- Stat Significant

- Posts

- Do Animals Make Movies Better? A Statistical Analysis

Do Animals Make Movies Better? A Statistical Analysis

Answering the hard-hitting questions surrounding animal depictions on the big screen.

101 Dalmations (1961). Credit: Walt Disney Studios.

Intro: Dalmation-mania

The success of Disney's 101 Dalmations is the best and worst thing that has ever happened to dalmations. The 1961 animated film and its 1996 live-action adaptation led to a dramatic spike in dalmatian popularity, as the breed's distinctive appearance and charm (as portrayed in the films) made them highly desirable. Unfortunately, dalmatian hysteria ultimately led to overbreeding and, subsequently, numerous efforts to rescue and rehome unwanted dogs (author's note: I acknowledge this anecdote is a bit depressing).

Believe it or not, the Disney-spawned dalmatian craze is just one of many breeding trends stemming from popular culture. Over the last eighty years, numerous celebrity canines have influenced the popularity of their respective breeds.

Source: The New York Times.

Is it crazy for annual dalmatian adoptions to rise 300% due to a 79-minute movie? Absolutely. Is this statistic less perplexing when considering the often-intense innate connection between audience and on-screen animal? Also, yes.

Some of the greatest moments in cinematic history stem from unforgettable on-screen creatures:

The carnivorous shark in Jaws

The virtue of Toto in The Wizard of Oz

The hilarity of Mike Tyson's tiger in The Hangover

The profanity-laden tirades of Samuel L. Jackson while fighting Snakes on a Plane

Since the days of Lassie, Bambi, and Dumbo, the portrayal of animals on film has served as a powerful element of storytelling and a significant draw for audiences. So today, we'll explore on-screen animal trends over time, whether these depictions improve the reception of their films, and the cinematic tropes associated with certain species.

Do Animals Make Movies Better?

Hollywood relies on typecasting when selecting performers, human or otherwise. Take Robert De Niro (a human actor), who often portrays intimidating characters marked by profound inner turmoil, like Taxi Driver's Travis Bickle or Raging Bull's Jack LaMotta. Audiences familiar with De Niro's history of tough, gritty, and morally complex roles have a deeper connection to subsequent performances, enhancing the impact of his characters.

Much like Robert De Niro (and most other human actors), animals are also typecast on the big screen. Consider the lion, a symbol of courage and majesty. Since 1924, MGM has relied upon a roaring lion to introduce their films, illustrating the grandeur and strength of the MGM brand.

Credit: MGM Studios.

