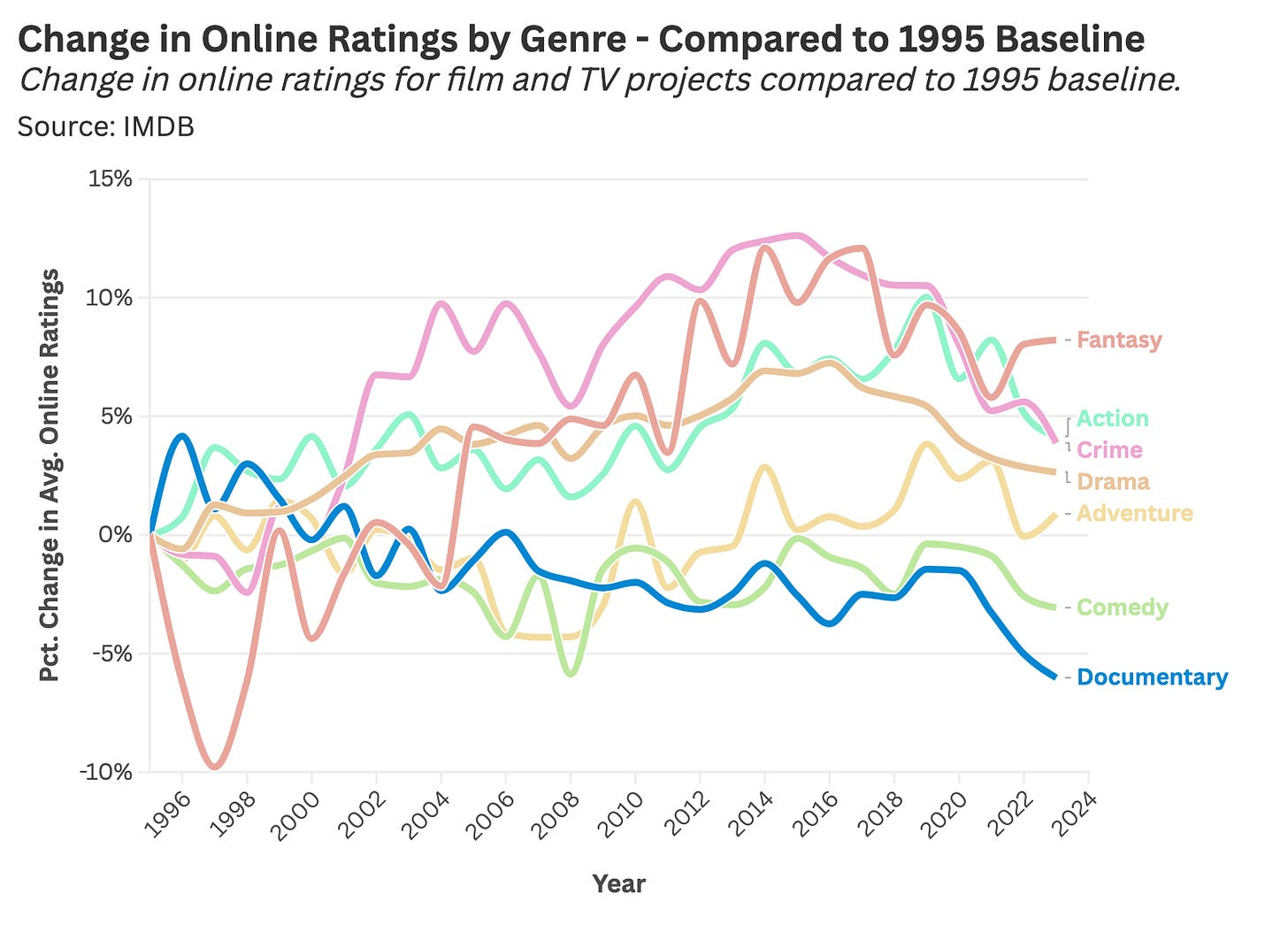

This paradigm shift spawned an immediate decline in documentary quality. Once a bastion of critical praise, non-fiction content has seen a slow-moving dip in online ratings, a trend that rapidly accelerated coming out of the pandemic.

Worse still, the docuseries feeding frenzy of the late 2010s forever altered the economic incentives underlying non-fiction project development, pushing filmmakers away from theatrical releases.

