- Stat Significant

- Posts

- How Are Hit Songs Rediscovered Decades Later? A Statistical Analysis

How Are Hit Songs Rediscovered Decades Later? A Statistical Analysis

How does music undergo a cultural revival long after its original release?

Stranger Things (2022). Credit: Netflix.

Intro: Is "Bohemian Rhapsody" the Most Rediscovered Song of All Time?

"Bohemian Rhapsody" began its remarkable journey in 1975 when Queen first released their rock-opera masterpiece as the lead single on their fourth studio album, "A Night at the Opera." Naturally, record executives hated the song, believing its mix of incongruous music styles and 6-minute run time to be commercial kryptonite. Well, they were wrong, and the song quickly surged to number nine on the Billboard Charts.

Fifteen years later, "Bohemian Rhapsody" reentered the zeitgeist following the death of Freddie Mercury, Queen's enigmatic lead singer, who passed away due to complications from AIDS. Mourning fans adopted "Bohemian Rhapsody" as their de facto theme song, and a re-released recording catapulted the single to number one on the UK charts.

Less than a month after the song's re-release, the movie Wayne's World employed Queen's masterwork in a comedic setpiece during a spirited round of carpool karaoke. The convergence of these unrelated pop culture moments propelled "Bohemian Rhapsody" to widespread ubiquity, and the song surpassed the success of its initial release.

Twenty-six years later, "Bohemian Rhapsody" experienced a fourth surge in popularity following the release of a Queen biopic, which was (of course) titled Bohemian Rhapsody. The film grossed $910M worldwide, and the titular tune returned to the Billboard Charts, peaking at 33.

Indeed, a single piece of music can live many lives. Bohemian Rhapsody's continuous rediscoveries are rare, though not entirely unprecedented. Since the advent of the Billboard Hot 100 in 1958, over 75 songs have graced the charts multiple times across distinct eras. So what spawns these random acts of cultural revival? How does a song achieve a second (or third) commercial life? And how are songs rediscovered in the age of social media and music streaming?

Outsmart the Learning Curve is your go-to resource for data-driven self-development ideas for everyday people. Subscribe to receive free weekly newsletters packed with:

✅ Fresh self-improvement ideas backed by accessible scientific research

✅ Actionable strategies for personal and professional growth

✅ Thought-provoking insights that challenge conventional wisdom

How Has Music Rediscovery Changed Over Time?

We'll define a hit song as "rediscovered" if that piece reenters the Billboard Charts five or more years after its first appearance in the Top 100. Obviously, a song that never reached the Top 100 can be rediscovered, so our definition provides a microcosmic view into music repopularization.