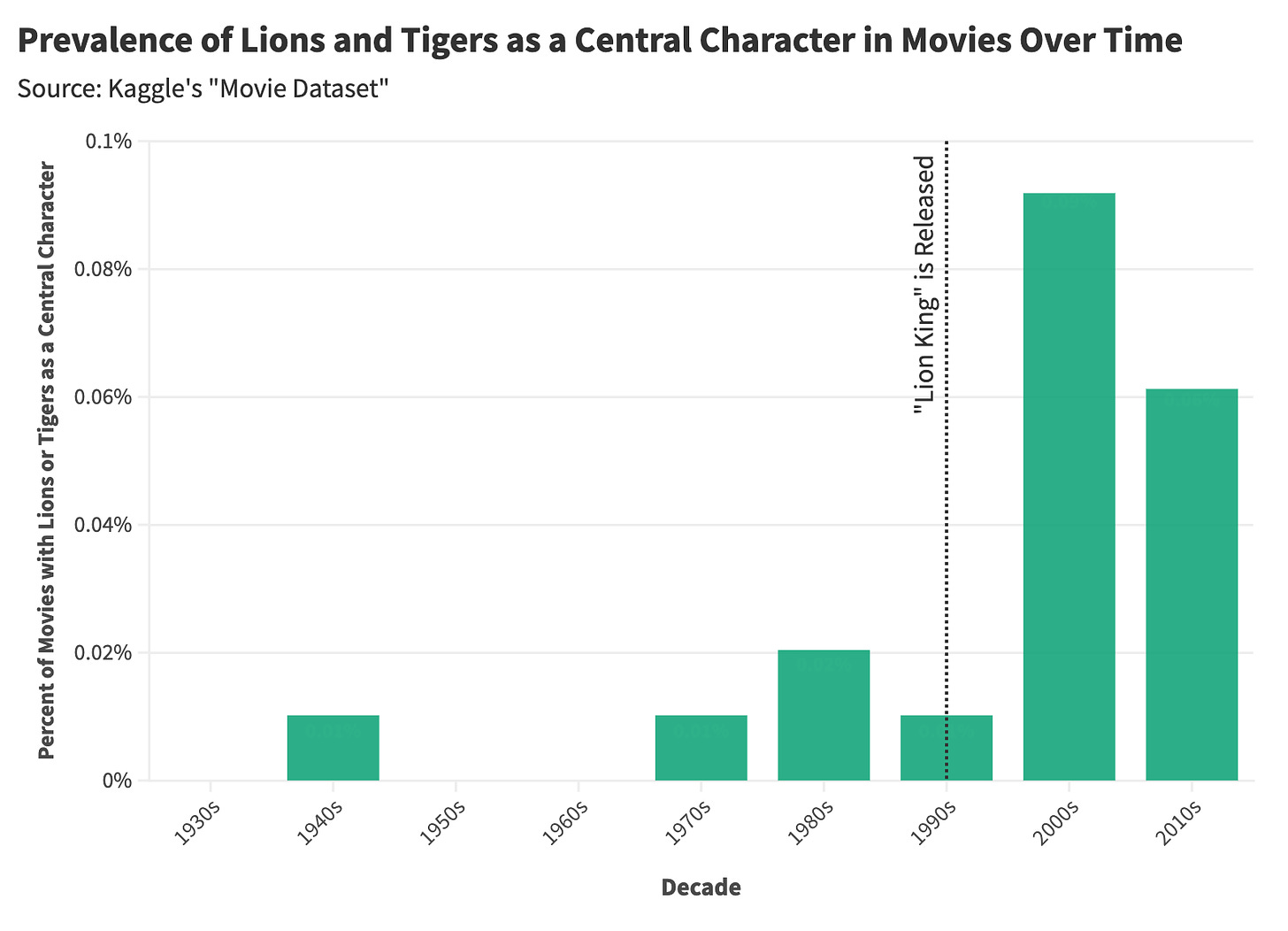

Apart from MGM's figurehead, the first sixty years of movie history featured few depictions of lions on-screen, likely due to the practical constraints of working with fierce, predatory cats. The Wizard of Oz (and The Wiz) are notable exceptions, where the lion performances are heavily anthropomorphized, with the cowardly traits of these characters purposefully subverting cultural expectations.

The Wizard of Oz (1939). Credit: Warner Brothers Studios.

The 1990s ushered in a new era of lion cinema (which is a subgenre I just coined). Advances in animation allowed for the depiction of wild creatures rarely seen on-screen, and The Lion King debuted to tremendous commercial and critical success. Following The Lion King, jungle cats became a staple of adventure movies, and the number of films featuring prominent lion characters increased.

Most films cast lions and tigers as prideful bastions of moral certitude—and we readily accept these depictions because that's how we think lions operate. There is often cultural and mythological significance attached to a given animal that lends that creature to specific genres and storytelling tropes. Using a dog or cat on-screen capitalizes on our existing emotional relationship with these creatures. So, are these animal depictions effective? Do on-screen creatures sway audience reception?