Heading into the pandemic, documentaries were gaining stream at the box office, with breakout hits like RBG, Three Identical Strangers, Won't You Be My Neighbor, and Free Solo all surpassing $15M in 2018.

The pandemic would indelibly change the industry, as Netflix saw massive success with docuseries like Tiger King, Lenox Hill, and The Last Dance, spawning endless imitations from competitors and pushing documentarians toward episodic streaming projects.

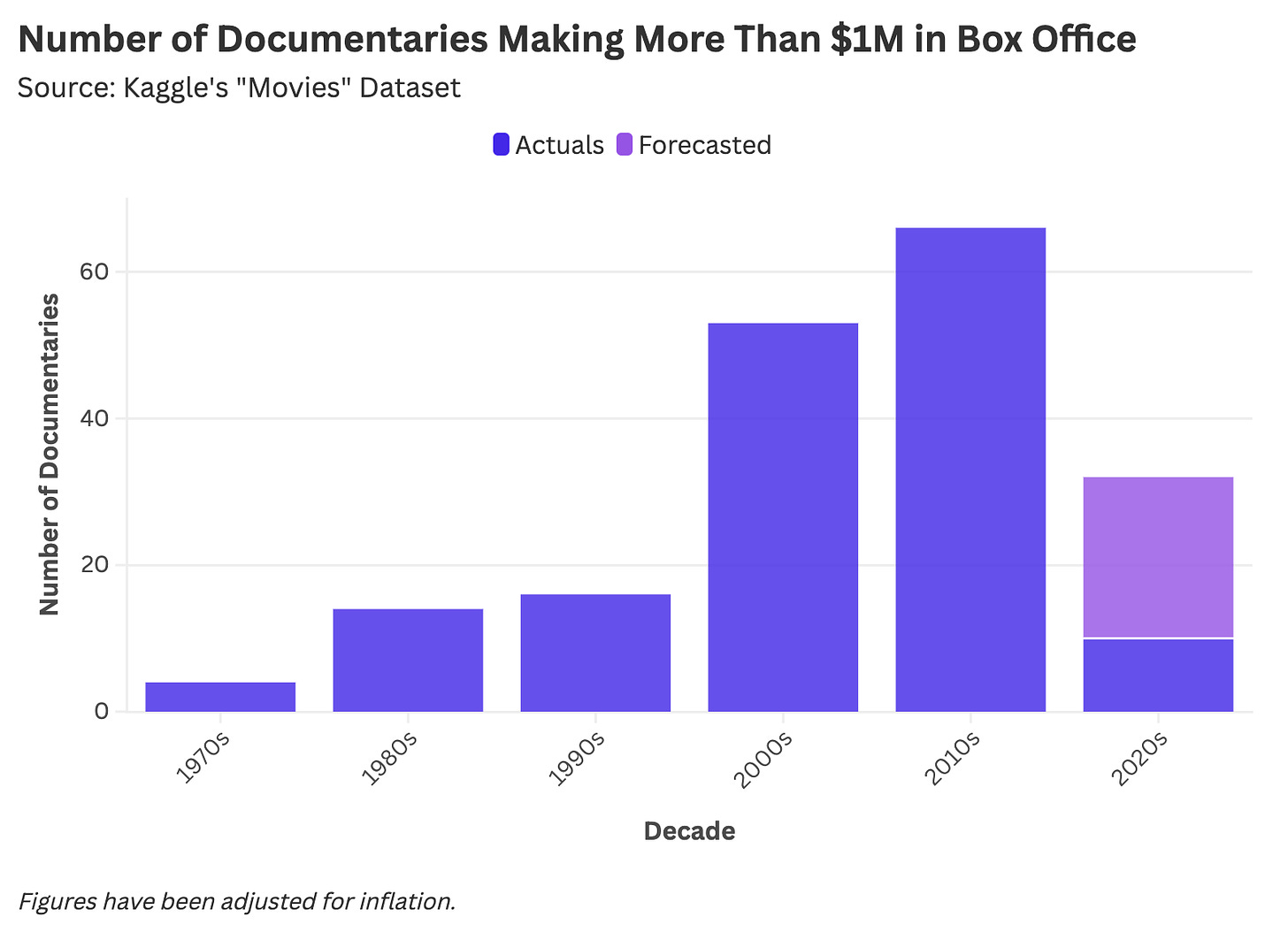

When we examine the number of documentaries with $1M or more in box office over time, we see a rapid uptick in breakout projects at the turn of the century, followed by a precipitous decline in recent years.