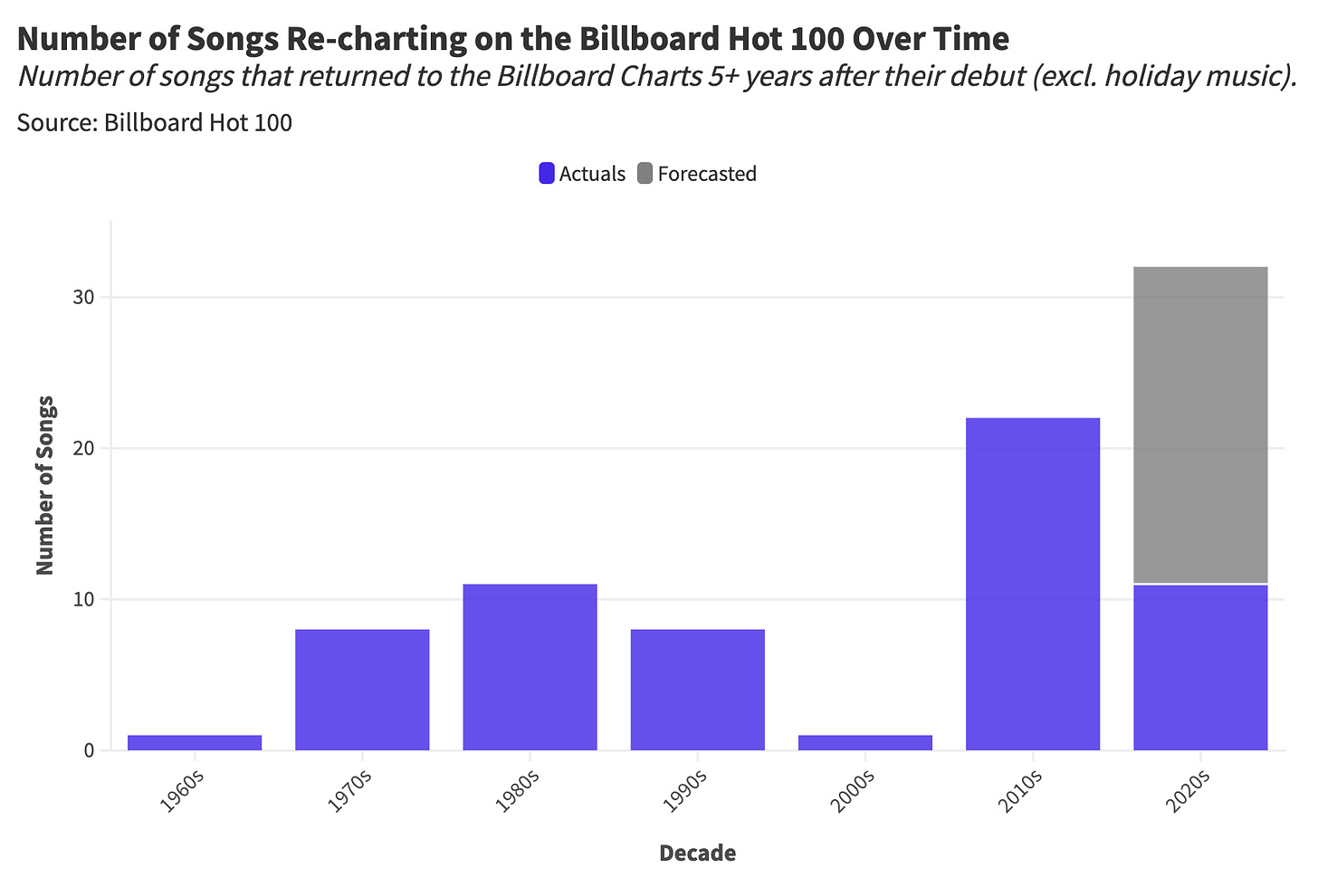

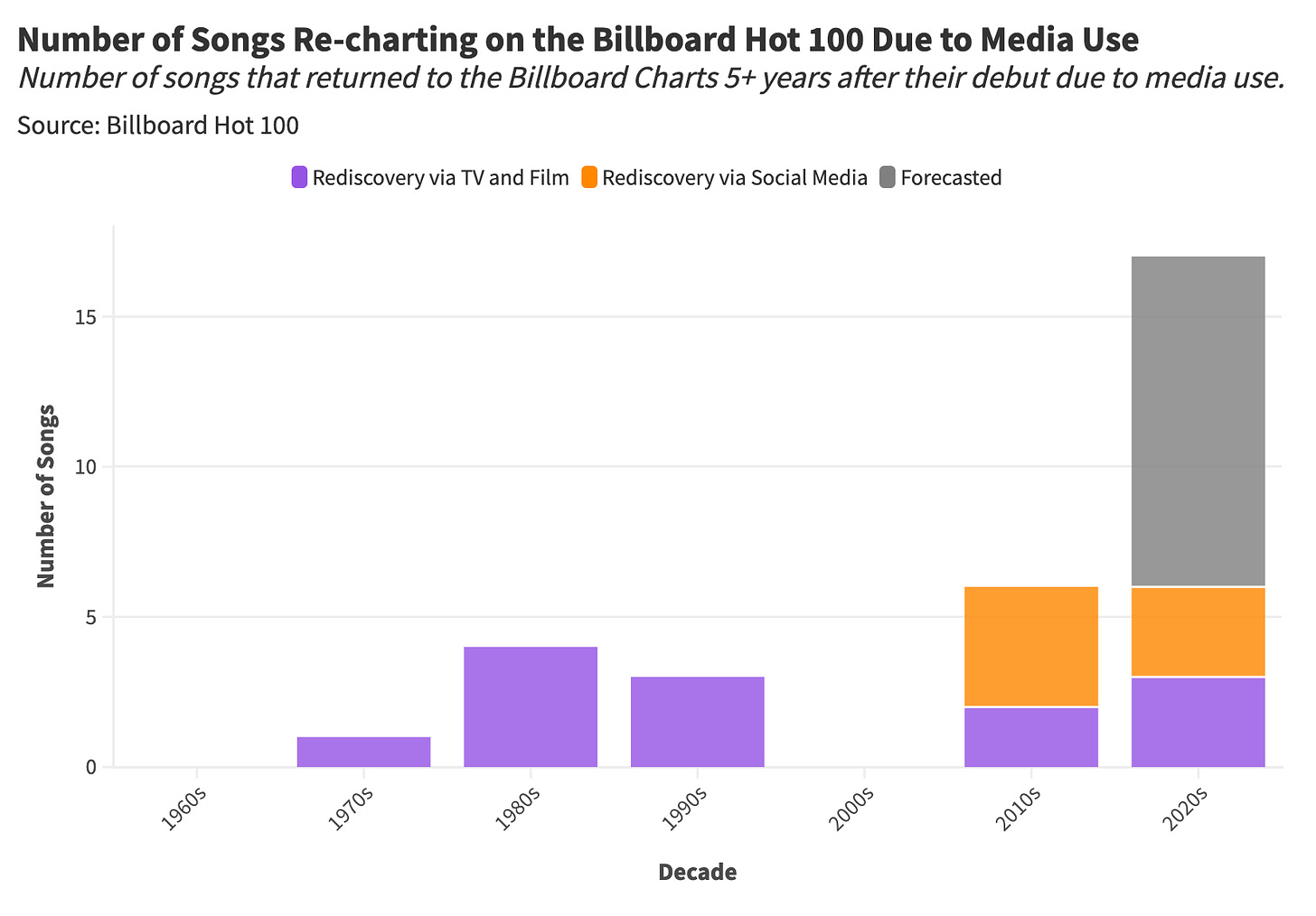

Now that we've defined "rediscovery," we can delve into the frequency of song revivals throughout Billboard's seventy-year history. Is music repopularization a modern internet phenomenon or an occurrence that predates streaming services and TikTok? The answer is both. In graphing the frequency of re-charting songs by decade, we find two distinct eras of music rediscovery:

Our first "era" of music rediscovery spans from the 1970s to the 1990s, reaching a notable peak in the 1980s. This period is followed by a lull in song repopularization during the 2000s before a dramatic uptick in re-charting works throughout the 2010s and early 2020s.