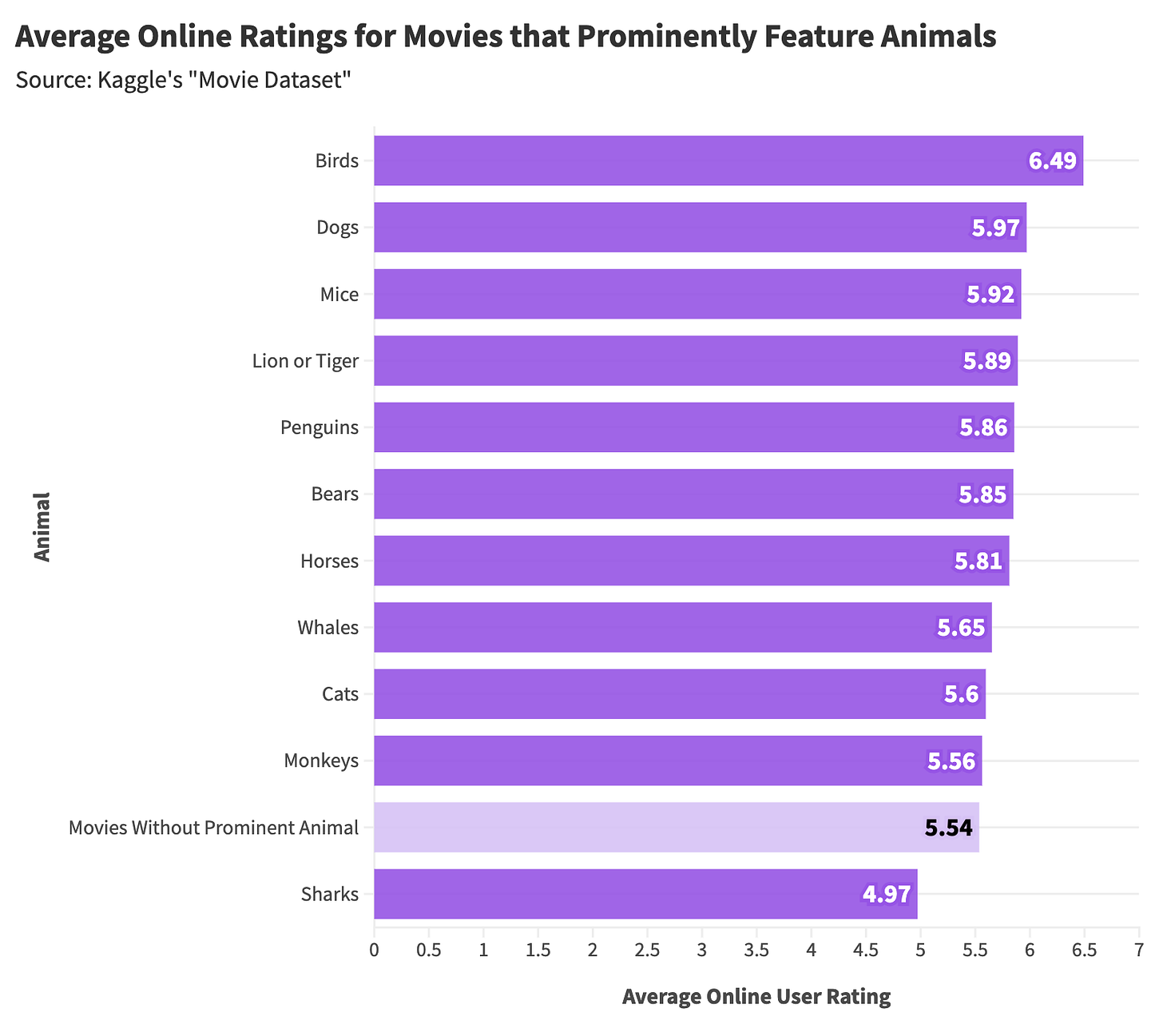

In short, the answer is yes; movies featuring animals as a central figure receive higher online ratings than the average film, with the exception of shark movies.

Why are shark movies bad? Well, that's because shark cinema is comprised of 1) Jaws and 2) a long history of low-effort Jaws rip-offs. Still, maritime monster movies perform well at the box office, which is why The Meg franchise may continue indefinitely.

With advances in wildlife training, CGI, and animation technology, Hollywood has incorporated more animal depictions into films over the last three decades.