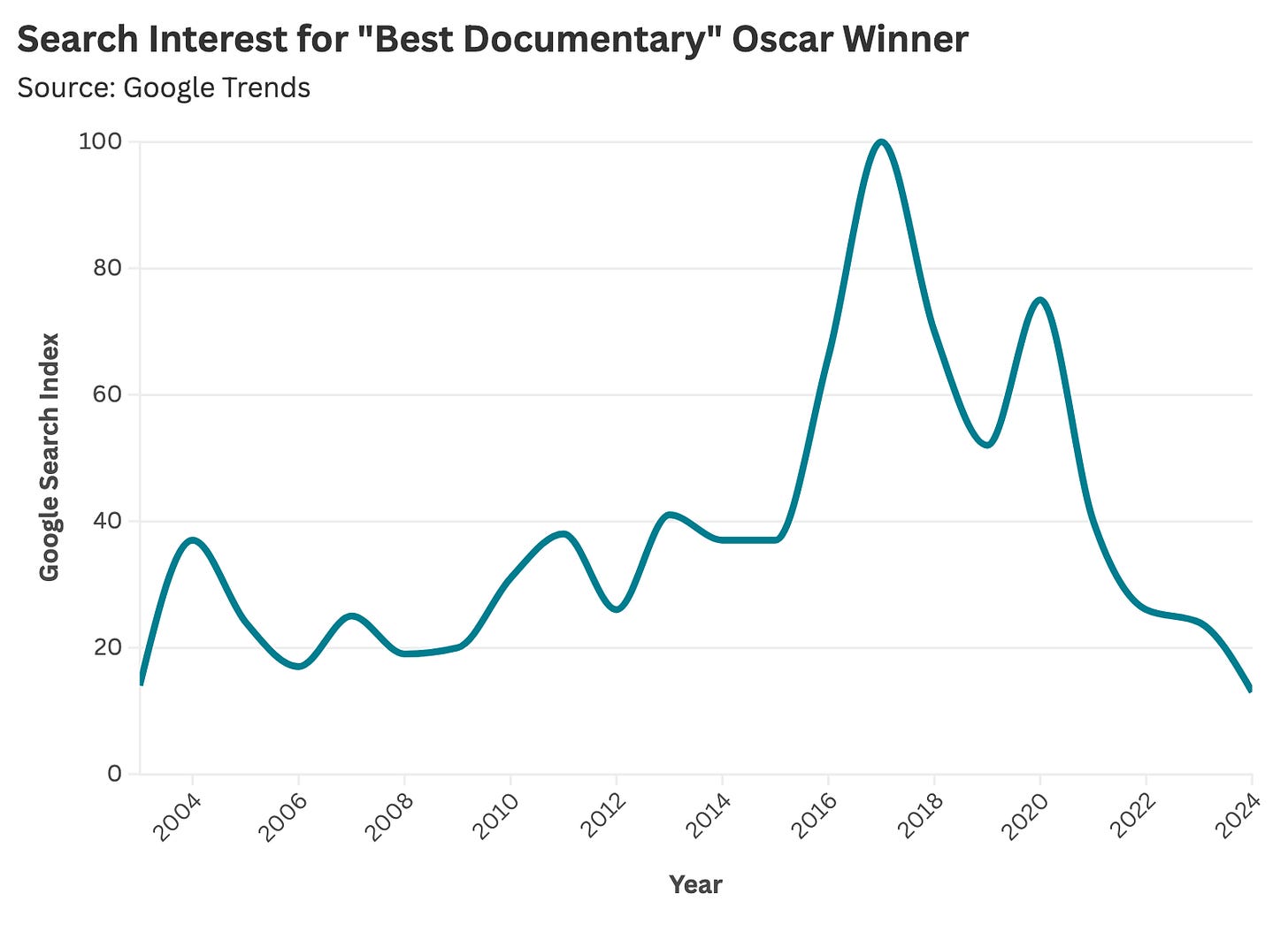

The waning viability of theatrical non-fiction is further reflected in search interest for the Best Documentary Oscar (formerly the most significant PR opportunity available to docs). In the late 2010s, streamer darlings like Icarus and American Factory won Oscars while being widely seen in theaters and at home. Post-pandemic, we've seen fewer prestige projects and declining interest in this story format.