Our chronology of song revivals raises more questions than answers. What fueled an uptick in re-charting songs between 1970 and 1990? And, assuming the internet is somehow responsible for the post-2010 swell in rediscovered works, what digital phenomena contributed to this spike?

Song Rediscovery Reason #1: Songs Re-charting Through Re-release

Believe it or not, "The Star-Spangled Banner" has had multiple stints on the Billboard Charts. I don't know about you, but I've never listened to a nationalistic anthem (American or otherwise) and thought, "This song needs to go on my deep work playlist." So how did a ceremonial song traditionally sung at the beginning of American sports games hit the Billboard Charts twice? Well, Whitney Houston is why.

On January 27th, 1991, ten days into the Gulf War, Whitney Houston performed "The Star Spangled Banner" at Super Bowl XXV to a television audience of nearly 80 million viewers. The public's enthusiastic response to Houston's performance led to its release as a standalone single (on physical media!).

Ten years later, Houston's stirring cover of the American anthem was re-popularized in the months following the September 11th attacks, which prompted record executives to re-release the song as a commercial CD single.

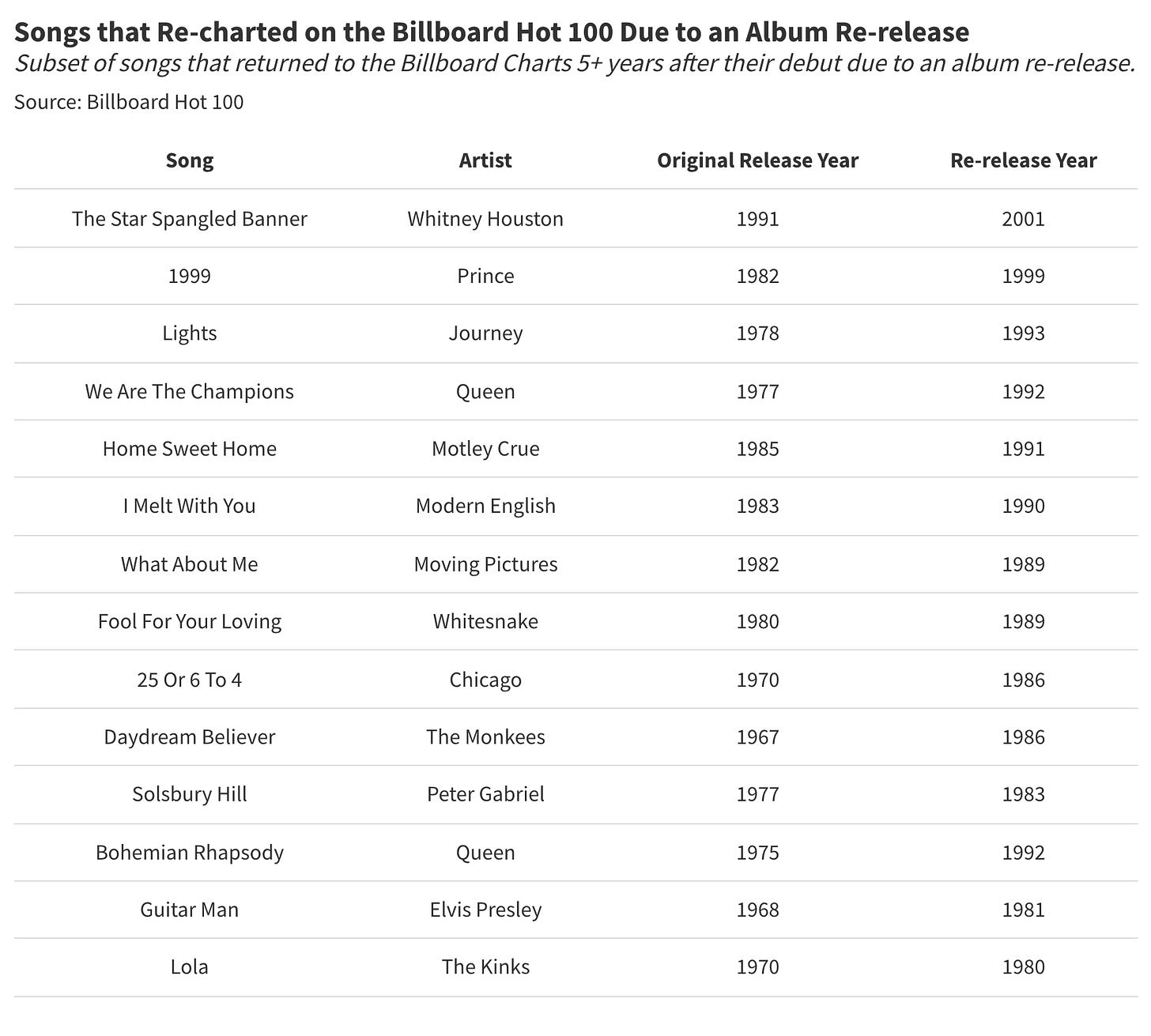

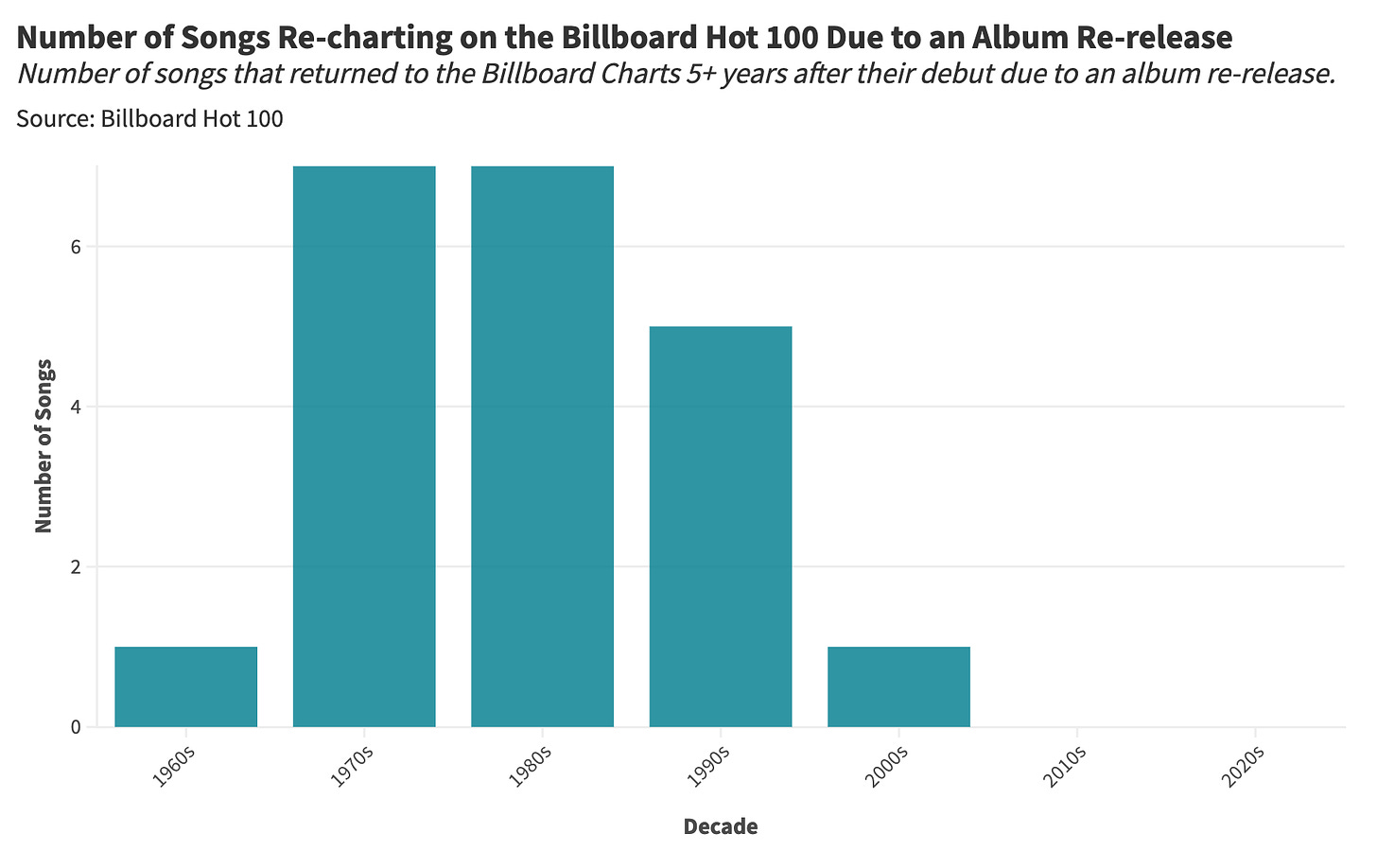

Re-releasing songs, whether it be as individual singles or as part of a compilation of hits, was exceedingly popular during the 1970s and 1980s:

In fact, most songs that reentered the Billboard Charts between 1970 and 1990 were re-releases:

That said, music re-releases are a pre-streaming phenomenon, a relic from the age of physical media. Suppose you're a record executive in 1993 and want to cash in on a song or artist in your portfolio reentering the zeitgeist—what do you do? You re-release their work and compel consumers to repurchase the same content in a slightly different package or form factor.

Today, re-releases are an anachronism; artists do not benefit from the same song having multiple listings on Spotify (barring some sort of stylistic variation between renditions). So, if you're feeling particularly patriotic, so much so that you want to listen to Whitney Houston's performance of "The Star Spangled Banner," you no longer have to fork over $12 for a vinyl or CD—you can stream it on Apple Music or watch it on Youtube.

Song Rediscovery Reason #2: Film, Television, and Social Media

1986 was a productive year for The Beatles, despite the band's breakup 15 years prior. The band's cover of "Twist and Shout" was prominently featured in memorable scenes from Ferris Bueller's Day Off, with Ferris overtaking a parade demonstration to lip-sync the tune, and Rodney Dangerfield's Back to School (released two days after Ferris Bueller), with Dangerfield covering The Beatles classic. Twenty-four years after its release, "Twist and Shout" reappeared on the Billboard Charts, where it peaked at number 23.