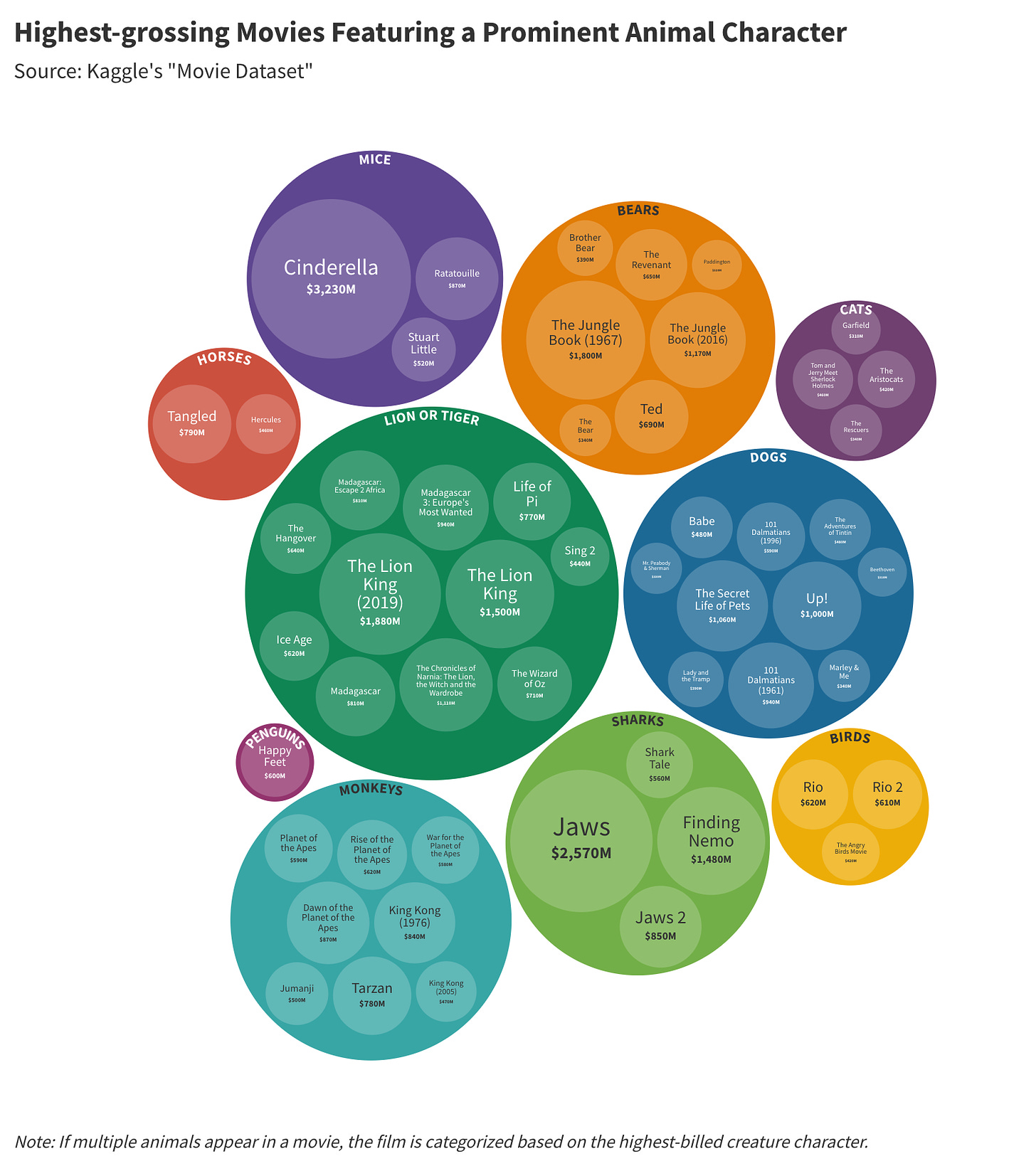

Family audiences are particularly receptive to fantastical movies with anthropomorphized creatures, which captivate children's imaginations while delving into complex themes. The highest-grossing films with prominent animal characters mainly cater to younger audiences (with a strong showing from lions and tigers).

Indeed, well-rendered on-screen animals can forge a significant cultural footprint. It's hard to understate the sheer ubiquity of Paddington dolls on display throughout London. Seth Macfarlane's Ted garnered a sequel and a television series (soon to be released on Peacock). Terry the Terrier, who played Toto in The Wizard of Oz, has her own Wikipedia page, and Bart the Bear enjoys a filmography that outshines most working actors.

Yet the growing frequency of on-screen animal appearances has led to the crystallization of certain storytelling conventions. Audiences now have an expectation for how dogs and cats should be portrayed in films, as years of imitation have given way to well-worn tropes. So, if animals like dogs, cats, and bears make movies better, what types of films typically feature these creatures? What makes a shark movie? What are the hallmarks of horse cinema? Why do we love on-screen dogs so much?