You could make the argument that nobody cares about the Academy Awards anymore—and you'd be right—but the populist appeal of a widely beloved project can also feed into Oscar viewership (making a decline in popular documentaries both an input and output of declining Academy Award interest).

As a result of these industry machinations, documentarians find themselves in a perplexing position. Their chosen career path is 100x more lucrative than it was 25 years ago, but project selection is increasingly limited. This leaves filmmakers with a Faustian bargain:

Make Money: you could "sell out" and produce the 20th Menendez Brothers documentary to great financial reward.

Don't Make Money: You could follow your heart and make a four-hour documentary on the Los Angeles Public Library, unclear if this film will ever see the light of day—an unnerving trend in the documentary space.

Final Thoughts: Am I a Cultural NIMBY?

Tiger King (2020). Credit: Netflix.

I try to maintain a "cool dad" approach to popular culture (if this sounds cringe-worthy, know that was the intention). Sure, there may be entertainment trends that I don't agree with or understand, but I do my best to be "cool" about it 😎. But like any cool dad, my coolness has its limitations.

As I compiled research for this piece, I began grappling with two deeply contrasting beliefs:

All Media is Created Equal: Entertainment is dynamic; no movie genre or television show or storytelling format is sacred. Things change as a function of popular tastes, and we must evolve our appetites in response. Aren't I such a "cool dad" for thinking this (and subsequently telegraphing it to others)? 😎

Netflix Churns Out Garbage: Netflix churns out a bunch of garbage, and I think this stuff absolutely stinks and is ruining our culture. There, I said it. Netflix has ridden the efficient market hypothesis to infinite photocopies of Making a Murderer, Wild Wild Country, Drive to Survive, and Tiger King, and now they're worth $300B. Netflix = bad.

I always assumed that traditional documentary filmmaking, like that of Hoop Dreams and Man on Wire, would exist forever. When Netflix and other streamers embraced non-fiction content, I (wrongfully) thought this would spawn more prestige projects. Now that the artform has changed, I'm confronted with my own hypocrisy—I believe the old-school mode of documentary filmmaking is far superior to this new breed of disposable docuseries.

Apparently, deep down, I'm just a cultural NIMBY. What does this mean? Well, if you live in California for more than a month, you become intimately familiar with the concept of NIMBY-ism, which stands for "not in my backyard." Neighborhood activists, a term that liberally applies to any aggrieved party in California (usually a homeowner), will attend city council meetings to delay new construction, claiming their neighborhood was perfect the way they found it and should, therefore, be frozen in amber. These protestations lead to death by a million papercuts as cities become incapable of evolving, unable to absorb population growth or economic development.

Well, apparently, when it comes to documentary film, I harbor NIMBY-like tendencies—this artform was perfect the way I found it and should never be changed. While I understand that people enjoy celebrity docuseries, I would appreciate it if documentary filmmakers would instead risk financial ruin to produce low-fi, vérité projects optimized for the film festival circuit and/or public television.

And yet, despite rapid changes to the field, renewed financial investment is likely a welcome development for most filmmakers. When I was in college, I interned for documentary filmmaker Kirby Dick, and I did so for free (pretty crazy). Despite having just received a Best Documentary Oscar nomination for The Invisible War, Dick was working out of his house. At the time, I was psyched to have this internship, even though my financial prospects were bleak.

I'm sure if you told that unpaid college intern about the impending documentary boom, he would be ecstatic. Maybe that's the takeaway here: people are getting paid, and no one has to suffer for their art (even if that art is forever changed), and that's all that matters, right?

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Struggling With a Data Problem? Stat Significant Can Help!

Having trouble extracting insights from your data? Need assistance on a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data consulting services and can help with:

Insights: Unlock actionable insights from your data with customized analyses that drive strategic growth and help you make informed decisions.

Dashboard-Building: Transform your data into clear, compelling dashboards that deliver real-time insights.

Data Architecture: Make your existing data usable through extraction, cleaning, transformation, and the creation of data pipelines.

Want to chat? Drop me an email at [email protected], connect with me on LinkedIn, reply to this email, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]