Since 1958, a handful of songs have returned to the Billboard Charts due to their inclusion in TV shows and movies:

Although our sample is limited, we find several instances of hits from the 1960s and early 1970s being utilized in films released during the 1980s and early 1990s, such as "Stand by Me" in Stand by Me, "Unchained Melody" in Ghost, "Do You Love Me" in Dirty Dancing, and, of course, "Bohemian Rhapsody" in Wayne's World. Perhaps there is a predictable time interval when hit songs ripen in nostalgic value, or maybe this cluster is a smattering of randomness.

We also see a relative decline in media-driven rediscovery after 2000, likely due to increasing fragmentation in media consumption. Few contemporary movies or TV shows can match the cultural impact of Dirty Dancing or Ferris Bueller's Day Off (with the exception of the Marvel Cinematic Universe or Stranger Things). But film and television are only half of the story.

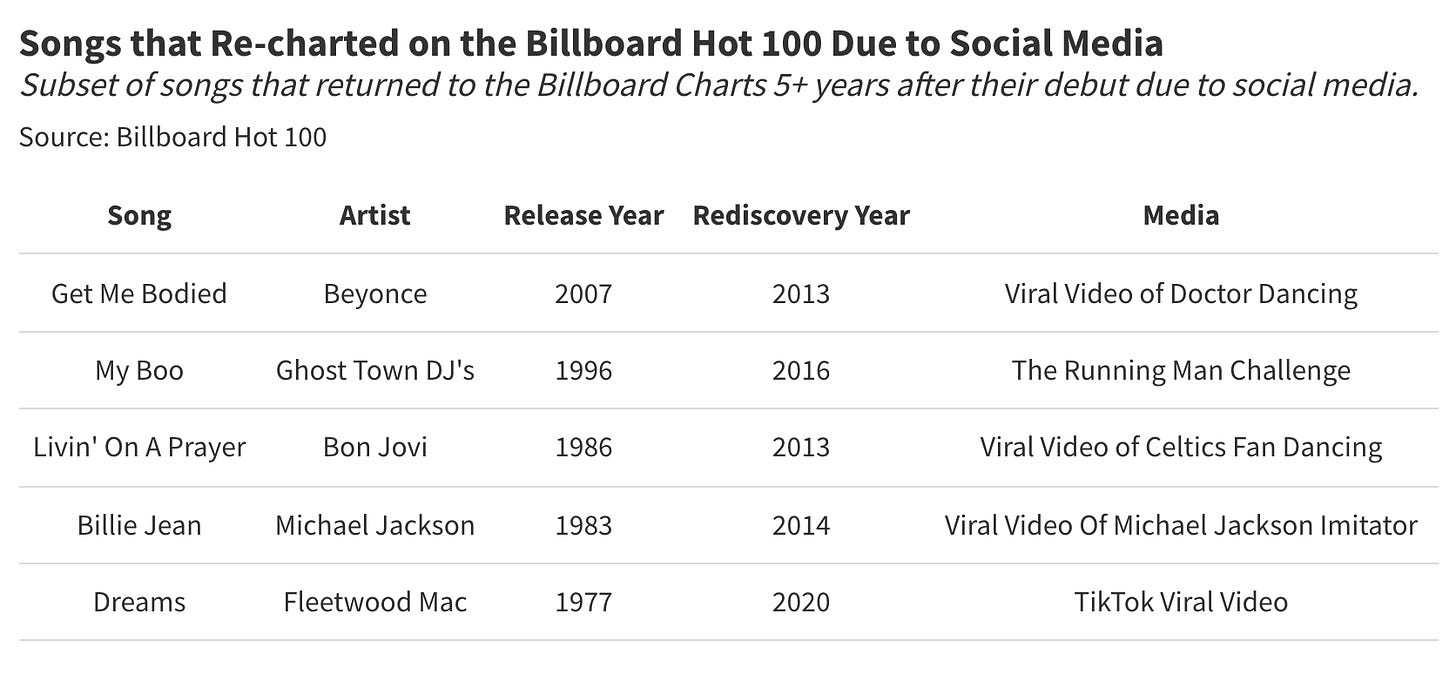

Social media, on the other hand, is perfectly calibrated to revive once-beloved hits, with platforms like Facebook and Instagram resurrecting songs through viral videos and dance challenges.

When we chart media-driven song revivals over time, we observe a slight uptick in rediscovery during the 80s, followed by a significant increase in music revivals after 2010, primarily fueled by social media.

Services like TikTok and Twitter enjoy massive reach, formalize cultural trends by surfacing virality to their users, and meme-ify recognizable songs to convey complicated emotions within the contents of a short-form clip. For better or worse, these platforms are the future of music repopularization.

Need Data Help? Stat Significant Has You Covered!

Enjoying the article thus far and want to chat about data and statistics? Need help with a data or research project? Well, you’re in luck because Stat Significant offers data science consulting services!

If you're looking to turn your data into strategic growth, drop me an email at [email protected], connect with me on LinkedIn, or book a free data consultation at the link below.