There are too many AI newsletters out there, a fact that could warrant its own statistical analysis, but Yaro on AI and Tech Trends is a publication I find legitimately helpful.

It's an efficient 4-minute newsletter that helps readers stay savvy on AI and other tech trends. Yaro's bite-sized briefings provide the latest learnings on AI development and AI tools with unique insight you won't find elsewhere.

The Genre Tropes of Creature Content

Before Jaws, the monster movie featured supernatural creations like Frankenstein and Nosferatu. Jaws redefined the genre, introducing nature as a threat equal to that of the supernatural. Audiences were terrified by the prospect of a gigantic man-eating shark, with some beach communities claiming a drop in tourism resulting from Spielberg's blockbuster classic—a feat of real-world impact never achieved by The Invisible Man, Dracula, or The Creature from The Black Lagoon.

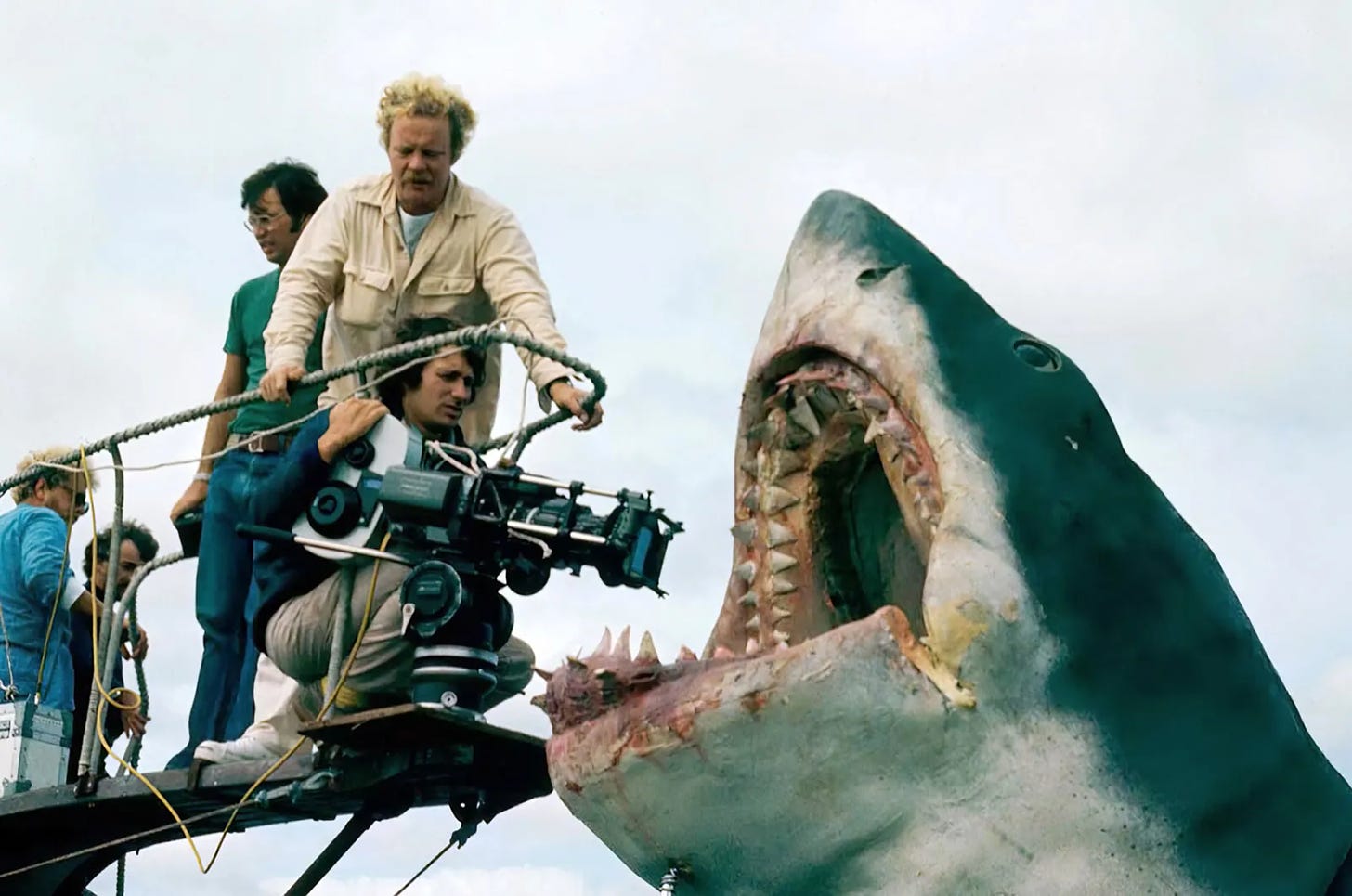

Jaws (1975). Credit: Universal Pictures.

Various aspects of Jaws established long-running tropes in the animal-monster movie subgenre:

The beast's on-screen absence until the third act.

The refusal of government officials to acknowledge the monster's threat to the public.

Shooting on location (in this case, at sea) in the environment where the animal lives.

The deployment of a biologist character to explain the monster's habits and motivations.

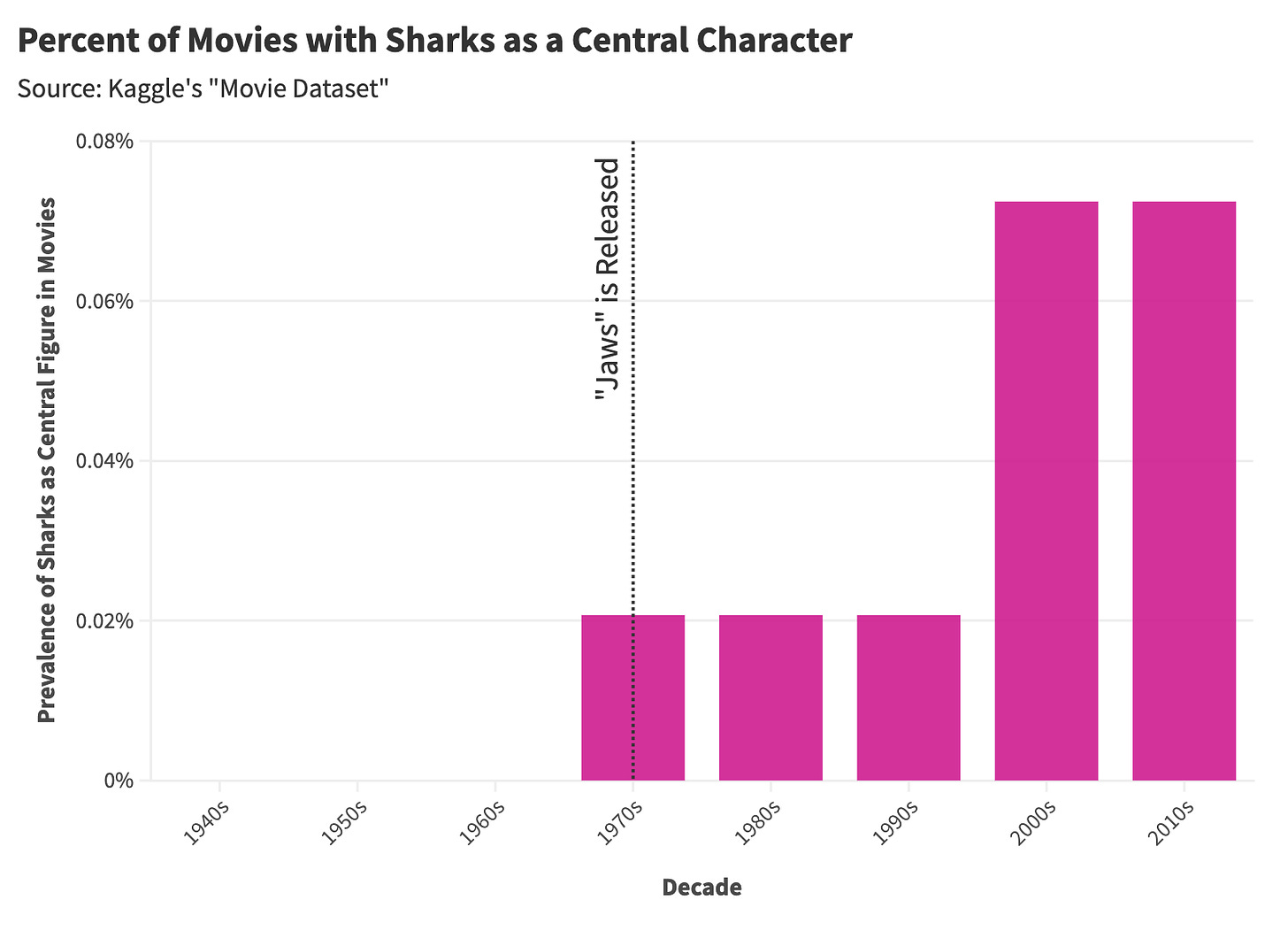

Jaws spawned four sequels and a myriad of imitators like Anaconda, The Meg, Piranha, and Barracuda. Unsurprisingly, there was an increase in the prevalence of shark movies following Jaws' premiere in 1975.

Sharks became a staple of action and horror filmmaking, seldom used in other genres. When was the last time you saw a shark in a comedy, apart from Shark Tale and Finding Nemo (which still portray sharks as menacing)? Animals are often consigned to distinct genres, drawing on the symbolic importance readily attributed to these creatures.

When we look at the genres most heavily associated with a given animal, we find:

Dogs, cats, birds, and penguins are featured in comedies, serving as trusty sidekicks (Turner and Hooch, Tintin) or in anthropomorphized depictions of goofballs (Up!, Garfield).

Lions, tigers, and monkeys frequently appear in adventure movies, likely due to their jungle environment and predatory nature.

Sharks are utilized in action movies, though perhaps it's time we tried something new for a change.