Song Rediscovery Reason #3: Songs Re-charting After a Musician's Death

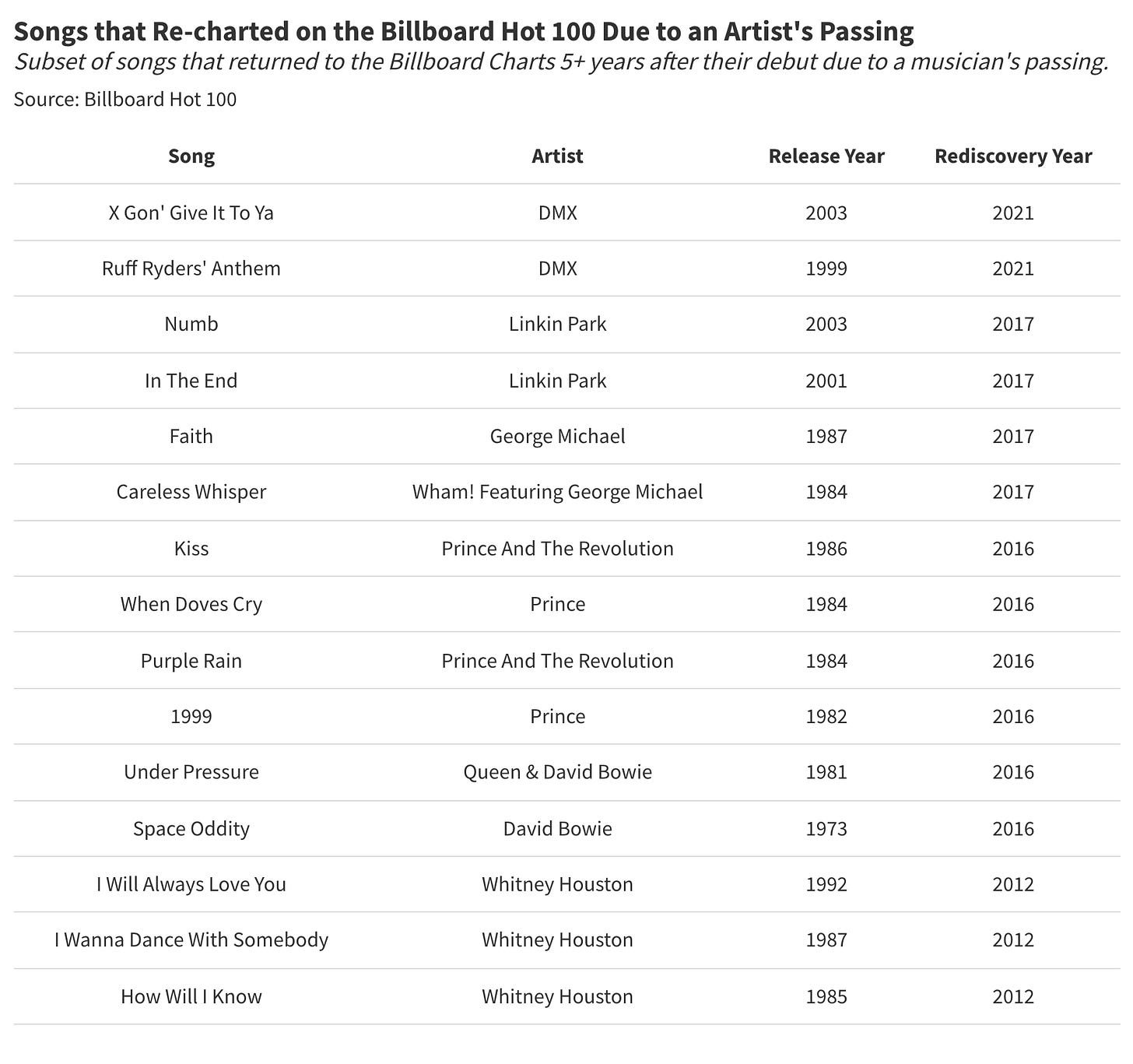

On April 21st, 2016, beloved rock icon Prince passed away at the age of 57. Prince was a fixture of American pop culture for over 20 years with 47 hit songs, a campy film classic in Purple Rain, a highly public and bizarre name change, and an iconoclastic public persona (which was memorably spoofed in a Chapelle Show skit).

Prince's music catalog experienced a noteworthy uptick in streaming activity following his passing, with global listenership doubling in the months following his death. In 2016 alone, Prince's music portfolio saw 66 million on-demand audio streams, 7.7M in album sales (the highest of any artist in 2016), and seven songs reentering Billboard's Hot 100.