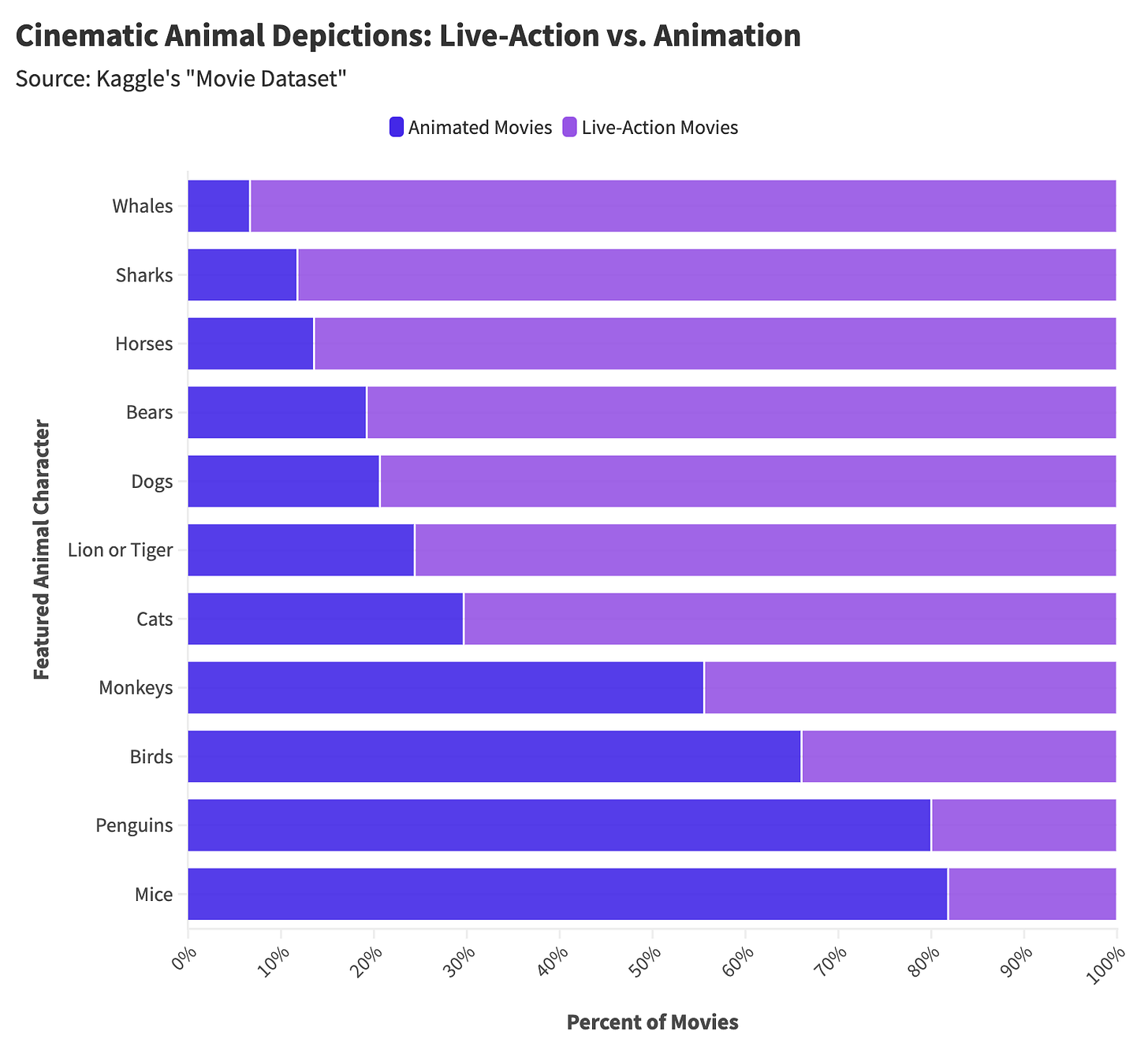

Likewise, certain species predominantly appear in animated films, like monkeys, penguins, and mice, while other creatures are featured in both live-action and animated formats.

It's reductive to say that there are dog films, shark films, and horse films—that you can understand a movie based on its featured creature. At the same time, like any element of narrative construction, such as film score, special effects, and casting, animals can help filmmakers achieve a desired emotion or aesthetic. For example, when we look at the MovieLens user tags associated with horse-centric films, we find keywords related to nobility, war, and Hollywood epics, reflecting the animal's frequent appearances in period dramas, fairy tales, and pre-1920 war movies.

On the other hand, movies with prominent dog characters emphasize the animal's frequent characterization as "man's best friend." Also, both creatures are heavily associated with Steven Spielberg, who apparently utilizes animals often.

It's strange to think of something as uniquely delightful as a dog reduced to a repetitive movie trope. At the same, it's a trope that never gets old—perhaps one of the few. Some Hollywood conventions fade away, like Smell-O-Vision, action heroes walking from explosions, 3D, and young adult vampire fare, but dogs are forever.

Final Thoughts: The Purity of Creature Comforts

Beethoven (1992). Credit: Univeral Pictures.

When I was entering the third grade, my school assigned Where the Red Fern Grows for summer reading. If you haven't read this novel, just know one thing: recommending this story to a young child is an act of emotional terrorism. The book details the relationship between a boy and his two hunting dogs. In the story's final act, one of the dogs is mauled by a mountain lion and dies. Subsequently, the second dog loses the will to live without its partner and dies of despair. It's a devastating read.

I have never cried while reading a book, with the exception of Where the Red Fern Grows. For the first time in my life, I understood the harsh reality of death and the finite nature of existence. Having faced the passing of people in my life, I was familiar with death, but for some reason, this book about two jovial hunting dogs helped me conceptualize mortality. That night, I made my mom sit beside me when I went to bed, terrified by the fate of the hunting hounds from Where the Red Fern Grows.

Flash forward to a few weeks ago when I saw a Finnish film called Fallen Leaves, a deadpan romantic comedy about two loners in Helsinki. Midway through the movie, one of our lonesome protagonists adopts a dog, who quickly becomes the character's faithful companion. The movie's emotional trajectory shifts with this animal's introduction, as we witness the character's spirits uplifted by this newfound companionship. Until this point, I was unsure of my feelings for the film, but as soon as the dog appeared, I became fully invested.

Animals deepen the emotional resonance of a story (or at least, that's my opinion). I'm more likely to identify with a doofus dog (like in Up!) than a hair-brained human. I often cry when an animal dies in a movie, though I do not do the same for every on-screen human death. High-quality monkey-acting or horse-acting amazes in a way that no CGI effect or explosive setpiece can match.

So much of modern cinema is dedicated to spectacle, manufacturing metaverses and far-flung realities. Yet few storytelling elements are as gripping as a well-rendered animal teaching us something about the human experience.

Thanks for reading Stat Significant! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email [email protected]