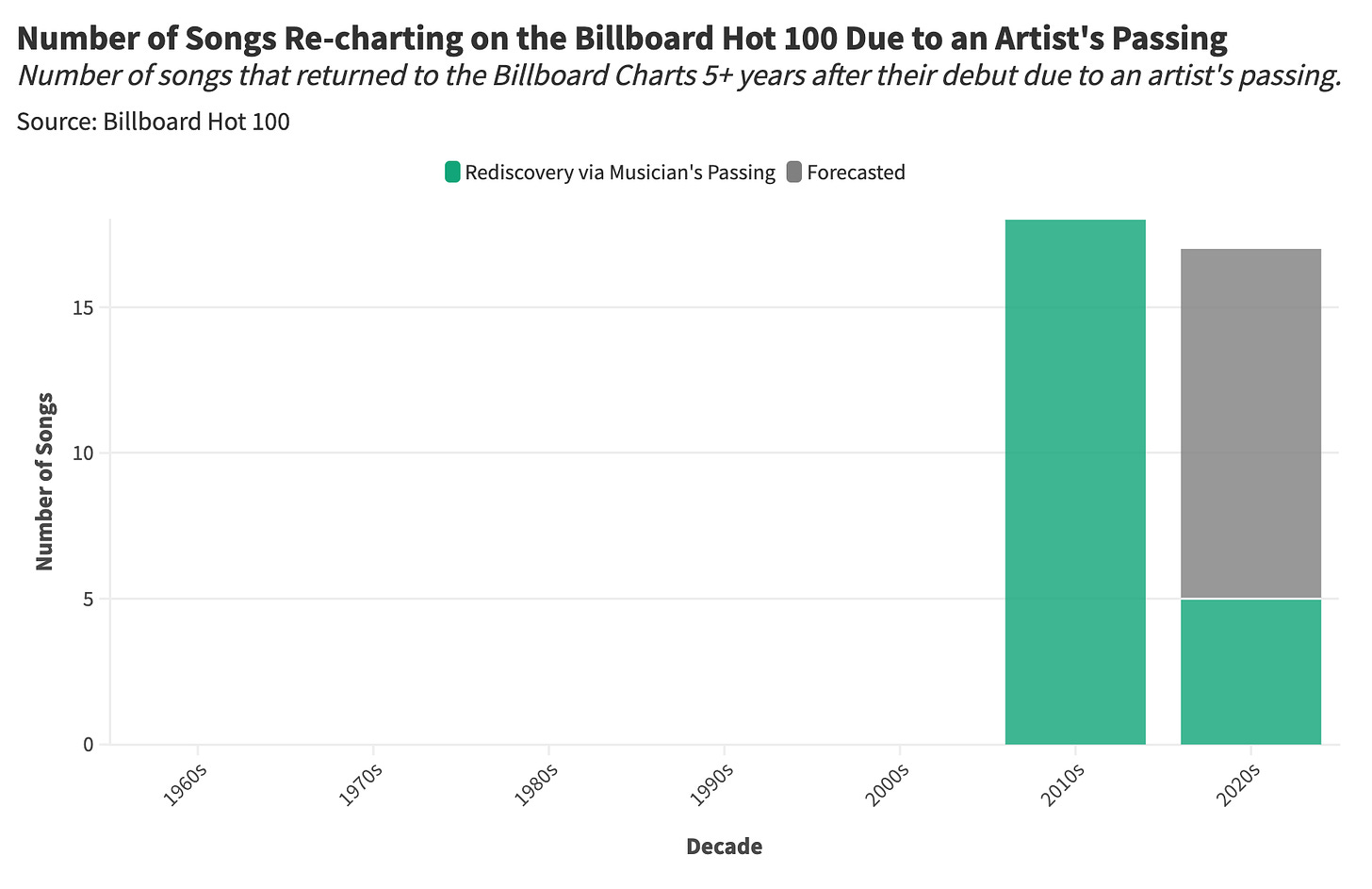

Prince's posthumous revival is one of many high-profile deaths that have brought artists back onto the Billboard Charts:

And yet, rediscovery in the aftermath of a musician's passing is a relatively new phenomenon:

How is this possible? Why did Prince and Whitney Houston see their songs reach the Billboard Charts following their death, but John Lennon and Janis Joplin did not?

Let's consider the case of John Lennon, a much-beloved artist with a lengthy hit catalog whose work did not re-chart after his passing in 1980. Assassinated by a crazed gunman, Lennon's death received ample media coverage. So why did this widely-covered tragedy not encourage a mass rediscovery of Lennon's work? The answer to this question is heavily influenced by how you define "rediscovery."

Before streaming, consumers owned their favorite music via CDs, records, cassettes, and digital downloads from iTunes. When John Lennon passed away in 1980, grieving fans likely consoled themselves by playing a previously purchased vinyl or cassette tape. And if Lennon passed away today? His fans would go to Spotify and stream his classics, sending his music up the Billboard Charts. In both scenarios, Lennon's discography sees an uptick in listenership, but only in the case of music streaming does this engagement constitute an increase in commercial activity.

Song Rediscovery Reason #4: Holiday Music

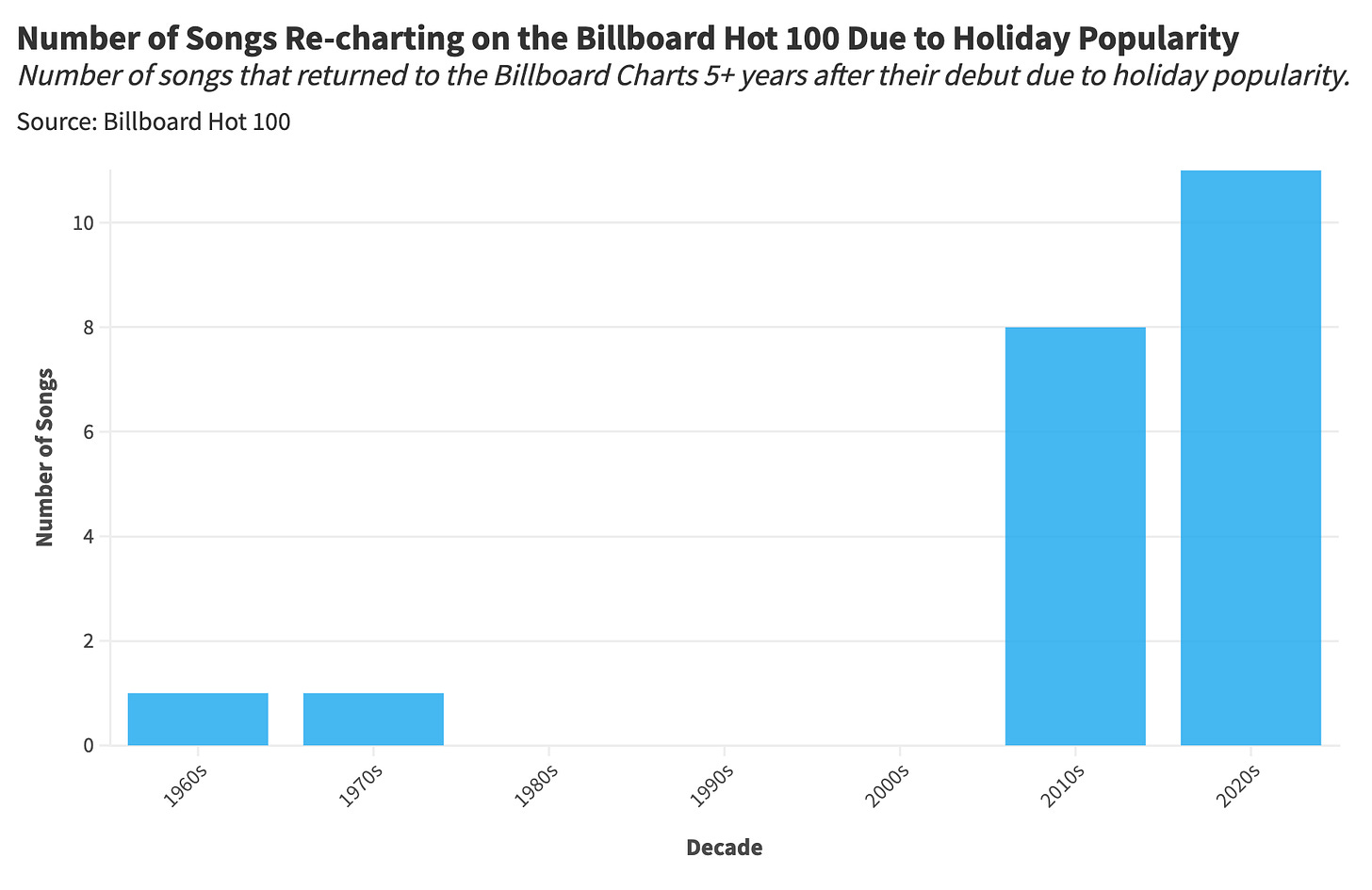

An evergreen Christmas hit may be the pinnacle of commercial success in the music industry. Mariah Carey, for example, reportedly collects over $2.5 million between mid-November and the end of December every year, thanks to the enduring popularity of "All I Want for Christmas Is You." Holiday hits are "rediscovered" on a shorter timeline, fading from collective memory at the end of a holiday season, only to reemerge within the zeitgeist after eleven months of cultural dormancy.

According to Billboard data, the frequency of re-charting holiday music has significantly increased in recent years.

That said, the term "rediscovery" may be misleading here, as many of these songs never exited the public consciousness (for more than twelve months at a time). So why are we seeing a recent uptick in re-charting holiday songs?

Throughout its history, Billboard has continually revised its rankings methodology, shifting from radio play data to physical sales, then to digital downloads, and, finally, to audio streaming. In 2012, Billboard added streaming data to its ranking methodology in response to Spotify's rapid ascendence. Consequently, 2012 was the first year we see Christmas music reemerge on the Billboard Hot 100.

The usage-based economics of streaming services are especially favorable for songs with evergreen seasonal demand (relative to works unaffiliated with a holiday). Before Spotify and Amazon Music, consumers typically made a one-time purchase of a few Christmas classics or relied on radioplay of holiday hits. Streaming has enabled Mariah Carey, Michael Bublé, and Wham! to consistently capitalize on the enduring popularity of their holiday classics.

Final Thoughts: The Future of Nostalgia

Wayne’s World (1992). Credit: Paramount Pictures.

In 1688, scientists began studying an unknown mental state experienced by Swiss Mercenaries in far-off European lands. In his study of the mercenaries, Swiss physician Johannes Hofer coined the term "nostalgia" from the Greek nostos (homecoming) and algos (pain). Hofer described nostalgia as a psychopathological disorder characterized by sufferers manic with longing.

During the second half of the twentieth century, nostalgia slowly transitioned from medical diagnosis to everyday emotion, a feeling of bittersweet longing rather than a concerning pathology. In 1979, sociologist Fred Davis showed that the term "nostalgia" was heavily associated with words like "warm," "old times," and "childhood" rather than terms like "homesickness." Today, nostalgia's most culturally relevant definition concerns "a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past."

Music rediscovery, in most of its forms, is largely driven by the pleasurable pull of nostalgia. Whether sparked by a memorable movie scene, the poignant loss of a beloved artist, or the comforting warmth of Christmas cheer, the collective urge to rediscover a song stems from the deep-seated ties between a piece of music and cultural memory.

Looking ahead, the music industry is poised to see even more song rediscovery. For just $10 a month, Spotify and Apple Music provide access to (nearly) all recorded music in human history. When an artist dies, their entire discography is just three clicks away.

"Bohemian Rhapsody," with its repeat waves of cultural rediscovery, currently stands as a unique outlier—a song resurrected across multiple eras. But what if Queen's eccentric masterpiece is merely the first song to experience numerous commercial revivals? There may be other "Bohemian Rhapsodies" to emerge. Indeed, the future is bright for works of the past.

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]